This life-sized bronze statue of Hemingway was created by Cuban artist Jose Villa, and is found in El Floridita, in Havana, Cuba.

Approximately 15km from my home in Chicago, Illinois, is the Ernest Hemingway’s Birthplace Museum, where this Nobel Laureate was born on July 21, 1899.

In this leafy upscale suburb, flanked by homes designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright, this stately Queen Anne building with a turret and wraparound porch has been lovingly restored. Visitors are ushered into the parlour, which has been recreated from photographs left by Dr Hemingway, Ernest’s father, and the descriptions left in the writing of Ernest’s sister, Marcelline. The rose on the cornices matches the wallpaper exactly, and dappled sunlight falls on a writing desk, cluttered with books from that era.

Hemingway’s formative years were spent within the arms of a family that embraced new technology as well as godliness; his physician father had one of the first three telephones connected in Oak Park. The home was wired for lights even before electric power was introduced into Chicago homes, so the lights in this home allow for gas lighting (with valves) that face upwards, as well as electric lights, which face downwards.

Hemingway was born in a second-floor bedroom of this home of his maternal grandparents, and spent the early years of his life with his Grandfather Abba, teller of tales and hater of war. His father, Dr Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, was a physician and presided over the births of all his six children. Ernest’s mother, Grace, was a remarkable woman. Despite the constraints of her time, she had moved to New York to pursue a musical career and was a well-respected artiste who out-earned her husband.

ernest_hemingway_birthplace_museum_credit_the_ernest_hemingway_foundation_of_oak_park.jpg

This was a home filled with music and books and light streaming through the ancient trees. Years later, Dr Hemingway would commit suicide with a shotgun, and Ernest would end his own life at the age of 61 in a similar manner. Ernest would lose two of his siblings to suicide, and his son, Gregory, would be found dead in 2001 as a transsexual named Gloria, under very suspicious circumstances.

Hemingway would marry four times, and write sparse prose on war and bullfighting which Virginia Woolf described as “self-consciously virile”. He would build a cult of performative masculinity that writers like me find virulently misogynistic.

Yet this house — Ernest’s home until he was six years of age — frames the image of a gentle boy, his crib placed close enough to his sister Marcelline’s, so they could hold hands through the bars at night.

There is also this picture: Ernest, as a one-year-old, is dressed like a girl, in frilly lace.

This in itself was a fashion of the times, but Ernest’s mother was also inexplicably determined to present her two eldest children as twin girls. Ernest, younger than Marcelline by 18 months, was dressed as a girl until he was at least five years old; Marcelline was held back in school by their mother so that the impression of twinhood could persist.

It is a matter of speculation of course, how much of Ernest’s later hyper-masculinity was a rebellion against his mother, whom he hated and blamed for his father’s suicide.

hemingway.jpg

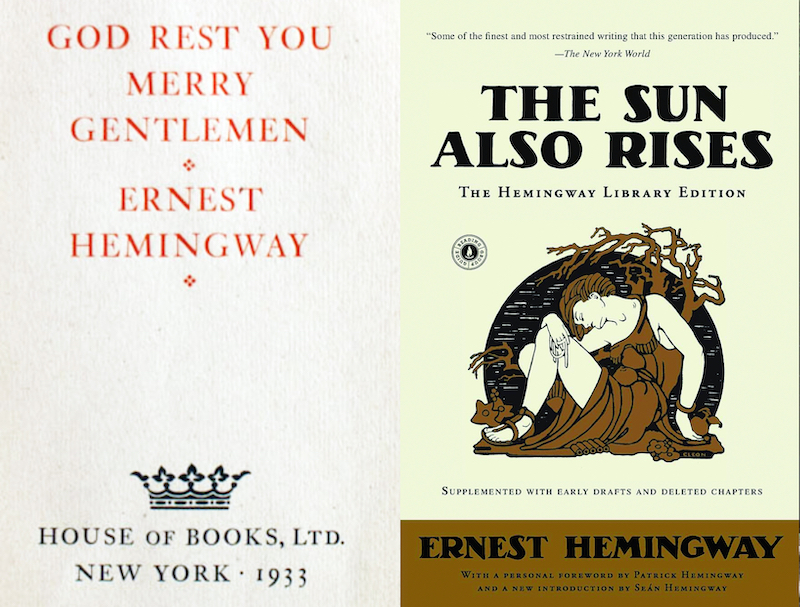

Themes of women and death would recur in his books. Emasculation is also notable in Hemingway’s work, God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen and The Sun Also Rises. Hemingway would label his writing style the iceberg theory, a spare and lean narrative prose that relied on the theory of omission, and was in sharp contrast to the more flowery literary English of the times.

In his work, love was the conflict, as in this extract from A Farewell to Arms:

“Maybe...you’ll fall in love with me all over again.”

“Hell,” I said, “I love you enough now. What do you want to do? Ruin me?”

“Yes. I want to ruin you.”

“Good,” I said. “That’s what I want too.”

