H&M's 'Close the Loop' denim collection pushes towards sustainable fashion

When was the last time you made a beeline for the recycling bins in a store to drop off unwanted garments instead of the bargain corner? The answer is most probably never. If Confessions of a Shopaholic taught us anything about the joys of shopping, it is that it feels “like waking up and realising it’s the weekend. Everything else is blocked out of your mind; it’s pure, selfish pleasure”. Such retail therapy sounds utterly blissful, provided you are Rebecca Bloomwood who lives in a world with no repercussions.

Fashion waste, exacerbated by a rigorous “fast fashion” system of production, has become an environmental crisis on a global scale. And there are the numbers to prove it. According to Newsweek, 84% of unwanted clothes in the US went into either a landfill or an incinerator. In Australia alone, more than 500,000 tonnes of textile and leather end up in landfills each year, as reported by ABC News. More worryingly, “nearly 1.13 million tonnes of clothes were bought in the UK last year, causing 26 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions from production to disposal”, research by the government’s waste advisory body, Wrap, reveals.

In response, retail giant H&M launched a garment-collecting initiative worldwide in 2013 for people to toss out their unwanted clothes — no matter what brand and condition — at any local H&M store so they can be given a new purpose. Recycling textile is one effective way to make fashion brands less dependent on virgin resources, thus “closing the loop” and achieving a sustainable apparel industry. Problem solved, right? Not so fast.

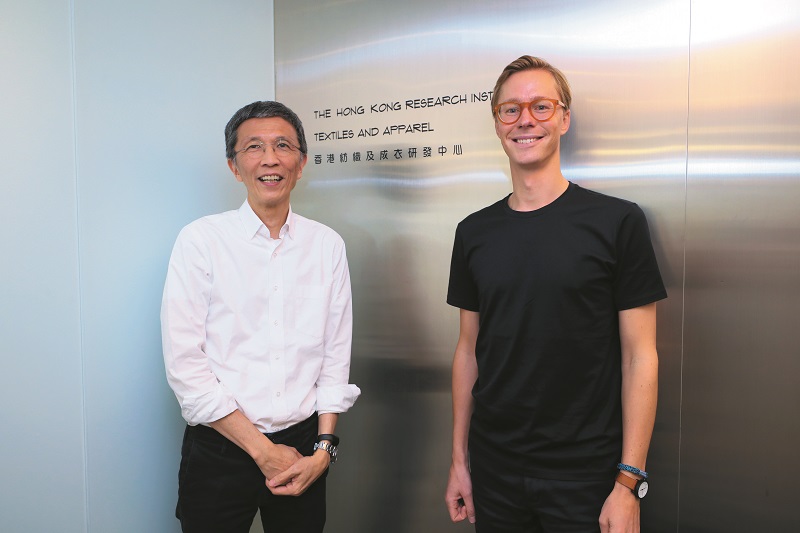

For the longest time, the fashion industry has not been able to properly break down blends such as cotton-polyester, which is essentially non-biodegradable, and turn them into wearable new material. But not all hope is lost. The H&M Foundation, a non-profit independent legal entity operating outside H&M’s value chain with its own staff, strategy and board, teamed up with the Hong Kong Research Institute of Textiles and Apparel (HKRITA) in September last year to recycle blended textiles into new fabrics and yarns.

The global foundation, privately funded by the Stefan Persson family, aims to improve the living conditions of people on an international scale. Championing sustainable fashion is just one of the many laudable causes it advocates, including quality education for every child, worldwide access to clean water and sanitation, and female empowerment so that women in poor communities are equipped with the skills and capital to start their own business.

Hong Kong: The hub of textile recycling

The face of Hong Kong has changed over the years but its famous three Cs — cultural abundance, commercial vigour and char siew bao — have remained steadfastly appealing. As much as Hong Kong is recognised as a food haven, investors identify the world’s fourth largest financial centre (after London, New York and Singapore) foremost as a shopping hub where manufacturers and retailers seek exposure to the flourishing mainland Chinese market. The city’s strategic location and plenitude of logistical infrastructure, from its world-class free port to state-of-the-art telecommunications, is the sole reason global fashion brands have put down roots there.

But, alas, as the retail scene swelled, so did the landfills. In a populous city like Hong Kong, depositing clothing might mean getting onto the sardine can-like MTR or a public bus while lugging a bagful of garments to the stores. It is a lot more enticing to just dispose of old clothes. This throwaway culture — not just in Hong Kong but all over the world — is the result of convenient and fast-paced consumerism that hoodwinks us into buying things not to fulfil our basic needs but to make social statements about our lives. After all, not everyone is aware that it takes around 1,800 gallons of water to grow enough cotton to produce just one pair of regular jeans.

