The historic Badshahi Mosque, built during the reign of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site (All photos: Lee Yu Kit)

Small sparrows flutter against the mesh of the net holding them prisoner. The man who holds the net offers a special price to a foreigner to set three, instead of two, sparrows free for PKR100 (RM3). Released, the birds soar high overhead, into the sky of Lahore’s Old City, a labyrinthine warren of over 4,000 alleys and home to half a million people, a walled city within Lahore, the capital of Pakistan’s Punjab state.

The site of Lahore has been continuously occupied since ancient times, but it rose to its apogee during the 16th to 18th-century rule of the Mughals, whose lavish lifestyles and staggering wealth would make modern-day millionaires gnash their teeth in envy. Lahore became their capital, and their legacy endows Lahore with grace and the lingering scent of grandeur. Although the Mughals were succeeded by various rulers, notably the Sikhs and the British, their imprimatur continues to define the city.

A cacophony of noises, sights and smells assails me on the narrow streets of the Old City: bicycles, motorcycles, cars, donkey carts, all following their own rules and pace. Motorcycles are parked haphazardly, cars stop without warning and pedestrians step out into oncoming traffic with blithe indifference. Here are crowds milling around a stall selling stewed free-range chicken with bread, freshly made in the tandoor oven just a few shops away, with the baker plastering discs of flattened dough to the insides of the oven and removing them with metal hooks.

Over there, a man scoops out cool almond curd into bowls, while next door, an electric fan provides ventilation for cooks, their hair in shower caps, scooping out blistered, hot puri from a vat of hot oil. Down a side alley, kernels of corn are being fried in a pan of salt. In a doorway, a man sits before a large vat of bone broth, with big bony pieces lining the sides of the vat. And always, there is chai, the ubiquitous milk tea, thick, steaming hot, irresistible, scooped out of large pots kept constantly on the boil.

There is industry and temptation everywhere. Small shops are stacked to the ceilings with goods, men loll outside shops with shiny pots and pans and showers of sparks fly from the grinding wheels of knife smiths sharpening blades for Muharram, the period when Shi’ite Muslims flay themselves with blades swung on chains, mourning in self-flagellation the death of Hussein, grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, in 680AD.

For lunch, I eat at a small restaurant with no signboard, but it is popular with the locals. It incorporates a bakery for hot-from-the-tandoor bread, with big vats of ready-cooked food, which include chicken biryani, curries and stewed and chopped spinach and turnip. Separately, a cook makes special-order dishes, such as mutton or chicken karahi, simmering away in karahi pots.

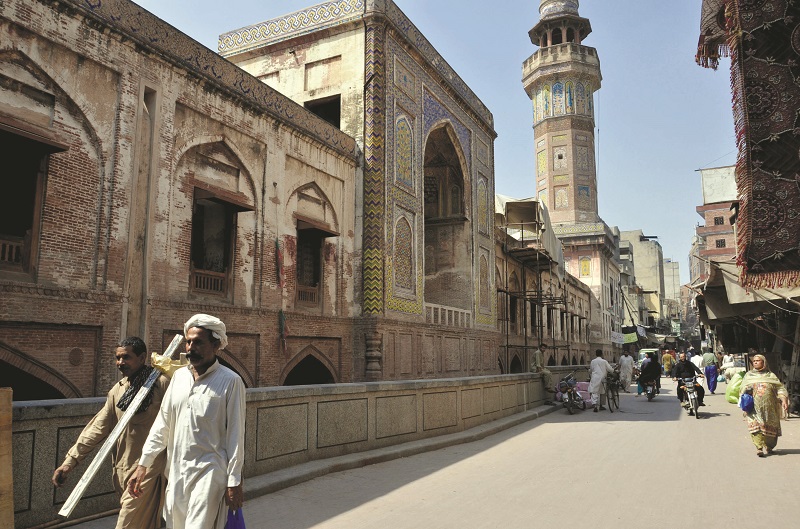

Amidst this hubbub of activity are oases of stillness. The Sunehri Mosque, called the Golden Mosque for the coppery glint of its onion-shaped domes, was built towards the end of Mughal rule. It is symbolically raised above the plebian pursuit of commerce on an elevated platform. Simple in form and relatively unadorned, it contrasts with the splendour of the much larger, ornate Mughal-era Wazir Khan Mosque, located near the Delhi Gate, one of the original gates of the Old City.

Even with the ravages of neglect and time, the mosque is magnificent, with its proud design and elaborate embellishments showcasing the highlights of Mughal architecture. It stands near another Mughal landmark, the Shahi Hammam Persian-style baths, built during the reign of Shah Jahan, of Taj Mahal fame.

But the faded grandeur of these monuments is just an appetiser, as I make my way out of the Old City, braving the haphazard traffic, into greater Lahore and its cultural heart.

