The main point of interest in the village is the dwellings carved into the volcanic rock mounds. (Photos: Lee Yu Kit)

This is an ancient part of the world. It is dry and dusty and barren in places, and I know its antiquity when we stop along the road under an insolent blue sky. There are burrows and holes in the ground. These were dwellings and people lived in them centuries ago. We don’t know much about them but I try to imagine people living, stooped in the low confines of the tunnels with their separate rooms. It must have been warm and safe here when it was cold and dangerous outside. The burrows are quite spacious. Looking out from them, you can see the open sky though a hole in the long doorways.

A little further on, the road opens out and there is Kandovan village, but it looks like something from a novel written by a fevered author. This is not a normal village. The hills are pointed cones of rock and the village is in them, spread out across my field of vision — people living in rock dwellings. Legend has it that these people were fleeing from invaders and sought refuge here, in this valley of volcanic rocks, but archaeology proves that these dwellings have been inhabited since much earlier times, for millennia before.

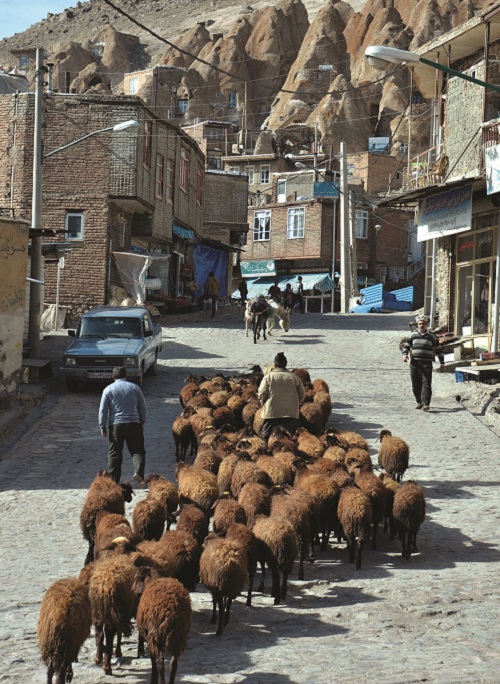

We drive into the village. There are regular wooden and brick shops along the road while behind them rises the strange village. There are walkways and staircases threading their way between the rock houses. Some of them have been converted into hotels for the sheer experience of living in a rock village — one of very few in the world. This is a living hamlet with people inhabiting these rock houses, laundry hung out to dry, kitchen doors open, chickens foraging in the yards, children playing at the landing at the top of a series of steps.

My guide leads us to an open house and we peer in, at the comfortable interior carved out from the soft volcanic rock. We see linoleum flooring, wooden furniture and carpeting. It is cool inside. There is electricity and running water, obviously installed relatively recently. The volcanic rock provides natural insulation, keeping the houses warm in the winter and cool in the summer.

There is a separate enclosure, a little further down, for the animals. Everyone climbs up and walks down steep flights of steps because the village is more vertical than it is horizontal. Hotel rooms are equipped with Jacuzzis, hot and cold water and all the comforts of home, and there are restaurants, where you can have a cup of tea out on the terrace, looking down at the rock houses below.

Kandovan is also famous for handicraft, notably hand-woven silk scarves, and for its agricultural produce. I buy nuts, figs and honey from a small shop by the main road, watching the golden treacle fill a small jar. The honey is from a mountain meadow and it tastes wonderful — thick, dark-coloured, smooth and not too sweet.

The antiquity of Kandovan and the burrow houses is confirmed the next day at the Azerbaijan Museum in Tabriz, an hour’s drive away. In the long, large halls of the airy building are stone carvings and ancient artifacts that bear witness to the long history of this place, ancient civilisations with their languages, script and the influences of foreign cultures, for Tabriz was on a trade route between the East and the West, between Europe and the eastern lands. Ancient though Persia is, even more ancient civilisations once thrived here.

A short walk from the museum is the Blue Mosque, one of the most significant buildings of its time when it was built in the 15th century. Renowned for its beauty, it was severely damaged in an earthquake in 1704. Large-scale restoration is underway but it is a daunting task. I stand inside the Blue Mosque, my head thrown back to take in the scale of the building. Light filters through the windows set high above. Though damaged, it is heart-achingly beautiful, its immense size giving it the quality of soaring magnificence. The proportions, the details of high vaulting arches, intersecting ribs, an immense doorway, all contribute to its overall grace.

Tiles of delicate lapis lazuli blue, bands of Quranic inscription and turquoise cling to some of the walls with filigree edging on door panels. The Blue Mosque in Esfahan provides a reference to how strikingly beautiful this mosque must have been at one time.

Tabriz was once an important trading town on the Silk Road, where traders and merchants from opposite sides of the world met and mingled. The city is still bustling with activity and commerce, and I find the warm-hearted, good-natured friendliness I have encountered almost everywhere in Iran. Strangers stop on the street to enquire where I come from and offer a welcome, families invite me to share their afternoon meal and teenagers are unabashedly curious, following a visitor with the kind of curiosity that would seem suspicious in many other parts of the world.

At night, the streets are alive with people going about their business, the roads dense with traffic and the restaurants busy. Tabriz straddles the modern and ancient worlds with modern hotels and ancient quarters, a living, breathing testament to history and the evolution of civilisation. I reflect on the vast gulf of understanding there is between the Iran of the popular imagination and the reality on the streets.

Inexorably, I am drawn to the nexus of the city, the great and sprawling Bazaar of Tabriz. Bazaars are thriving communities in Iran, places for commerce, for everyday shopping, meeting places, supermarkets, department stores and community spaces all rolled into one. The Bazaar of Tabriz is the oldest in the Middle East, the largest covered one in the world and recognised as a Unesco World Heritage Site. It is a place not only of human activity, but also of great beauty, culture and history.

A trading place since antiquity, the Bazaar of Tabriz was already famous in the 13th century. For centuries, it was one of the most important trading places in the world. It was a vast melting pot of many influences from far-flung places, where exotic goods were traded, a complex and diverse place where ideas that built and tumbled entire societies were exchanged.

Exploring this enclosed marketplace is an adventure in itself. It is subdivided into multiple sections, connected by a vast network of brick walkways beneath the running domed arches penetrated by windows and sunlight. The brickwork in many places is of such striking symmetry and beauty that it is a work of art in its own right.

There are modern appliances and electronics crammed into small shops, and shops where bolts of cloth climb to the ceiling with gaudy fabrics rustling from the shopfront. There are stores where shafts of sunlight illuminate thick carpets rich with traditional motifs and modern scenes, handicraft stops that glisten with glass and filigree brasswork, narrow shopfronts colourful with nuts and dried fruit, fragrant with spices. Ornate gold and silver shops stand in contrast to traditional blacksmiths and tailors with glitzy suits on mannequins. There are restaurants of relative quiet where one can have a meal of sizzling kebabs or steaming hot khoresh stew.

I find a traditional tea stall and settle down in a corner of a large, open, roofed space called a timcheh, soaking in the sounds, smells and sights of the bazaar around me. The outside world seems distant and irrelevant here in my corner in an ancient bazaar where the pace of life follows age-old rhythms. It was already old when the Blue Mosque was built. Produce and handicraft from the volcanic-stone village of Kandovan continue to be traded here. The ancient peoples whose artifacts populate the Azerbaijan Museum exchanged goods and services in the place where this bazaar now stands.

Sipping hot tea in this magical place of light and suspended time, I am content. Let the world wait.

This article first appeared on Feb 26, 2018 in The Edge Malaysia.