Instilling the benefits of recycling has never been easy but to help people recognise waste as a resource — an economic commodity — is a Herculean task. This probably explains the Hong Kong government’s deep interest in the eco-collaboration between the H&M Foundation and HKRITA, which it funds.

“Hong Kong is so invested in textile recycling because it’s a small, densely populated city that is generating a lot of waste. It is ahead of us (in Sweden) in dealing and living with wastage. It’s now turning itself into a strategic hub and leader in this recycling technology because the city also needs to deal with its own problems,” says Erik Bang, project manager of the H&M Foundation.

HKRITA, a publicly funded applied research centre established in 2006, is one of five such centres sponsored by the Innovation and Technology Fund (ITF) of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. The H&M Foundation had the option of working with other research institutions but HKRITA’s track record of working with foreign institutions and its tenacity to offer a quick solution to the marketplace won the foundation over. The latter will pump €5.8 million into the four-year project, which is estimated to cost around €30 million, making it one of the most exhaustive efforts ever in textile recycling.

In a populous city like Hong Kong, depositing clothing might mean getting onto the sardine can-like MTR or a public bus while lugging a bagful of garments to the stores

Edwin Keh, CEO of HKRITA, concurs. “One of the fundamental visions of HKRITA is to have an impact, but you can only create significant impact at a scale — and H&M has that scale. We’re also an investor, if you will. We put resources behind a problem and look for people who know more about the issue at hand to help us solve it. What we’re doing here … you won’t find the next Einstein or the next Nobel Prize winner because we don’t do fundamental research; we do very applied, practical realistic research,” he says.

The organisational brilliance behind HKRITA is that it is not just a research institute but also an open research platform that pools resources and talents from around the world. Case in point: One year into its partnership with the H&M Foundation, HKRITA had successfully developed a hydrothermal (chemical) process to fully separate and recycle cotton and polyester blends with the help of researchers from the prestigious Ehime University and Shinshu University in Japan.

“Recycling is a multi-level problem. It’s a worldwide problem. [If a solution is found] everybody wins, everybody gets to learn,” Keh asserts.

Promising results

At the moment, mechanical recycling — which involves chopping up old clothes to be turned into raw materials — of natural fibres such as cotton and wool is the most scalable technology. But this energy-consuming technique degrades the cotton’s quality in the process, thus shortening the staple length of fibres, which determines the strength and softness of cotton threads. Moreover, this method does not solve the biggest challenge in recycling: separating blended fibre materials effectively.

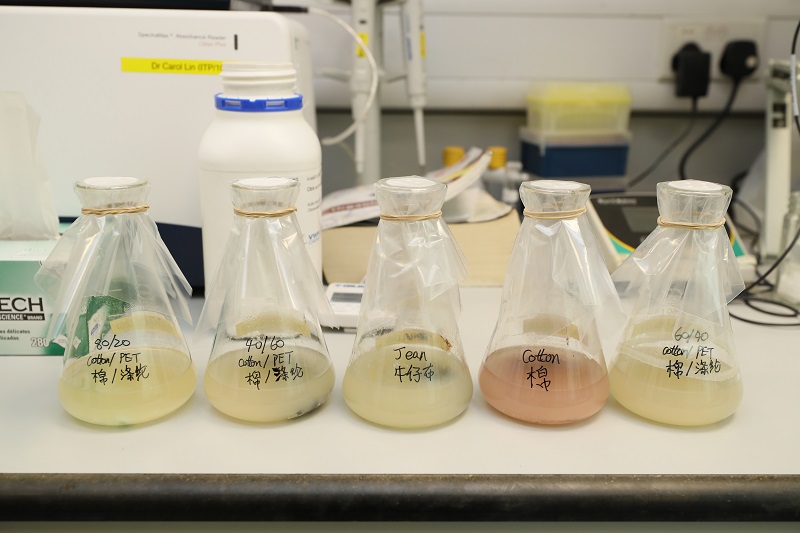

This predicament led HKRITA to focus its efforts on two other methods of recycling: chemical, which uses ionic fluid as well as the hydrothermal approach, and biological, a much greener procedure that utilises micro-organisms and enzymes to break down blends. The novel approach of biological recycling also recovers glucose with over 70% yield from textile wastes, which can be used to produce biodegradable products such as biosurfactant (for cleaning agents) and bio-based polymers.

