Taking the train to Bhubaneshwar was like entering another India. This was the timeless India rushing by outside the windows — of brown rivers, green fields, vignettes of villages on dusty roads, farmers toiling in the fields. The train journey itself was a reminder of a venerable institution beloved of, reviled by and quintessentially, India.

Tiffin was served in aluminium-foil covered trays — a creamy orange-coloured tomato soup in a cup, a “Soup Stick & Butter Chiplet” (bread finger with a knob of butter), white rice, a weak aloo curry, watery dhal, the choice of chicken or a paneer (cheese) dish, a tub of yoghurt and a sickly sweet gulab jamun dessert. The placemat, a single sheet of thin paper, advertised meals available on board, and Holiday Packages by the IRCTC (Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corp Ltd). It carried the stern admonition “Please do not pay tips”. Not unexpectedly, towards the end of the journey, the carriage attendant came around with open palm, followed minutes later by the cleaners who swept the carriage, soliciting tips.

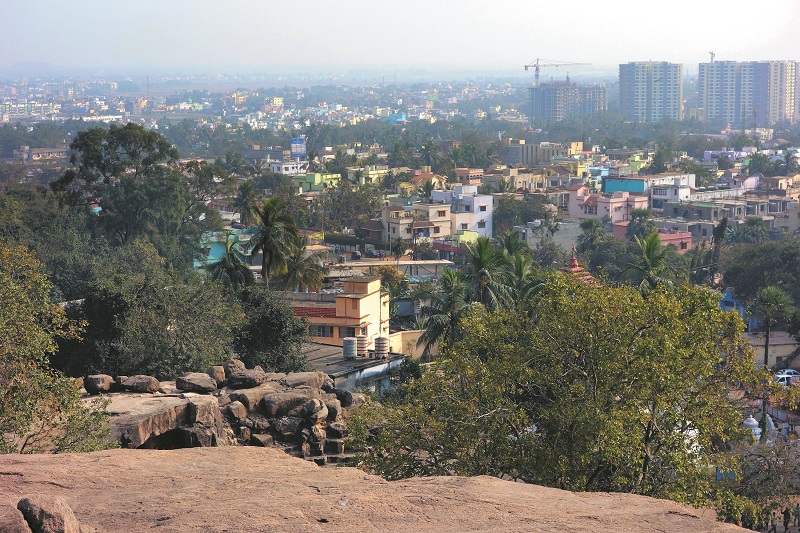

Bhubaneshwar is the capital of Odisha, an eastern state that suffers from a disproportionate development when its cultural heritage is compared to its economy. Not only is it the guardian of the hauntingly beautiful Odissi temple dance discipline, it also inherits a rich, distinctive cuisine and a striking architectural heritage in its temples, which was what drew me to the state.

In a country with hundreds of thousands of temples flung across the landscape, Bhubaneshwar is the temple capital of India. The temples conform to an architectural style called Kalinga, after a vanished kingdom. My guide to this faded glory was Pravat, an enthusiastic and sincere fellow who informed me, in all seriousness, that there are so many temples in the area because lingams grow naturally there, from the ground.

A lingam is a representation of the Hindu deity Shiva, a conical object associated with the male deity. An object of veneration, it is sometimes embedded within the yoni, associated with the female deity, with the unmistakable symbolism of fertility when taken together.

The morning after our arrival, we travelled back in time to one of the oldest temples in the city, the Parasurameswara Temple, dating to the 7th century CE, an astonishing 1,300 years ago. What staggered me was how advanced the architecture was, considering its antiquity, for it was magnificent.

A well-defined architecture was evident, with a towering Vimana and a porch called a Jagamohana in front of it. The arrangement was simple, with devotees in the front, lower porch, while the tower was the inner sanctum, the temple proper. Symbolically, the Kalinga style took its cue from the human figure, with a head, an upper and lower body, stylised into the architecture.

