I certainly did not expect to walk into a state of enlightenment, but that was the philosophical experience that is Tan Zi Hao’s first solo exhibition titled M. At the risk of jumping the gun, I walked out wishing his works were the kind we could have more of in our museums.

This was not the first time I had come across the young artist’s work. Last year, during the Singapore Biennale, a weird-looking skeleton caught my eye. The name of the work was The Skeleton of Makara (2016), one of Tan’s imagined creations that reference Southeast Asia’s penchant for mythology.

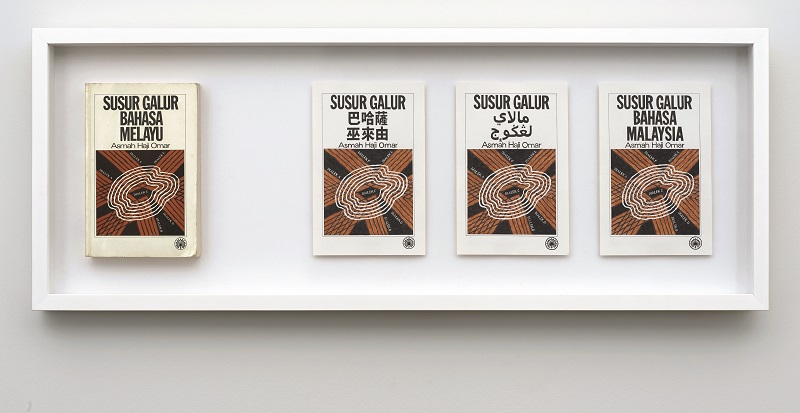

That work questioned the truthfulness of the representation and politicising of history. In many ways, M is an extension of that and a fuller presentation of the artist’s questioning mind. The multidisciplinary exhibition’s anchoring theme is language, its delicate relationship with the nation and, in a broader sense, the relationship between mother tongue and mother nation.

And while the works resonate with today’s sociopolitical state on a global scale, they are firmly rooted in the Malaysian context. At the entrance, we find a reproduced sign of a Kedai Pajak Gadai (pawnshop) deliberately placed to be seen by passing traffic as it originally would have been.

One of a few signs recreated for this exhibition, it brings renewed attention to the hierarchy of languages, which is inadvertently politically and ideologically influenced.

“Many of these shops were operated by minorities but it’s interesting that even so, the minority’s language always came after that of the majority,” says Tan, a trained graphic designer. “Also, there is a tendency to not include the languages of the other minority groups. So, there is a certain kind of exploitation to this visual form.”

In Addressing Home (2017) and Unaddressing Home (2017), he explores the ties between language and one’s geographical identity. The text-based artworks play on the etymology of words using a home address. In the former, Tan simply translates the meaning of what seems to be his Malaysian home address to his first language of Mandarin, and from that to English, before translating it back to Bahasa Malaysia. The result is entirely different from the original address. Similarly, in the latter, he renders the address unrecognisable by looking for the etymology of each word.

An accompanying essay on this work sees Tan philosophising on how language puts us in our place, often without a choice. Indirectly, he also questions his identity as a minority with a mother tongue that is different from the national language.

At this point, you would be forgiven for reeling from the sum of what Tan is trying to convey. But while M is in essence a to-date visual homework for the PhD student — he is pursuing Southeast Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore, focusing on discourses of power in a post-colonial setting, no less — it is refreshingly stimulating even on the surface level, especially for Malaysians.

Take The Danger of Translation Lies in That Which is Left Untranslated (2017) — the series of 18 signs rendered in the form of the familiar red-and-white “Bahaya” signage sees English, BM, Mandarin and Tamil translations of one word painted on each. Some refer to national and political incidents, such as May 13, Ubah (Change) and Bersih (Clean), while others are generic words, yet the connotations are telling: Anjing (Dog), Yahudi (Jew), Kaum (Race), Tanah (Land), Bumi (Soil) and so on.

“What I’m looking at here is the untranslated because every translation is incomplete. And it’s the [residue] that is dangerous. In different languages, some of these words carry different connotations and weight. Some are based on incidents I resonated with, such as Aku and Idiot in English, which is a reaction to Anurendra Jegadeva’s artwork, I Is For Idiot,” explains Tan.

He clarifies that he is not attacking any particular language or culture but is critically questioning the effects of the nationalisation of languages and the role this plays in sociopolitical superiority. “I don’t have all the answers but I feel a lot of our problems come from an assumption that language is tied to a place, a nation. Without this relationship — this bondage — I don’t think people will feel so offended about a lot of things when they comment on language,” he says.

Acknowledging that a lingua franca is important and necessary, Tan adds that the problem is when it gives one a sense of legitimacy over another, be it in language or identity. “It enables offence. We do not think how language is used as an important criterion that constitutes what is a human being. That’s why foreigners or migrants are always called ‘undocumented’ or ‘aliens’… as if their physical existence as humans itself is not enough to prove that they belong.”

Bringing home this point is perhaps the anchoring installation piece, a/āgama (2017). Drawing from the etymology of the word “agama” in Sanskrit, which is separated from the BM version only by the macron diacritical mark (emphasised by the shape of the installation box), Tan uses provocative imagery to comment on the lack of peaceful coexistence and true multiculturalism despite the sharing of a same word. Within the box, he creates an imaginary world where the divided are finally united.

'M' is on view until Nov 25 at A+ Works Of Art, G8, d6 Trade Centre, Jalan Sentul, KL. Tues-Sat, 7pm. For more information, call (019) 915 3399.