The relationship between fashion and the environment has always been strained by the harmful ramifications of pollution but can textile recycling truly mitigate the issue? Bang remarks, “We don’t want to create new problems with this recycling technology. People immediately associate chemicals with something bad but the chemical we use in the hydrothermal process is biodegradable and does not cause any secondary pollution to the environment. This fibre-to-fibre recycling process is less energy-consuming and we’re trying to use the least amount of energy possible.”

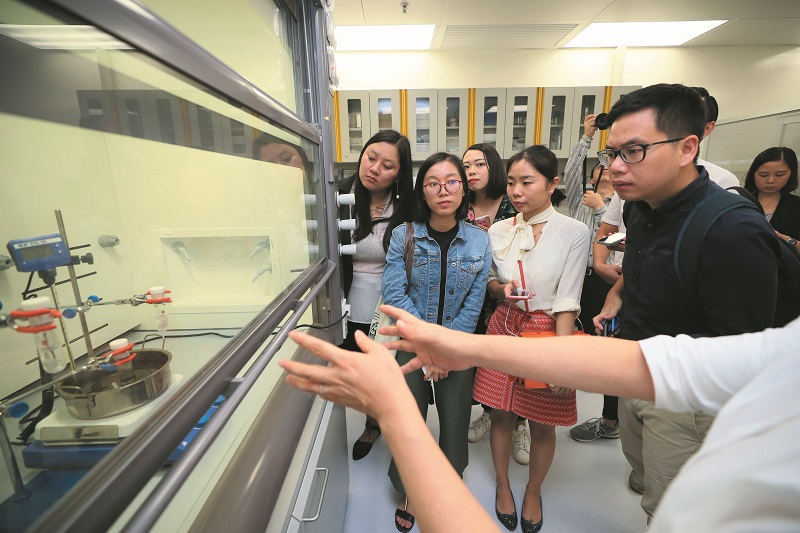

To give us an idea of the recycling technology, we were taken on a tour of HKRITA’s chemical and biological textile treatment laboratories at the Hong Kong Science Park in Pak Shek Kok, New Territories. Inside, researchers in lab coats spoke in near whispers but their voices took on a formal instructional cadence as they described to us the hydrothermal and fermentation processes to separate cotton from polyester. “The latter is like making beer,” one of the researchers said. As Bang and Keh claim, only minimal energy is used to power the machines, such as heating the water in a hydrothermal treatment. In fact, in a biological process, no additional energy is needed because the enzymes are doing all the work.

Future of sustainable fashion

HKRITA’s research progress, while groundbreaking, is currently limited to lab-scale solutions. Naturally, the goal over the next few years would be to roll out the textile recycling technology on an industrial scale to prove its commercial viability. Here is the good news — the outcome of the technology, when finalised, will be licensed widely, including to H&M’s competitors, so that all communities can benefit from it.

Keh is confident that Hong Kong is the right place to spearhead and promote this technological breakthrough. “Hong Kong is still the nexus where a lot of industries meet, so you have manufacturers, yarn suppliers, wholesalers, retailers and brands — all in one place. The whole retail supply chain is right here and that really helps in finding solutions quickly. There are a lot of things out there in the wild [that are designed] with no consideration for recyclability. So, hopefully, 10 years from now, all of us might be making our apparel much more sustainably.”

The concept of “zero fashion waste” has not made much headway with fashion brands so far because while sustainable design does not necessarily mean expensive, overhauling hundreds of clothing factories to employ new technology could cost an exorbitant amount. This also explains why the H&M Foundation is pushing for radical change through its other initiative, the Global Change Award, which attempts to accelerate the shift from a linear to a circular fashion industry. The award, judged by an expert panel that includes Keh, will offer five winners a shared €1 million grant and a one-year innovation accelerator programme to speed up the development of their innovations.

Now in its third year, the Global Change Award has awarded previous innovations such as making leather from wine-making leftovers, weaving digital threads into garments to ease the recycling process, extracting and using cellulose in cow manure to create textile and utilising pre-loved denim to colour new denim. The awardees can give back to the fashion industry with no strings attached because neither the H&M Foundation nor the H&M group take any equity or intellectual property rights in the innovations.

“Green fashion” should not be treated as hogwash anymore because we cannot afford to run on a linear route on a finite earth. In order to feed a growing population’s appetite for consumption, the probable solution is to recycle, and put less emphasis on volume and more on value. So, let your clothes hang on to their hangers a little longer — style may last forever but not the planet.

For more information on the technology breakthrough and collaboration, visit H&M Group.