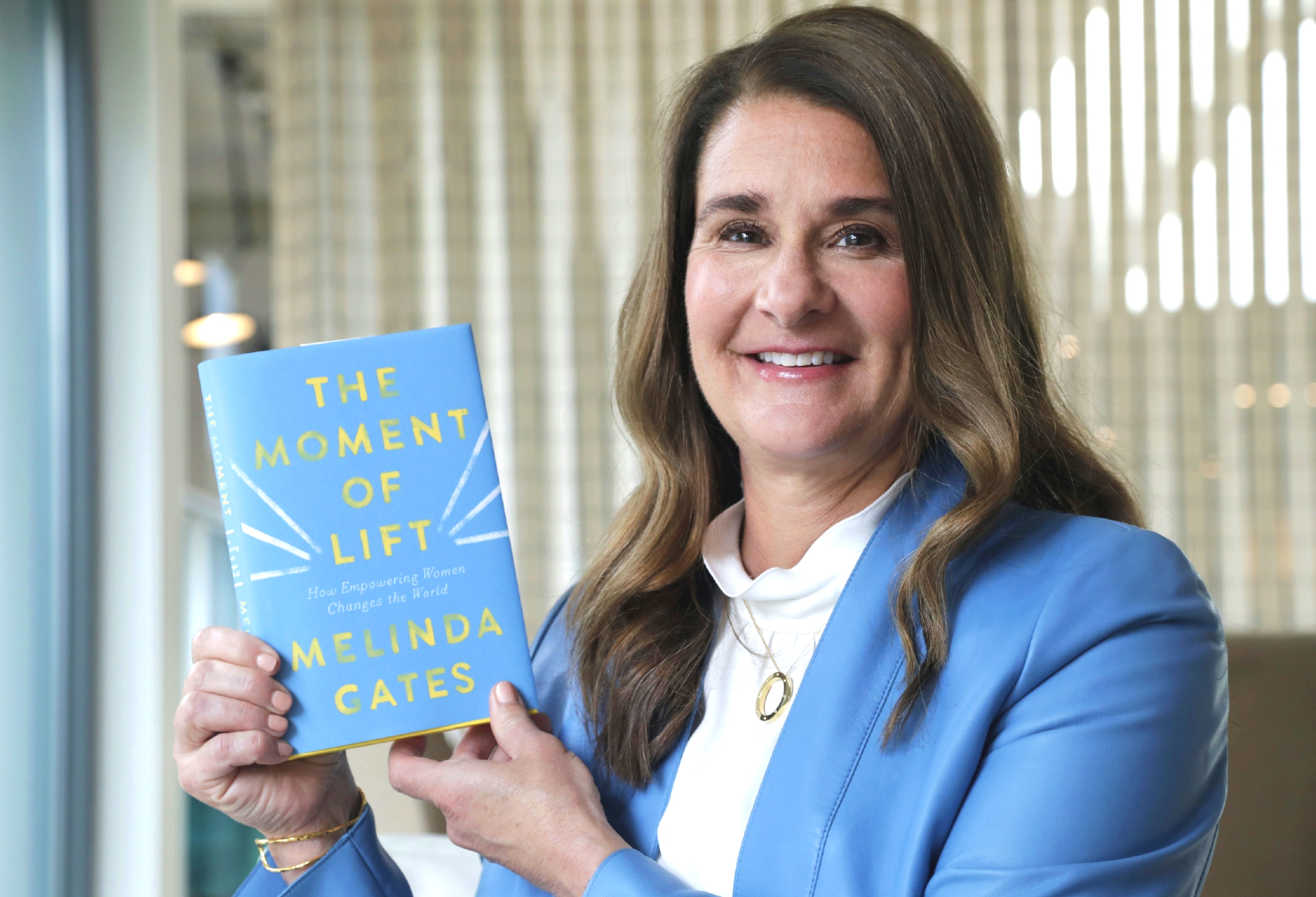

Melinda shares the stories that have captured her heart while travelling around the world to see for herself what the sick and poor needed to propel their lives forward (Photo: Evoke)

“If you want to lift up humanity, empower women,” says Melinda Gates, co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The realisation of this big truth came to her several years into the formation of her and her husband’s philanthropic organisation, which goes out of its way to solve challenging world health problems. Making life better for the poor and disadvantaged is at the forefront of its mission.

A computer scientist and former senior manager at Microsoft (where she met Bill), she became the co-founder of one of the world’s largest private charitable organisations when she decided not to go back to work after having her children. It was formally set up in 2000 with an initial mission to save children’s lives by improving their living conditions through vaccinations. To date, the foundation has dedicated over US$45 billion to help solve what seems to be difficult issues in global health and poverty.