There is no doubt that he changed the nature of American writing, and moulded the language of the short story. He brought a sense of peripatetic travel (used bilingual puns and codeswitched sentences), and nurtured a braggadocio and machismo seen as misogynistic and homophobic and racist.

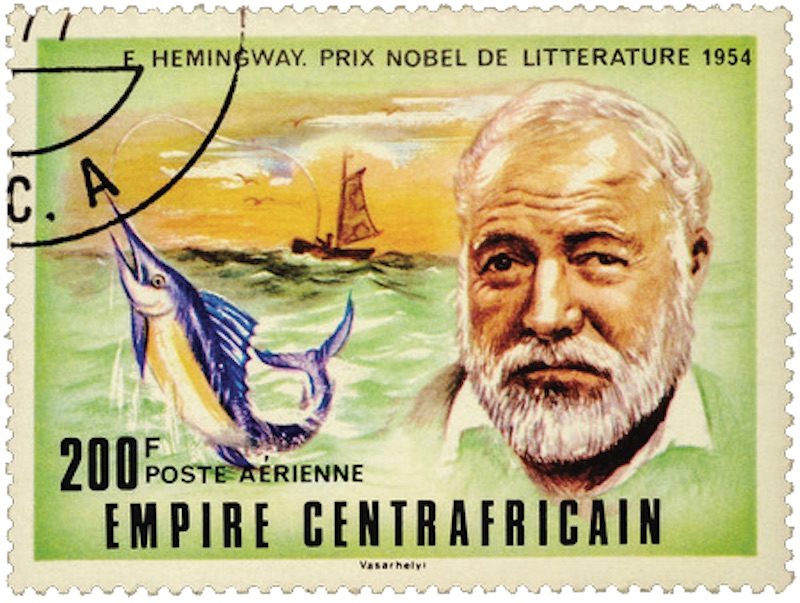

ernest hemingway stamp.jpg

Hills Like White Elephants is a short story by Ernest Hemingway, first published in August 1927. It is a masterclass in dialogue-writing, and I have used it with students in Kuala Lumpur and Chicago and New Delhi and Amsterdam, for the terse prose cuts across global lines. The tension is knife-edged, although the central conflict is not named. It is a brilliant piece of writing, widely anthologised.

This home in Oak Park, filled with family memorabilia and photographs, is a poignant reminder of the early years of Hemingway. He was born into an elite family that revered learning and words and painting and music and modern gadgets, but also a pervasive sadness.

“You can’t get away from yourself by moving from one place to another,” he wrote, in The Sun Also Rises.

In the library, a pair of owls peek at the visitors from below the books.Dr Hemingway (also an accomplished taxidermist) shot the pair of birds dead during his honeymoon — their nightly hooting was too noisy — and stuffed them as a gift for his bride. The owls perch there, an enduring legacy, even after death.

The world’s a moveable feast

Still stricken by literary wanderlust? Daydream a little using these internationally sourced ideas, courtesy of Papa Hemingway himself.

Compiled by Diana Khoo

Eat

If you loved The Sun Also Rises, chances are you may remember its ending, where Jake Barnes and Lady Brett Ashley reunite in Spain’s capital city to eat roast suckling pig — the speciality of El Sobrino de Botin, acknowledged as one of the oldest restaurants, if not the oldest, in the world — accompanied by glasses of Rioja Alta. Adding to the romance and history is the rumour that artist Francisco de Goya once worked here as a young man. Established in 1725, Botin is famous for rustic Castilian cuisine. If the idea of a whole roasted porkling does not appeal, opt instead for hearty, indulgent dishes such as squid cooked in its ink, garlic soup and the famous cream-filled Tarta Botin cake.

Calle de Cuchilleros, 17, 28005 Madrid, Spain.

Drink

Drinking came as easily to the great novelist as words did. From Paris to Lima, Hemingway loved to imbibe. Daiquiris are the cocktails that have come to be inextricably linked to the Hemingway mystique and it was said that he often ordered double shots of the drink, leading them to be known as Papa Dobles. Although association with the author has made several bars famous, from Harry’s Bar in Venice to Sloppy Joe’s in Florida’s Key West, it is El Floridita in Havana, Cuba, that is reputed to be the birthplace of the Papa Doble, essentially a daiquiri but with less sugar and more rum.

Obispo 557, Esq A Montserrat, Habana Vieja, Cuba.

Stay

Paris’ Left Bank has long been associated with the literary world. And with good reason. Sylvia Beach’s famous bookstore Shakespeare & Company may be found here and historically and culturally significant figures who have lived and written in or about the Rive Gauche are numerous. The place to stay is undoubtedly the 111-year-old Hotel Lutetia, which reopened to the public in 2018 after an extensive but sensitive four-year renovation under the eye of architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte. James Joyce wrote Ulysses at the hotel with Hemingway acting as occasional editor, in between drinks at the bar with Gertrude Stein.

45 Boulevard Raspail, Paris, France.

This article first appeared on Jul 5, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.