The Penang Hill Railway launched its service on Oct 21, 1923 (All photos: David S T Loh)

Between the sea and hills that have put Penang on the tourist map lies a metal track that, with some imagination, could be viewed as the backbone connecting both attractions. It starts from the base station at Jalan Bukit Bendera, Air Itam, and winds up to the Upper Station on Strawberry Hill, the jump-off point to discovery and experience.

The Penang Hill funicular railway is as fascinating as the city it gazes out onto. Its history, anchored to the arrival of Francis Light in 1786, encompasses meeting the recreational needs of British officers, engineering feats that drive three generations of rail service, and being a vehicle that contributes to the growth of the township at the foothills.

A century after launching its service on Oct 21, 1923, Penang Hill Railway is celebrating “100 Years of Transformation”, the subtitle of a book that captures pivotal events, projects, challenges and milestones along the journey. Counting down to a gala dinner to mark the centenary on the same date this month, Datuk Cheok Lay Leng, general manager of Penang Hill Corporation (PHC), recaps the rail story.

“We hope people will appreciate that the funicular system, now in its third generation, is not just a tourism product. It plays a significant role in socio-economic development in and around Penang Hill. It created jobs and helped businesses in the vicinity, which used to be coconut plantations. That’s worth celebrating.”

cheok_wearing_cap.jpg

Penang Hill, the first hill station in Southeast Asia, was established in 1788. The cooler clime made it ideal for convalescence, relaxation and escape from the heat and disease in the lowlands. It also has military significance: With six peaks, the highest reaching 833m above sea level, it was a vantage point from which to look out for approaching vessels in the Strait.

“British SOP overseas was to set up hill stations wherever they went or in the countries they colonised. Hence, the many stations around the world,” Cheok adds.

Market demand influenced the idea of creating the hill railway on the island. Studies were carried out from 1897 but a project initiated in 1905 using a Pelton water wheel instead of a steam engine failed. Next, Arnold Robert Johnson, the Federated Malay States’ resident engineer for railway systems, was assigned to design a funicular system for Penang Hill. He visited Hong Kong, where one had begun operations in 1888, came back and produced “an engineering marvel”.

Funicular systems are not identical as each is custom-made based on the geological structure of the local terrain, Cheok explains. Penang Hill’s system follows the slope and features a tunnel. “At that time, the Penang Hill tunnel was among the steepest, if not the steepest, in the world.”

One of the things PHC aims to do is register Penang Hill Railway as a state heritage. The corporation’s roles include operating the funicular system and taking charge of infrastructure on the hill, which also covers developmental controls and policies. Special area plans ensure development is sustainable and the place can be a catalyst for socio-economic development by asking: Will the projects benefit the hills?

a_european_lady_being_carried_on_the_sedan-chair_by_doolie-carriers_circa_1895.jpg

Over the last 100 years, the funicular service has transported more than 48 million passengers, from colonial civil servants to residents, workers and tourists. “Our responsibility is to find ways to enhance its reliability and extend its lifespan so we can continue to serve for the next 100 years.”

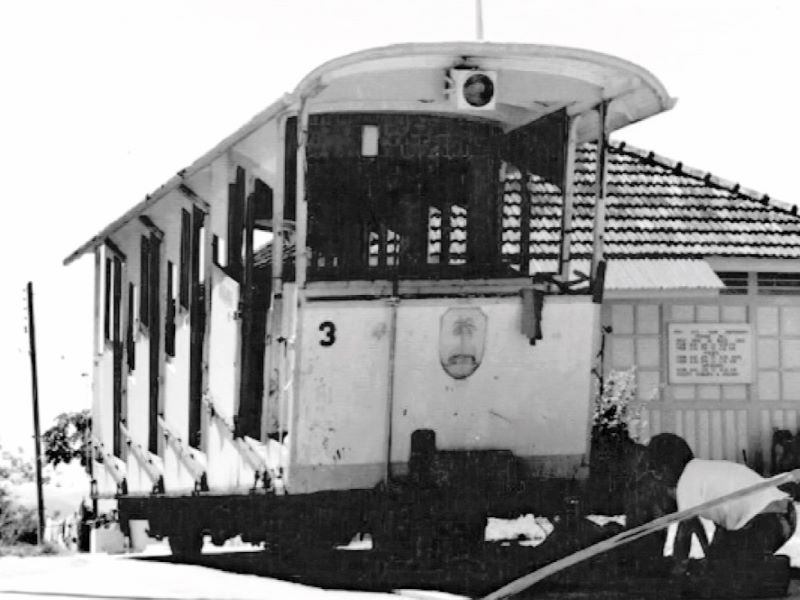

Between 1923 and 1977, the railway took about 12 million people up and down the hill in its first-generation wooden coaches. These were replaced with Swiss-made red-and-white carriages with fans and automatic doors that served the same number of riders for 33 years until 2010. Capacity had increased and service was more reliable but the ride from the base station to the summit took 30 to 40 minutes, and people still had to alight halfway to change trains.