The modern city of Lahore is surprisingly green, with mature trees lining many of the major roads. Vertical gardens cling to the concrete pillars supporting the elevated Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, for Lahore is a city of contrasts — modernising, yet held in thrall to its historic splendour.

The British left their mark on the city as well, most evidently in the names of many roads and places, signs in English rather than Urdu, the national language, in the infrastructure of railroads and the administrative machinery of schools and government, in popular culture with cricket-mad Pakistanis and the quaint accommodation to local culture resulting in that curious, antique blend that characterises the British Raj of the late 19th century.

Only taken as a whole do I appreciate the influence the Mughals had over the city during their heyday. The heart of Mughal culture is the Lahore Fort and the Badshahi Mosque, located next to each other, a little distance away from the Old City. I found the mouldering Lahore Fort to be a little sad, in the way of faded splendour and magnificence, like a dream fantasy re-examined in the cold light of day.

The great Mughal Emperors — Babur, Akbar, Shah Jahan, Jehangir, Aurangzeb — ruled their far-flung domain from these pavilions, with their vast spaces, magnificently adorned marble buildings, spacious gardens, ingenious engineering and graceful proportions. Water played an important role in Mughal architecture, both for cooling as well as for aesthetics, and elaborate marble screens speak of finesse and exquisite taste.

Each of the emperors left a legacy behind. They lived in grand style with hundreds of servants, musicians, entertainers, courtesans, advisers and the whole machinery of an elaborate royal court, which existed for the pleasure of the emperor. Behind the inscrutable walls of the fort, were stunning masterpieces, one such being the Sheesh Mahal, which was built during the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan.

Around a broad open courtyard with fountains, white marble buildings with delicate carvings are inlaid with precious stones, the surfaces of the inner building covered in small mirrors, so a light held up reflects as a constellation of shimmering stars.

The Naulakha Pavilion, an engineering marvel with its elaborately arched roof of marble, exudes feminine grace, providing a hint of the pleasures of the Sheesh Mahal to the emperor.

But it was not all play, for the Emperors wielded enormous power, as in the Diwan-E-Am, the Public Audience Hall, where Emperor Shah Jahan held court and presided over gatherings of ordinary citizens who sought a royal judgement or wanted to make an appeal.

In contrast to the extravagant luxury within, from the outside, Lahore Fort projects muscular power, from the massive, iconic Alamgiri Gates to the broad, shallow Elephant staircase, trodden by bejewelled elephants carrying royals, riding distantly above the crowd in silken palanquins. There are only faded shadows of distant splendour, yet I could almost imagine what it could have been like, the pageantry, the noise, the colour and the adulation that once rang through these empty corridors.

In contrast, the neighbouring Badshahi Mosque, built during the reign of Emperor Aurangzeb in the 17th century, continues in use to this day, a dazzling structure of graceful proportions and symmetrical architecture. Red sandstone transported from Jaipur, in present-day India, imparts the distinct rose tint of the mosque. Bulbous onion domes and tall minarets catch the eye, as does the delicate tracery on the wall panels. Architectural precision abounds in the details. Minarets are angled slightly outwards to avoid damage to the mosque in case they topple during an earthquake.

The mosque is aligned to perfectly frame the Alamgiri Gates of the Lahore Fort. Doorways in the side corridors are lined with astonishing precision, and the acoustics of the mosque, built when there were no electric loudspeakers, continues to confound today.

We know what the Mughal idea of Paradise was: manicured, landscaped gardens of exotic trees and plants with fountains, waterways and marble pavilions, painstakingly decorated and symmetrically laid out. We know this because of Shalamar Gardens, 16ha of terraced gardens, a few kilometres from the walled city.

Water flowed in long shallow canals, spouted from fountains, rippled over a hand-carved marble screen into broad, shallow pools and gushed from artificial waterfalls which, backlit with candles, shimmered with an artificial rainbow. There were separate sections for royalty and the public, which, even now, evoke an atmosphere of peace and calm, away from the grit and grime of Lahore.

On my last night in the city, I arrange for dinner at Cooco’s Den, a local institution on Lahore’s trendy Food Street, with centuries-old mansions, or havelis, restored and turned into stylish restaurants. Cooco’s was the first to feature rooftop dining, its signature moment being when I step onto the cool roof terrace, with tables arranged under the stars. It overlooks the Badshahi Mosque, its domes and minarets softened by backlighting.

I dine with the magnificent mosque on one side, a Sikh gurdwara a little distance away on the other, in the neighbourhood of Lahore’s traditional red-light district. The sounds and lights of the city seem distant, in this dream-like place, surrounded by splendour, on a rooftop above Lahore.

This article first appeared on May 13, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.