Natasha works with artisans from Kampung Penambang to make intricate batik (Photo: Zahid Izzani/The Edge Malaysia)

Journalist, editor, author and lecturer, Natasha Mohd Hishamudin is not one to rest on her laurels. When asked why she decided to expand her horizons and become an entrepreneur, she answers, “I’ve always loved batik and have been studying it since my visit to Kuala Terengganu in 2012. I even travelled to Indonesia to study motifs.”

In 2019, she attended a two-week workshop in Kampung Penambang, Kota Bharu, Kelantan, to learn everything she could about batik. She was then the CEO of Gahara, a batik business owned by her friend. “We met those who make this craft and I instantly fell in love with its artistry and community.”

But the determinant that led to her establishing her business was the poverty she had witnessed there. “The more I got to know them, the more I realised that we were at risk of losing our heritage in batik production.”

Urbanisation is one of the reasons the younger generation is not interested in pursuing this craft. “It is a tedious and laborious job, done in humid remote places. The youth prefer to seek opportunities in bigger cities. If we lose our artisans, we will lose our heritage,” says Natasha.

“Indonesian batik was added to Unesco’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list in 2009 and has been internationally recognised, but we were at risk of losing ours. I knew I had to do something about that.”

Natasha set up Retno Dumilah Sari Design — the company’s name is inspired by the main character in the fantasy period film Puteri Gunung Ledang — right before the Covid outbreak. She spent the time during lockdowns researching the market, collecting data and brainstorming the vision for the business, including the prints and silhouettes that would be suitable for local consumers.

In the initial stage, it had not been decided whether the label would sell clothes for men or women. “We were open to both but after looking at the data from our survey, we realised not many brands sell quality, affordable and attractive locally-made batik for men.”

Retno Batik works with artisans from Kampung Penambang and uses the block technique (batik terap) in its production, where copper blocks are carved with patterns, then dipped in wax and stamped onto fabrics. The roles of creating blocks, stamping and colouring are given to different people in the village. “This is a communal craft. By the time you wear the piece, it will have been made by seven people. Indirectly, you have fed several people.

retno.jpg

“That’s what makes Retno different from the rest. We come from a place where we know the craft because we work directly with the community; there’s no middle person. We pay straight to the artisans,” Natasha stresses.

Based on its research, the team found Malaysian men generally prefer to wear cotton, given that the material is most suitable for our weather. Retno uses cotton poplin, which is easy to maintain and provides optimum colour absorption. Some of the brand’s signature styles include transparent buttons, no lining and pockets. Only available in short sleeves for now, the designs are not too loud, with patterns preferred by local men.

Since launching its first batch in December 2021, the label now has seven collections. Retno plans to release a minimum of six per year, depending on the response.

Natasha’s goal has always been to make an impact on society. Another way to do this, besides helming Retno, is through writing. After seeing the chaos brought about by the pandemic, she decided to pen down her thoughts on poor leadership, weak healthcare systems and the frailty of human communication.

The editor of Ellemeno (a literary journal) saw people pouring out their thoughts and feelings on social media and was worried that these words would be forgotten. “I decided to write a book because I wanted it to stand the test of time. I don’t have children and I don’t plan to have any in this lifetime. So for me, this book was me giving birth during lockdown. I wanted it to have my DNA and what I thought about the world at the time,” says Natasha.

She would read headlines and arguments about our country and the rest of the world, and write down what she could in her journal every day without fail. “It was funny because this invisible virus came and everything collapsed. Suddenly, you saw the reality of leadership. We witnessed the poor infrastructure in our country. We had people who couldn’t afford to put food on the table after one lockdown. We denied children 42 weeks of education, which led to 10% of learning loss.”

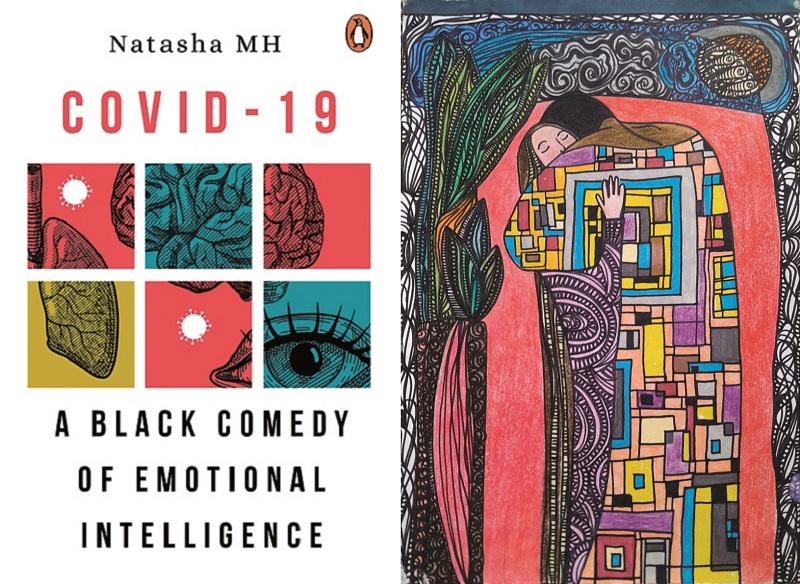

In Covid-19: A Black Comedy of Emotional Intelligence, published in November 2021, Natasha questions how we had allowed ourselves to get to this level of destruction, even with all the structures and organisations in place. “It came to a point where the government had no better solution than to suggest that you eat into your pension fund.”

natasha_2.jpg

Both a social satire and a reflection, the book encourages readers to rethink and question their actions when dealing with crisis. “For me, satire is not about laughing out loud. It’s designed to make people reflect on what they have done.”

Although Natasha was writing continuously, she sometimes felt that words were not enough for her to express herself. During those times, she would pick up some brushes and a canvas or sketchbook, and use colours and lines to convey what was on her mind. Like her book, the topics that fascinate her are far from the light.

For instance, The Holocaust series, which includes Hope of Auschwitz, Lives in Treblinka and Garden, explores the horrors of concentration camps and stories of survival. “When I was reading about the Holocaust survivors, what I admired was their sense of knowing and belief in who was going to make it out of that place and who wasn’t.

“For me, it’s about strength and resilience. My paintings are all about those themes. So they’re not a nightmarish kind of abstract. I saw the strength of the survivors and I was trying to channel that into my artwork.”

Natasha also uses art as therapy, portrayed in her Sketchbook series, which was first completed in 2013. “I went through depression and had a hard time finding words to express myself. While going for therapy, I discovered that when a situation is too tough, you lose the vocabulary because the emotions outweigh the words.”

She was advised by her therapist to “draw anything just to get something out”. And once she started, she could not stop. The walls in her bedroom were filled with different kinds of paintings, which she created using a variety of pens.

“My parents were shocked when they saw those drawings, which also had naked figures, but it was my way of dealing with my vulnerability,” she divulges. In this series, she also drew buildings and structures as she was intrigued by complicated lines.

The 47-year-old has a lot of titles under her belt, but as a lifelong learner (she is currently doing a PhD in organisational behaviour), author, writer and entrepreneur, she wants to keep giving back to the community. “My journey as a literature student, journalist, lecturer and social entrepreneur all has a common denominator, and that is human interest.”

This article first appeared on Mar 6, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.