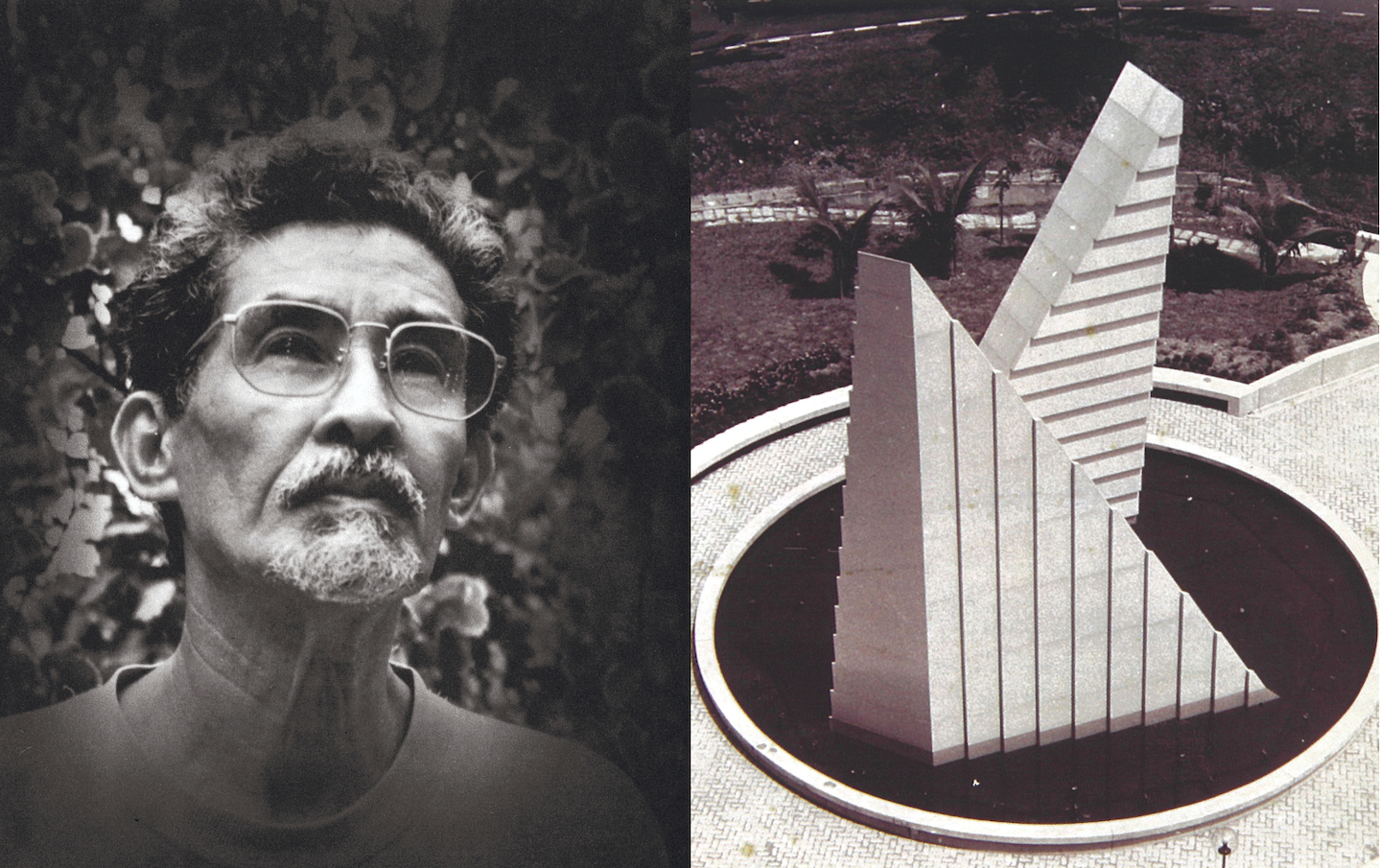

Datuk Syed Ahmad Jamal (left) constructed 'Puncak Purnama' in 1986, which was demolished by DBKL 30 years later (Photo: National Art Gallery)

July 1, 2021 marks five years since Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur brutally tore down Puncak Purnama, a public sculpture in central Kuala Lumpur created by National Art Laureate Datuk Syed Ahmad Jamal. DBKL said the sculpture had become dilapidated but the destruction triggered protests among the Malaysian art community.