From deadly diseases such as HIV, malaria, tuberculosis and even clean sanitation, to family planning, access to education and improved farming techniques, it searches for interventions and innovations that will create a positive change for mankind. Its humanitarian efforts cover the US, Africa, Asia and Southeast Asia, reaching out to the needy who are left on the sidelines.

fc235501_800_v01.jpg

In her first book, The Moment of Lift: How Empowering Women Changes the World, released in April, she shares the stories that have captured her heart while travelling around the world to see for herself what the sick and poor needed to propel their lives forward — solutions that would have a positive impact on their families, community and the future generation.

The lift-off analogy that Melinda uses to define the moment of change and elevation was a result of her growing-up years as the daughter of an aeronautical engineer who worked on the Apollo programme. Together with her mother and siblings, she spent many years watching with excitement the spaceship’s lift-off. “The moment of lift is when the forces pushing us up overpowers the forces pulling us down” she explains.

On many of the trips she made to observe the foundation’s vaccination programmes, Melinda would sit on the ground talking to the women who had walked miles to obtain the vaccine for their children. During these “on-the-ground connections”, she discovered how desperate the women were for contraceptives to ease their life. Many could hardly afford to feed their children, some had become very ill after multiple births and there were many stories about women and their babies dying at childbirth.

billandmelinda_gates.jpg

It was through these direct sessions that she recognised that there was an intricate relationship between gender and global welfare problems. The advancement of women would directly impact the welfare of their family and, eventually, society at large. This was her “huge missed idea”.

Family planning was the first step towards their emancipation and she began to champion the availability of contraceptives, despite cultural and religious sensitivities, for women were getting pregnant too young, too late or too often for their bodies to endure. Most did not have the ability to feed their children adequately or educate them.

Melinda, a devout Catholic, felt she could not look the other way, especially since these women had opened their hearts to her. So, she began to speak publicly about the importance of providing women with the choice to plan the progression of their family. This awakening led to her confronting other issues faced by women and children who were exposed to prejudicial conditions.

She realised she needed to support the empowerment of women as a whole by helping them break down the cultural and religious barriers that held them back. Additionally, she needed to make their life more equitable by increasing educational opportunities as well as providing economic breaks to help upkeep their family.

The book covers a wide range of issues, including maternal and newborn healthcare, the socioeconomic benefits of family planning and women empowerment, the importance of education for girls to improve their status and prevent abuse, child marriage, young sex workers and even the brutality of female genital mutilation. Towards the end, she writes on the importance of equality at home and work and in religion.

She delivers both sides of the story — the cultural and political background to the issues and how the foundation actively addresses sensitive agenda through collaboration with activists, governments, village communities and religious elders. Melinda also uses this occasion to highlight the successful work done by other humanitarian groups and courageous individuals in the field.

Some of the more heartbreaking stories include efforts to reduce newborn mortality in impoverished parts of rural India through the provision of maternal and neonatal care. She tells of how a health worker had to hold a cold baby closely against her own skin to ensure it would not die from hypothermia because the family had rejected the infant, believing that evil spirits had caused the mother to faint during childbirth.

063_850095002.jpg

Another story involved a woman named Meena, who begged Melinda to take her child because she was too poor to give it a good life. There were also stories about children from lower classes begging for the opportunity to receive an education. In Africa, she tells about 13-year-old Kakenya from Kenya’s Masai community, who was confronted with female genital cutting and forced marriage. But not all of the stories have sad endings. Melinda shares positive outcomes that have transformed girls and had a multiplier effect on their community.

Fortuitously, when Warren Buffet pledged the bulk of his fortune to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, it was able to expand to new frontiers. From its initial goal of solving global health issues, it moved on to improving gender equity and reducing extreme poverty. The foundation focused on farming as 70% of the world’s poorest get their income from cultivating small plots of land and most of the workers were women.

Through its “Giving Pledge” programme team, the foundation has managed to attract other billionaire families to give half or more of their money to support its activities. Today, there is much interest in the development of family philanthropy and how to run an exemplary result-oriented aid organisation professionally.

The book is a big read — long in some sections and sometimes crammed with statistics and excellent case studies. An evidence-based writer, Melinda supports her findings with data and moving accounts of the people she has met. But as you push through, the flow gets better. The narrative becomes more powerful and the overall theme on the importance of supporting gender equality to improve the welfare of the poor is embedded in our moral consciousness.

It is also partly a memoir — the discreet, empathetic and cerebral Melinda, who has always shunned the limelight, weaves into the book her own story of a happy childhood, outstanding educational and career achievements, and how she evolved from career woman to mother and finally co-chair of the foundation, sensitively revealing the quiet yet egalitarian relationship she has with Bill.

By the end of the book, one understands the overall vision behind the team that has been leading one of the most equitable and benevolent foundations in the world. To empower the women in poor and disadvantaged conditions is probably the most important reason Melinda wrote this bestselling book — she amplifies their once-unheard voices. It is no wonder that Fortune magazine paid homage to this couple by voting them among the top leaders of the world in the 21st century.

This article first appeared on June 10, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.