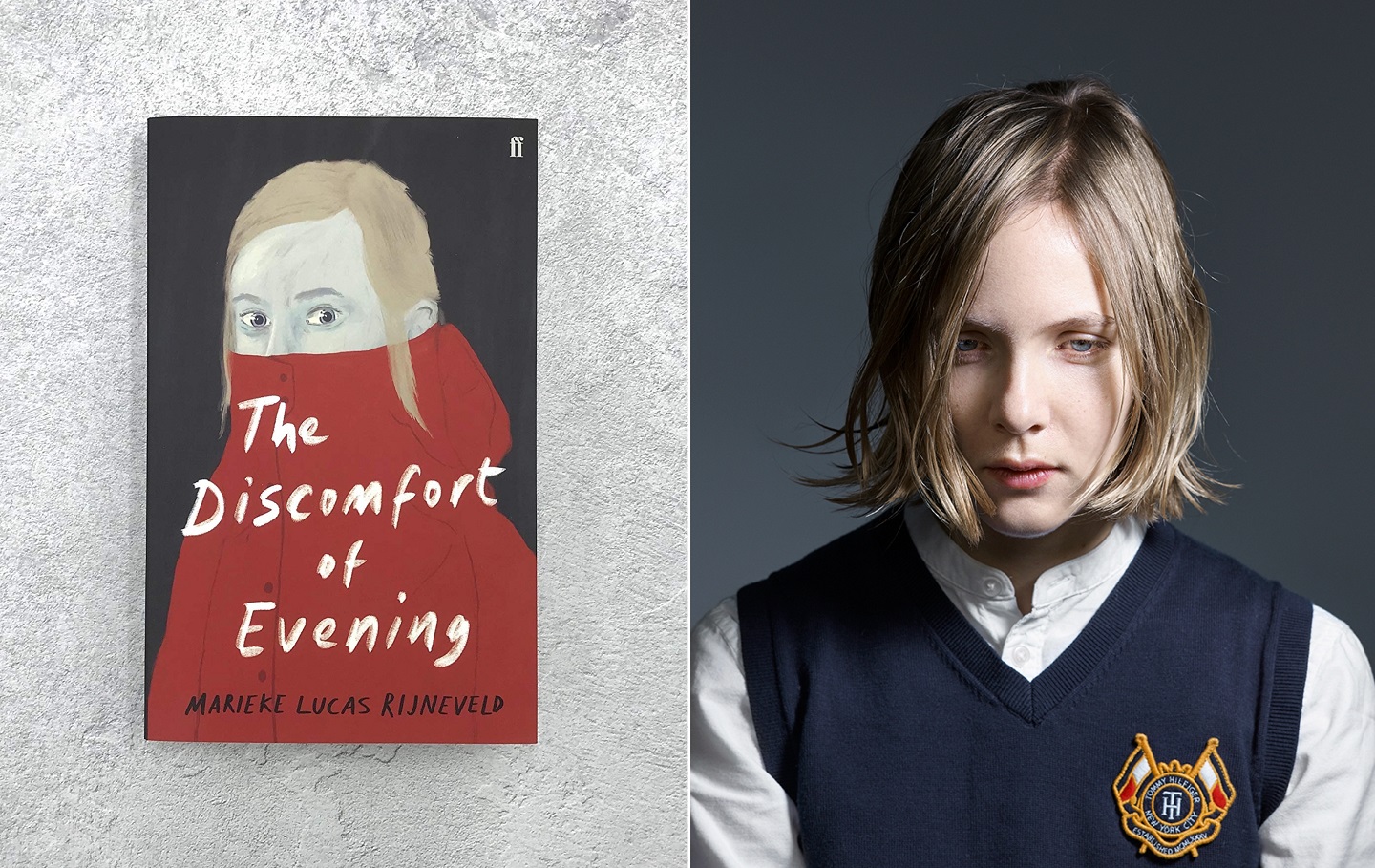

The Discomfort of Evening is a moving, if harsh, signal of the powerful, impressive writing of a young author on the interior (Photo: Marieke Lucas Rijneveld)

Few subjects could converge to create the perfect cauldron for a literary prize — women, red dogs, a 14th century German jester making an entrance in a new incarnation, the Argentinian Pampas, wild horses, an unintended trade of lives where a young brother is sacrificed for a rabbit, the murder of the Witch of La Matosa in rural Mexico, Persian folktales confabulating within the oppressive fortunes of a revolution struggling to survive — all in a climate of urgency in a world gripped by the uncertainties of a pandemic.