The entire building was encrusted with carvings in stone of stupendous intricacy and beauty, down to the details of curled toes and bent fingers of individual figures — unlike the stiff, two-dimensional representation of humans prevalent in church paintings in distant Europe at the time. Figures were fluid of movement and graceful of feature, naturalistic, three dimensional and sensuously full-bodied.

But there was even greater magnificence nearby, what is considered the gem of Odishan temple architecture, and one of the finest temples in India. It was small and exquisite, with divine proportions and distinguished by a graceful, curved stone gateway called a Torana. Bedazzled, I stepped into the cool darkness of the 10th century Muktesvara temple. It was empty of devotees, but there was a priest in the inner sanctum, placing flowers around the sacred lingam-yoni.

In later centuries, temple architecture evolved, with additional appendages such as religious dance halls and offering halls. These developments were evident in some of the larger temples, but I could only see from a distance the Lingaraj temple, considered to be one of the best developed Kalinga-style temples. As admission was was only to Hindus, I stood on a viewing pedestal outside the grounds to take in the details the temple with its adjoining and adjacent buildings.

The Odishan countryside was as poor and backward as its religious buildings were luminous and magnificent. Dusty village roads, brown fields, droopy figures in sun-baked villages formed the backdrop from which towering temples arose, like transplants from a distant, more advanced planet. Yet it was the forefathers of these people who built the temples, which were signposts to a glorious past.

One day, driving in the city, we chanced upon a troupe of dancers in front of a deserted temple. They were children, dressed in the jewelled finery of temple dancers, performing Odissi, the ancient temple dance of Odisha. The dance conforms to a discipline, expressed in mudras or hand gestures, foot and body movements and facial expressions. To the initiated, the dance is a retelling of a story.

Something clicked. Here, in the flesh, was the sinuous and stylised movement of the temple sculptures, a living link with the ancient past with dance and dancers immortalised in stone on temple walls and niches. I imagined a past when the countryside was in darkness and temples, the core of society, lit by flickering oil lamps. Villagers from near and far gathered at temples with devotional offerings. There was sound and hypnotic music. Dancers, dressed in robes that sparkled and glittered in the shadowy light, enraptured the audience with their rhythmic movement and expressions.

Religion guided peoples’ lives in spiritual and daily matters — the planting and harvesting of grain, community practice, education, family life, medicine and every other detail, with no separation between what we think of as secularism and religion.

One day, we drove out of the city onto an unpaved road, with empty fields around us. We crossed over a dry riverbed. The driver parked the car under a tree and we walked along a narrow footpath which led, eventually, to an isolated temple that was different from anything I had come across.

This was a temple form totally unrelated to other traditional temple architecture. It was circular, and roofless, or hypethral, dedicated to the 64 yoginis of the Tantric order. There are only five such temples in all of India, and this, the Chausathi Yogini temple, was one of them.

Statues of the yoginis, in black stone, were set into recesses in the low walls of the temple in a circular pattern around a central plinth mounted with figurines. The statues were delicately rendered, exquisite in proportion, detailing and posture. Many had been disfigured or damaged by vandalism, or in the course of war and battle, for the temple dated from the 9th century CE, but considering its exposure to the elements over the centuries, it was remarkable.

It was relatively distant from the city, yet it was not forsaken. Devotional offerings had been set up in a corner, with a couple of devotees in the middle of a ceremony. The temple exerted a primal, powerful draw, with the faces of the statues smiling at me from sightless eyes under the open sky, as if I had accidentally intruded into a private, sacred space.

As we left, we saw a yogi approaching us along the footpath with his assistant. The yogi wore only a covering made of tree bark around his lower torso. His grey hair and beard, streaked with white, were long and fell like a mane around his head. He was barefoot, but wore a necklace. His assistant, younger but similarly attired, carried a staff.

Pravat became wide-eyed and trembly, and told me, in a tremulous whisper, that we were in the presence of a very wise and powerful man. He fell to his knees and prostrated himself at the yogi’s feet. The yogi paused, and it came to me — the depth of devotion that moved a simple, rural people to construct the great temples, the expressions of their faith, all those centuries ago.