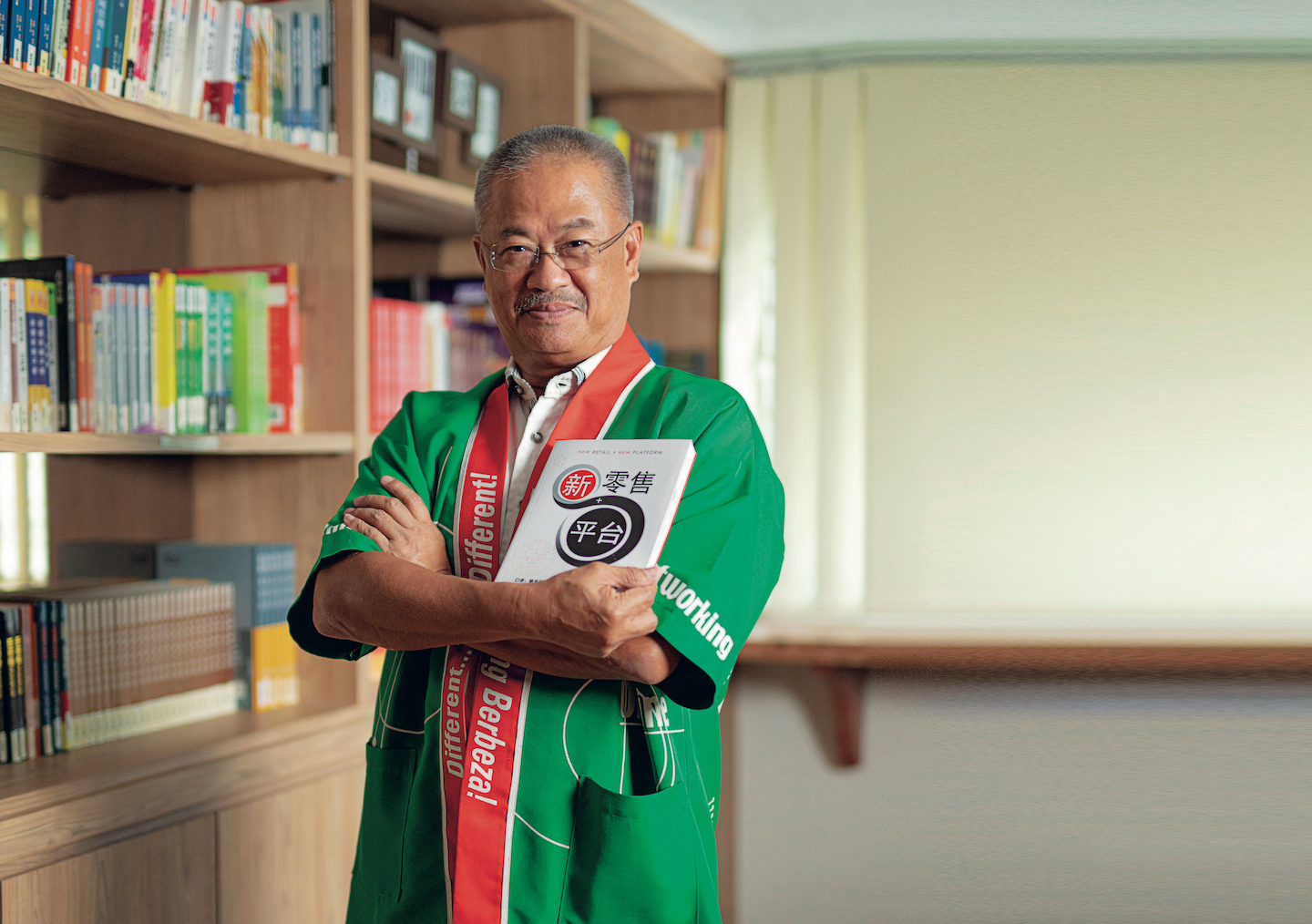

K H Lim has proven to be the exception rather than the norm (All photos: Senheng Electric)

It is not very difficult to understand why the team behind the EY Entrepreneur Of The Year Malaysia made K H Lim the winner of the master category in this year’s edition of the accounting giant’s annual initiative, which recognises the innovative and industrious nature of the nation’s entrepreneurs. Founder and group executive chairman of Senheng Electric, Lim displayed an impressive ability to adapt to the times and transform his business from what was once a mom-and-pop store into one of Malaysia’s largest consumer electronics retailers.

