Two climbers rest during the descent towards the treeline (All photos: Lee Yu Kit)

A few days before our departure, our guide in Indonesia messaged me, warning of forest fires on the volcano we had been planning to climb and that the hiking trails were closed. The day before our departure, he confirmed that the trails were still off-limits and suggested an alternative venue. That is how we came to climb Mount Raung in East Java.

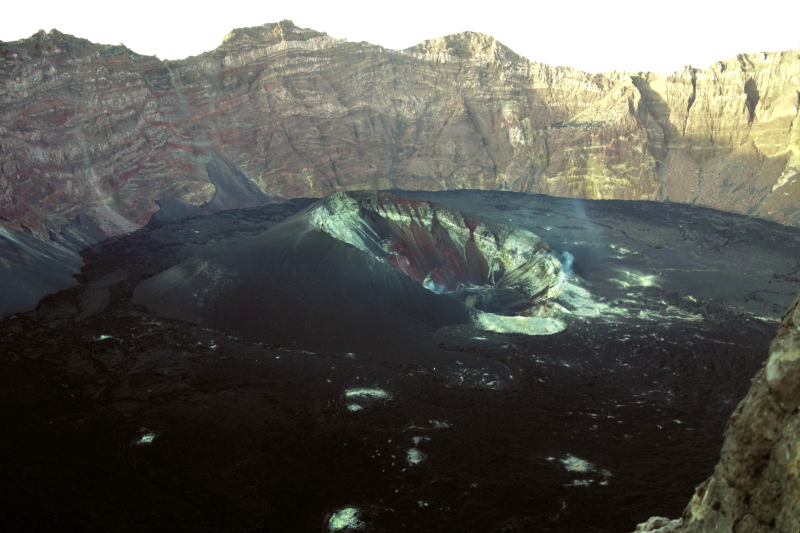

I had seen Mount Raung from the westernmost part of Bali, across a narrow section of sea. The volcano was massive, a perfect cone truncated at the top, its sides creased with gullies, its caldera ringed with barren rock. It is one of the least-climbed volcanos in Java, sitting at the remote, easternmost part of the island. At 3,332 metres above sea level (MASL), it is the seventh-tallest volcano in Indonesia and one of the most active. Satellite maps reveal a black lava lake in the fearsome-looking caldera, with a smouldering lava cone within.

There are two routes up Mount Raung, a southern, more technical one requiring ropes and helmets, and the gentler northerly route, which we were to take.

caldera.jpg

The seven of us met at Surabaya Airport and our minivan took us on a toll highway to Probolinggo, where we met up with our guide, Agus. I had climbed Mount Semeru with him several years ago, and recall how he had paused midway to perform his morning prayers as the light from the eastern sky breathed life into the day.

It was almost midnight when we reached Sumberwringin and pulled up at our homestay, a low Dutch-era building with large gloomy rooms. I collapsed onto the bed, awakened only by the call to prayer from the nearby mosque to a bright, cool morning. We piled into the back of a flatbed truck with no suspension to speak of for a 40-minute ride on a rutted track through pine and coffee plantations, to be deposited at the trail head.

It was the dry season — the sky was a cloudless blue and the vegetation browning. It was dusty underfoot as we and our porters, who carried tents and food, trudged up the narrow footpath, past newly-planted Robusta coffee saplings and later, scrubby forest. None of the campsites were near sources of running water, which meant the porters had to carry our water supply.

Because the mountain is infrequently climbed, the track was litter-free, a welcome contrast to some of the more popular volcanos. The only other people we met during our trip was a small party of hikers on their way down.

After partaking of a packed lunch at an open campsite, we continued the trek. The slope was perceptibly steeper and it became cooler and drier. The lush and dense lowland forest gave way to more open forest, with pine trees and carpets of flowering shrubs.

camp.jpg

In the late afternoon, we reached a lovely campsite perched on a ridge. Low shrubs with white and purple wildflowers carpeted the terrain, interspersed with tall pine trees. It was a wide, open space, a gentle slope into which flat platforms had been cut for pitching tents. This was Pondok Angin or Camp 5, where we were to spend the night. The porters set up tents under the trees and collected dead branches for a fire to ward off the gathering chill. We were at 2,500 MASL.

As the evening deepened, Agus cooked us a hot dinner, with watermelon for dessert. Clad in sweaters and jackets, we gathered around the roaring fire as the setting sun brushed the sky with pale hues of pink and orange. Occasional breaks in the cloud cover around us revealed a rugged, forested ridge opposite the steep ravine next to our campsite, while further up, we caught glimpses of the barren rock leading to the caldera.