Syed Ahmad was first commissioned in 1985 by the United Malayan Banking Corporation to create a suitable artistic landmark in a small park adjacent to the UMBC headquarters in Kampung Attap as a gift to the people of the city.

Puncak Purnama was unveiled in 1986. It comprised two triangular structures — 9.5m and 6.9m high — angled such that the space between them pointed skywards. The outer shells were made of ceramic glass, the same material used by NASA for its space shuttles, which was apparently procured with the assistance of the United States Embassy in KL.

The sculpture fuses the artist’s traditional triangular symbolism with advanced, futuristic materials. In a way, it was a nod to Malaysian ethnography while, at the same time, looked towards the country’s future aspirations. Puncak Purnama was regarded as among the finest sculptural works situated in a public space in Malaysia.

The reasons offered by DBKL for its unilateral decision to destroy the sculpture in July 2016 was that it had become difficult to maintain. In fact, it was an “eyesore”, as infamously described by the Minister of Federal Territories at the time. However, the local art community, including Balai Seni Negara (Malaysia’s national art gallery), expressed disappointment at DBKL’s actions and failure to properly maintain the sculpture.

Its dismantling meant the sculpture stood for only 30 years. Questions were inevitably raised by conservationists and artists on the government’s commitment to preserving Malaysia’s cultural heritage, with memories of recently demolished sites such as Bok House, Pudu Prison and the Wong Ah Fook mansion still fresh.

Moving on to May 2021, Petroliam Nasional Bhd decided to shut down its public art museum, Galeri Petronas, after 29 years. Custodian of an in-depth collection of Malaysian art, Petronas decided instead to make the artworks available for loan to “relevant programmes and initiatives”. The decision by the wealthiest of all GLCs to cease the museum’s operations leaves the country with one less major supporter of Malaysian art, when funding and places available for the public to view items of historical significance are already scarce in the country.

galeri_petronas_1.jpg

This perhaps is not so consequential if the role of art is merely to look pretty. Malaysian art is more than that. Here, many artworks have become a form of documentation of the country’s history, civilisation and culture.

To be clear, a painting is not perhaps the most perfect piece of primary historical evidence, to prove something took place, but it can serve as a tool to visualise the past, the spirit of an age or even the practices of ordinary people not normally part of official historical records. In that sense, Malaysian art can lay claim to being an integral part of our nation’s institutional memory. Art in Malaysia, therefore, needs to be viewed in that context by the government, its agencies and the public in any assessment of whether it is a medium deserving of institutional support.

Largely a casual pursuit during the early 20th century, art in Malaya began a semblance of formality only in the 1930s, gathering momentum after World War II, firstly in Penang, and later in KL. This is relatively late in comparison to Indonesia, where Balinese art shaped by the Hindu-Javanese empire of Majapahit can be traced back to the 14th century. Indonesia’s modern art movement was also likely pioneered in the 19th century by Javanese artist Raden Saleh, who painted scenes of the Dutch East Indies with a certain European flair.

A likely explanation for why Malaysia’s art history began only more recently, as highlighted by scholars before, is that the British colonial system paid greater attention to developing skillsets among the locals that were useful for a career in civil administration, such as a command of the English language. Art had little to no role here.

The development of art consequently coincided with Merdeka. A succession of events several years before and after 1957 advanced the role of art, while leaders gave recognition to the possibility of art being an instrument for building Malaya as an independent nation.

img_balai_seni_1.jpg

Two art collectives, namely the Wednesday Art Group and the Angkatan Pelukis Semenanjung, were formed in 1952 and 1957 respectively. Their members produced artworks that approached a Malayan cultural identity. The objectives and aesthetic languages of the two groups were very dissimilar, reflecting the diversity of ideas and personalities even then, though both co-existed in pushing the development of art in Malaya forward.