The man can also tell one hell of a story, and had that been an official category, he would have likely swept that up too. Remarkably open and displaying a beguiling honesty that traditional business owners of his generation generally are not known for, Lim is equally descriptive about his successes as well as his losses, detailing the mistakes he has made and how he learnt from them. A visionary leader who established a digital presence for the company long before many of his competitors, Lim continues to embark on boundary-pushing initiatives that utilise the power of data, the internet and even Jack Ma.

The challenges that face an entrepreneur are aplenty, yet his retelling of his journey, even the hard parts, is tinged with an infectious sense of joie de vivre. And yet, doing something on his own was never even on the cards for Lim, who started his career as a salesman in a family-run electronics store. Over a video interview from his office, Lim — sporting a Senheng branded yukata-style jacket and broad smile — is so eager to get started that I’m barely able to get a word in edgewise.

“With my first employer, I was very comfortable. I was good at my job and the boss treated me like family. Then, something happened! The second-generation owners of the store came back from the US after finishing their studies. This young man, who was almost my age, came back with many ideas, but no experience. He was based in the office, and I was handling customers and suppliers on the shop floor. He’d come to the shop and say ‘this is the wrong way’ and ‘this needs to change’ and I tell you, after a while, I was so fed up. Ok lah, in the US things are very advanced, and Malaysia is not so far ahead!”

senheng.jpeg

Although the family intervened and took Lim’s side, he knew his time was up. In a forward-thinking move that would define his future, the-then bachelor realised it was time to strike out on his own, and he had accumulated enough knowledge and resources to do so. Once he became a husband and a father, he knew that working for someone would not give him the independence he needed. “I can’t say he was wrong, but the entire situation wasn’t right for me,” Lim recalls diplomatically, referring to his former employer’s son.

Lim and his two brothers, K C and K Y ploughed in RM30,000 each — in the late 1980s, it was an inordinate amount of money — and started planning the new business, right from its name and logo to what it would sell as well as how the brothers would split the work. With his charismatic personality and charm, Lim was the ideal person to run the shop floor and deal with customers. Senheng was born on Sept 1, 1989, in a space that was under 1,000 sq ft in a half shoplot in Pandan Jaya, Kuala Lumpur.

The early days were difficult, Lim recalls. “Thirty-one years ago, when I wanted to talk to brands like Sony or Panasonic, no one wanted to support me or open an account with me. I had no brands, and no suppliers, no salespeople, no branding, and of course, no customers — I started from zero. But I worked very hard, and I am a skilful retail salesperson, so even with a small shop, my sales grew every month.”

He grins, and mischievously adds, “There used to be queues to come to the shop — I think, because back then, I was young and handsome, and easy to talk to. I could also read their minds and help them buy what they wanted. So, they would call their friends to shop from me.”

In just seven months, Lim made enough money to open a second branch, which his wife ran, and soon enough, a third. He was careful to keep bridges to the past intact, however, and benefited greatly from the good relationship he maintained with his previous employer as he became one of his most trusted suppliers.

Lim and his family worked very hard and were often in the shop from dawn until late at night every day except for the first day of Chinese New Year. The first six years of Senheng were extremely successful, and as the brothers basked in their success, they indulged as was appropriate — in particular, golf, which Lim would play four to five times a week.

But beneath the veneer of outward success, trouble was brewing. “When you are young, you think that it is best to get rich fast, and it is very easy to be distracted. I was hooked on golf and because I was paying less attention to the business, customer service also became very bad. We recruited sales people with poor attitudes.”

The Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s was around the corner, and while Lim was aware that there were some issues plaguing the company, its full scale was not yet apparent. He possesses an immaculate ability to recall details, and clearly remembers sitting down for his morning coffee at a kopitiam near the office when he read the damning news about the recession that would alter the course of many economies back then. Having lost his job during the recession of the 1980s and having to flip over his mattress to search for spare change to buy dinner, Lim refused to allow history to repeat itself.