Since being cited by several literary journalists as “fast becoming the more significant award, appearing an ever more competent alternative to the Nobel” upon the announcement of its first recipient, the powerful Albanian novelist Ismail Kadare, the International Booker Prize continues to gain an ascendency that rivals (and perhaps even outrivals) its antecedent, the exclusively English language writing, Commonwealth-centric Man Booker Prize. The increasing anticipation that greets the annual announcement is best measured where it matters most, at that great “index of worth” — the bookies.

Few literary prizes worth a name would fail in delivering a suitable controversy. Unable to rise up to the occasion surrounding the joint award of the Nobel Prize for Literature to the brilliant if politically eccentric Austrian novelist Peter Handke in 2019, the announcement of the International Booker Prize longlist for 2020 appeared suitably subdued but for the charges of plagiarism directed at one of its finer selections, the South African novelist William Anker’s brooding, sinewy novel of early colonial Africa, Red Dog. Accused of heavy lifting from one of the finer creations in American fiction of recent decades, Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, Red Dog induced a quite forceful and far reaching debate about the art of “literary borrowing” and the nature of plagiarism. Snared in the middle of this tug of war between theft and being able to see the proverbial woods from the trees, Anker’s fine novel was nevertheless left hanging at the levels of the longlist.

the_discomfort_of_evening.jpg

The shortlist boasted an increasingly impressive array of literary imaginations, arced principally by the representation of women — four of the five shortlisted were women — and the increasing predilection in contemporary literature for the art of literary retelling.

Taken together, the quintet of novels seem to seize our zeitgeist — that struggle to make sense in an age of populist politics, environmental calamity and a present that appears to exist adrift from a complex and capacious past — in a world existential crisis that appears to play in loop. Daniel Kehlmann’s Tyll, a reimagining of a 16th century practical joker from the Germanic trove of fables, perhaps grasped this attitude best, “When God wants to make a person, why does he do it in another person?”

From this literary state of mind, the other novels in the quintet, significantly all by women, and in contrast to the hapless, despairing though brilliant Tyll of Kehlmann, begin the act of literary digging, literary shattering and literary recasting that is increasingly becoming the domain of women in contemporary writing (not that any of these literary regions have been remote to the woman writer’s imagination. There is no more enduring work of the destructive nature of unbridled reason, after all, an even greater curse of our times perhaps, than Mary Shelley’s instructive Frankenstein). But this art of claiming myths, entering realms of murder, magic and landscape, is fast emerging as the literary domain of the woman writer.

Of the quintet, a personal favourite remains the Mexican journalist and novelist Fernanda Melchor’s bewitching Hurricane Season — a narrative of murder in a fictional small town in Mexico digs deeply into the vestiges of misogyny, superstition, the enduring spectre of “the witch”, the timeless draw of the occult and the hovering weight of deep sexual complexities. Powerfully conveyed by the translator Sophie Hughes, the novel comprises narrative stutterings, rhythmic incongruities and brazen diction.

The contrasts between the quintet created a suitable tension of narrative form and originality of voice, inspiring a literary terrain that is at once diverse and quixotic as well as resonantly varied.

The eventual choice of Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s movingly laconic The Discomfort of Evening marked the return of the novel of the interior. Set amid a small farming community of conservative Calvinists in Holland, it commences with a young girl, angered for not being allowed to go ice skating with her brother, calling to the heavens that her brother die instead of her rabbit, only to discover later that her brother does die, drowning beneath broken ice.

The Discomfort of Evening is a moving, if harsh, signal of the powerful, impressive writing of a young author on the interior — a literary form made especially important by Dutch writers such as Louis Couperus, author of the novel The Hidden Force, who set their novels on the deep existential anxieties in the Dutch East Indies.

“We only knew about the harvest that came from the land, not about the things that grew inside ourselves” may well be the defining few lines that encapsulate their preoccupations of all the works in the shortlist, marking a return to all those fundamental features that have shaped and inspired the most lasting of literary imaginations — the existential, the elemental, the mythical — a good departure from the boredom of the identity novel soon to be revealed in the other Booker prize, the Man Booker Prize.

This article first appeared on Sept 7, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.