An overhaul was in order. Engineers re-routed the railway, bypassing the Middle Station, and in April 2011, the third-generation funicular system rolled out with two coaches named Pinang and Mutiara, each with a capacity of 100 passengers. The ride from the bottom to the top stations, non-stop, takes only five minutes!

“We encourage people to take [advantage of] this service because it is fast and safe. It’s popular because it’s heritage. You’re not just going up to the hill; you’re going through 100 years of the railway’s journey,” says Cheok.

the_first-generation_train.jpg

What is unique about Penang Hill? The scenery, tranquillity, fresh air and panoramic views, he posits. People also go for a nice meal. “We’ve had requests to bring back the old Hainanese chicken pie!”

It’s a place where family and friends bond over healthy activities and many head up in big groups. He has seen a significant increase in hikers — easily 400 to 500 on weekdays and about 1,000 come weekends — who pant up together, then head straight for ice kacang at Astaka, the three-storey F&B centre that serves local favourites, with a view.

PHC encourages visitors to stay a night or two, explore the hill and go walking or trekking. Some old bungalows belonging to state agencies are still open for rental, as are private units that have been beautifully renovated.

Education and conservation are in the corporation’s plans, thus its restoration of Edgecliff Bungalow, that now serves as the Penang Hill Gallery@Edgecliff with exhibits on funicular engineering, heritage and biodiversity, among other things.

In 2021, after the hill received its designation as a Unesco Biosphere Reserve, scientists were enlisted to spearhead projects promoting sustainable development and agricultural activities, particularly due to the prevalence of slope farming in the area. Their mission was to discover solutions that foster harmony between economic activities and environmental concerns.

unveiling_of_the_hills_second-generation_iconic_coaches.jpg

Looking at the growing visitor numbers, PHC is strengthening infrastructure and basic amenities to meet their needs for the next 20 to 30 years. “But we’re not going to alter the face of Penang Hill” because its unique appeal lies in its natural features.

“Every country I visit, I find a way to go up the hills. Twenty years later, you go again, it’s still the same. But people will return because they like the environment. They want to walk around and feel healthier when they do.”

People flock to the famous hills around the world again and again for their natural setting. Cheok cites, as examples, China’s Huangshan, Nikko National Park in Honshu, Japan, Yosemite National Park and the Rocky Mountains in the US, which his favourite places.

“We don’t want to overdevelop but have to be prepared for the influx of tourists so that when they come, they are able to enjoy the place and return safely.”

Safety is the No 1 priority at PHC and “it has become part of our culture”, he emphasises. Briefings for contractors are de rigueur and Cheok, who brings consultants in for inspections, personally goes out to do surprise checks. Are people working with slippers, barefooted, or with safety shoes?

“Because we are a government agency, we have also implemented an anti-bribery management system, which is important. Our procedures are strict and we practise open tender systems. That way, people feel safe working in this environment.”

the_third-generation_modish_blue_coach.jpg

PHC was incorporated in 2009 and started operations a couple of years later. Cheok was asked by then-chief minister Lim Guan Eng to help develop Penang’s iconic tourist attraction, “the most popular tourism asset under the state government”. He agreed in 2017, after a short-lived retirement from the technology industry where he spent 30 years as an engineer and later, a corporate executive overseas.

“This is the first time I’m running something to do with hills, but I’ve always been interested in nature. As a Boy Scout, I looked forward to camping and have done hiking all over the world,” he says.

Cheok had left his hometown of Port Dickson in Negeri Sembilan to further his studiees at Universiti Sains Malaysia after deciding Penang was “a better place” than Kuala Lumpur. Well, his son and two daughters were born on the island and his initial intention of staying one year at PHC has stretched to seven.

What he is doing now is creating SOPs so people will know there are methodologies in place and that these can be followed easily when implementing projects. “Decision-making has to be data-driven, not driven by emotion or hearsay. There should be proper processes and documentation.

an_aerial_view_of_air_itam_and_the_connecting_hilly_area_of_paya_terubong_they_form_the_main_areas_surrounding_penang_hill.jpg

“I personally believe in ISOs, so we continue to explore other quality standards to improve the way we operate. We’re doing this so we can uplift the organisation and hopefully, one day, become world-class. If not [that], at least near it, with the right people and strong determination.”

Looking beyond the 100th anniversary celebrations, Penang Hill Railway is encouraging people to share photos they may have of the hills, whether of their family or the railway while it was under construction. “We’re starting the collection because PHC is new and there are not a lot of records in one place,” Cheok says. The hope is for people to appreciate Penang Hill more, to cultivate and nurture interest in its rich history and, from an engineering perspective, the railway itself.

the_governors_official_hill_residence_in_bel_retiro.jpg

There are also the heritage bungalows, each unique in design, with its own name and history, the transfer of ownership and how many of them belong to the who’s who in Penang now. “Every bungalow has its stories, mysteries and romance, so it’s worthwhile to start recording them.”

Hills enfolded in green with clouds scattered above and changing shades of blue along stretches of coast in the distance have long inspired poets, artists, historians and photographers to come with books and art that express what captures their eyes and hearts. “It is a great legacy and Penang Hill hopes to see that,” he adds.

This article first appeared on Oct 16, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.