“I was very worried I would lose my job again, or worse, lose the company,” he says. “So, I went back and looked at everything. I discovered we had over 100 problems in the company! I had too many shops, and that was itself a problem. We conducted an internal brainstorming session and solved the issues one by one. We took more than a year to sort it all out. We looked into business processes, customer service policies,and all the SOPs repeatedly. One-third of my suppliers were filtered out, because we carried too many unbranded products that didn’t even have spare parts. From that exercise, Senheng was reborn into a store that carried better-quality products.”

Lim swings around in his chair thoughtfully. “Till today, I thank George Soros for saving the company, because if not for him, Senheng would have closed down in three years from then.” The impact of the crisis even affected his personal life — a proud Chinese businessman who only spoke Mandarin to his staff and at major events, he started to learn English so he could better communicate with overseas suppliers. Lim enrolled his children in English-speaking kindergartens and learnt more of the language by speaking it with them.

According to him, there were only two points in Senheng’s 31-year history where sales dipped. The first time was in 2000, which led him and his team to transform the company’s many retail stores from its mom-and-pop set-up to something more professional. The second time called for more drastic measures, as the company recorded less-than-desirable results from 2014 to 2016. The rest of the industry was doing well, but even with their e-commerce platform up and running, Senheng was not keeping up.

“I happened to catch Jack Ma at a seminar and he said the race for online sales was over, it’s now the era of new retail and this would last another 30 years. What is new retail? I wanted to know what it was and I wanted Senheng to do it,” Lim says, and that is how 30 of his staff members found themselves at the Alibaba Business School in China to learn about it.

Blurring the boundaries between the physical bricks-and-mortar space and virtual e-commerce stores, Alibaba’s “New Retail” vision outlines omnichannel experiential retail as the future of the retail industry. In essence, Alibaba strives to disrupt various forms of retail by integrating online technology into traditional retail modus operandi to enhance the overall customer experience. Lim localised the model for Senheng into a multi-pronged strategy that standardised pricing, promotions, membership benefits, mode of payment, inventory, logistics and customer service for both online and offline touchpoints, creating a seamless buyer experience. The trip to China was in early 2017, and in a matter of months, his plan was implemented. The effects on sales and foot traffic were immediate.

By the time the pandemic hit the nation last year, which resulted in a soaring demand for home appliances such as breadmakers, home printers, PCs, tablets and televisions, Senheng had refined its proprietary app to engage better with its growing customer base. It went from merely pushing information to buyers to becoming a more engaging platform that Lim calls a telemarketing app.

shapp.jpg

“People know about telemarketing, people know about apps, but combined together? It was a new thing,” he explains. “With this, we can send videos, messages, pictures — send a lot of things! During lockdown, we applied more of a soft approach by telling customers that they could communicate with us through the app, and we could also see what their concerns were. Even though our shops were closed, we managed to do RM60 million in sales through the app. Even after our shops could open, we continued to use this tool.”

In January and February, sales increased by 20% and 40% year on year respectively. But Lim is not taking these wins for granted — he already has in place three initiatives that will continue to drive growth. The first is a customer data platform project that will drive conversion and grow its database. The second is a key opinion leader initiative which makes everyday customers active social media influencers and, finally, a rewards centre that acts as a virtual marketplace for customers to earn and spend Senheng tokens.

The Senheng app, launched in 2016 to be more utilitarian in function, will also undergo a massive overhaul to make it more lifestyle-driven. Outside of serving as a repository of customers’ receipts, warranties and reward points for their purchases, Lim hopes to provide access to games, interactive activities and even food delivery services. “We have a lot of ideas for this app, and we believe Senheng is no more just a retail company. It’s a tech company that serves retail needs.”

The expression “an old dog will learn no tricks” first appeared in the book Divers Proverbs, by Nathan Bailey, which dates back to 1721, making it approximately 300 years old. We know now that all dogs can be taught anything; it entirely depends on who is doing the teaching and what those lessons are. The saying is obsolete, and so is the notion that older people are not inclined to do anything new — we are happy to say Lim is proof, and I daresay the team at EY would have thought so too.

This article first appeared on May 10, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.