Balai Seni Negara was then founded in 1958, and positioned as a home for local artworks that would record, mirror and fuel Malaysia’s nation-building aspirations. The accompanying publication for their inaugural exhibition, which was opened by Tunku Abdul Rahman on Aug 27 that year, states that “Art expresses and reflects the spirit and personality of the peoples who make a nation … The foundations of Independence have been well laid, and it is the responsibility of the present generation of Malayans to build on them a nation which will gain some of its inspiration from a fine collection of works of art …”. The works of Syed Ahmad were, in fact, among the first acquired by the Balai in its initial years.

Formal art education at the post-secondary level was subsequently made available, and the return of Malaysians from Europe and the US during the 1960s, having undertaken formal art training there on scholarships, also helped to establish art as a bona fide discipline here.

The establishment of two august national institutions — Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) and Muzium Negara — was marked by competitions to identify art murals that would decorate the exteriors of their respective buildings. The winning submission for DBP’s competition in 1961 was by 17-year-old Ismail Mustam, one of a trio of artistic prodigies studying at the Victoria Institution in the early 1960s who sold their own paintings to Balai Seni Negara. The others were Dzulkifli Buyong and Hajeedar Abdul Majid.

muzium_negara.jpg

The mural competition for the national museum in 1962 was won by Cheong Laitong, a first-generation Malayan who fled his hometown in Guangzhou, China, in 1938 to escape the Second Sino-Japanese War. Ironically, the Japanese invaded Malaya some years later.

Both murals — today regarded as iconic works of Malaysian art — were clearly being employed to record Malaya’s history, culture and way of life as they were perceived then. Thankfully, they continue to grace the facades of DBP and Muzium Negara to this day.

In addition, Shell commissioned Hoessein Enas, the Javanese-born artist who escaped to Penang from Dutch troops after Indonesia declared its independence in August 1945, to produce artworks that would commemorate the formation of Malaysia as a new federation in 1963. Hoessein travelled across Malaya and Borneo for this purpose, and his paintings from this commission serve as a visual record of the peoples and cultures of Malaysia in the year it was formed.

Since then, Malaysian art has gone well beyond the documentation of portraits, landscapes and cultural practices. In the last decade alone, Malaysia’s artists have produced artworks that comment on topics as diverse as the 1Malaysia Development Bhd scandal, the fallacy of GE14, society’s indifference towards corruption, urbanisation, the cult of “Saya yang menurut perintah”, the challenges facing our local Indian community, single motherhood, the Malayan Emergency and Covid-19. Even May 13 arguably had some bearing on Malaysian art in the decades after 1969.

memetik_daun_tembakau_di_kelantan.jpg

One can thus sense the passage of history and mood of the country by observing artworks produced here in the last 80 years. Malaya’s earthy landscapes and agricultural history of post-war days as captured by Abdullah Ariff and Yong Mun Sen; the early optimism of a new nation obvious in the works of Hoessein, Dzulkifli and Patrick Ng; social and environmental challenges that followed economic growth, as painted by Kok Yew Puah, Nirmala Dutt Shanmughalingam, Ahmad Shukri Mohamed and Gan Chin Lee; heightened political awareness since the Mahathir years as seen in the works of Ahmad Fuad Osman and Zulkifli Yusoff; and present-day personal trials, as produced by Eng Hwee Chu and Fadilah Karim. These are only some examples.

Puncak Purnama, now forever lost, was part of that process of documenting Malaysia’s history. Galeri Petronas too. Art is for the education and enjoyment of the rakyat, just as history is. Now, a retail outlet will likely fill the space where Galeri Petronas once occupied, while all that is left today of where Syed Ahmad’s sculpture once stood is an unremarkable patch of flowers planted by DBKL.

Azmir Zain is a director of Galeri Z, a private art museum in Kuala Lumpur, and a non-executive board member of the National Art Gallery. The views expressed here are entirely his own and do not necessarily represent those of any organisation he is associated with.

This article first appeared on June 28, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.