The wind whooshed and whistled outside my tent, occasionally rattling it, and the temperature dropped further. I spent a restless night, tossing and turning. At about 3am, I stepped out of the tent. The wind had stopped and the cloud cover had lifted, and my breath caught in my throat at the view of the country far below. Peaceful and quiet, ablaze with the lights from distant towns and cities. The velvety dark sky dotted with the cold glitter of stars.

Agus and the porters had slept beside the fire. The cold and silence was like a blanket thrown around us. We had a snack of toast and hot drinks, clad in sweaters, gloves and beanies. Headlamps left our hands free.

We began our ascent, brushing against the undergrowth, our headlamps throwing pale pools of light ahead of us. After an hour, we paused at a campsite on a narrow, flat piece of cleared land.

There was a marker at the treeline in memory of a hiker reported missing decades ago. The solidified lava beneath our feet was soft.

Shortly afterwards, we were above the treeline and onto the barren rock that sloped upwards to the caldera.

climbing.jpg

A horizontal slit of crimson appeared in the eastern sky and the rocky terrain around us emerged in the faint glow of the sun suffusing the dawning day. Turning around, I beheld the dense vegetation from which we had emerged, cloaking the flanks of the great volcano, and beyond that, the spread of eastern Java, partially obscured by cloud cover. To our right was the massive forested range of Mount Argopuro, which is home to the longest mountain trail in Java.

The sky was clear and the slope angled sharply upwards, with little of the loose scree that impedes progress on many volcanos. Far above, a small Indonesian flag fluttered and snapped in the wind, marking the rim of the caldera.

After a short scramble over rocky terrain, I stood at the flagpost. The caldera was awe-inspiring, a rare glimpse into the raw power that lay beneath our feet. The void stretched out before me, a yawning 2km across in a ring of craggy rock with vertical walls falling into the solidified black lava lake in which nestled a black ash cone that emitted a wisp of smoke.

It was like looking into an alien landscape, hidden by the rim of rock. Agus recalled how, in 2017, the volcanic cone spewed hot lava and ash, resulting in the lava lake. Mount Raung is still very much active, a cauldron fuelled by the hellish temperatures beyond the mantle of the Earth.

On the descent, near the treeline, Agus pointed out shrubs of wild petai plants, shrunken from the poor soil conditions. White edelweiss flowers provided a soft touch against the stark beauty of the volcano. Dreamy and alien in the dawn, the emerging light of day threw the landscape into harsh relief, with deep shadows, sharp-edged rocks, dusty gullies and dangerous ridges.

trail.jpg

We descended quickly, pausing at our camp for a full breakfast. Further down the mountain, Crystal emitted a shriek before tumbling down the side of the path into a ravine while SB became temporarily airborne after tripping on a tree root. However, both emerged unscathed, if a little shaken. In the afternoon, we reached the coffee plantations, where our suspension-less flatbed truck was waiting to transport us back to our homestay.

Over dinner that evening, I reminded Agus that he had promised to tell us more about the volcano.

“Ah, yes,” he said with a smile. After a pause, “Did you hear anything unusual last night?” he asked. None of us had.

“Raung is the most haunted volcano in East Java,” he said. In the silence that followed, he elaborated. “After independence, the people here were no longer afraid of the Dutch. They rose up against them and took three Dutch people from this building.” We knew that our homestay had once been a Dutch administrative centre.

“They marched the prisoners up the volcano, where they hung them from a tree. The place where they hung them is called Pondok Mayat, and the camp just before that is called Pondok Demit (evil). The camp after that is called Pondok Pocong (In Indonesian and Malay folklore, pocong is a ghost wrapped in a burial shroud that hops around because its ankles are tied).

“And where are these camps?” I asked.

Agus smiled. “I didn’t want to tell you this when we were on the volcano. Pondok Mayat is Camp 5, where we camped last night, and Pondok Demit is Camp 4. The camp above Camp 5, near the treeline, is Pondok Pocong, and the tree that was used for the hanging is the one behind one of your tents.”

We had come to Java to climb one volcano, and because of unexpected circumstances, had climbed a different one. In spite of the grisly story of the haunted volcano, it had been a lovely climb and discovery that there are still wild places nearby, where nature reigns untrammelled in all of its glorious majesty and beauty.

This article first appeared on Jan 27, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.