'Misheard' (2021) (All photos: Sculptureatwork)

Tang Mun Kian should have been in Macau. Instead, the artist and creative director of Sculptureatwork — a sculpture design studio — could only oversee his exhibition of large-scale steel installations remotely from Kuala Lumpur.

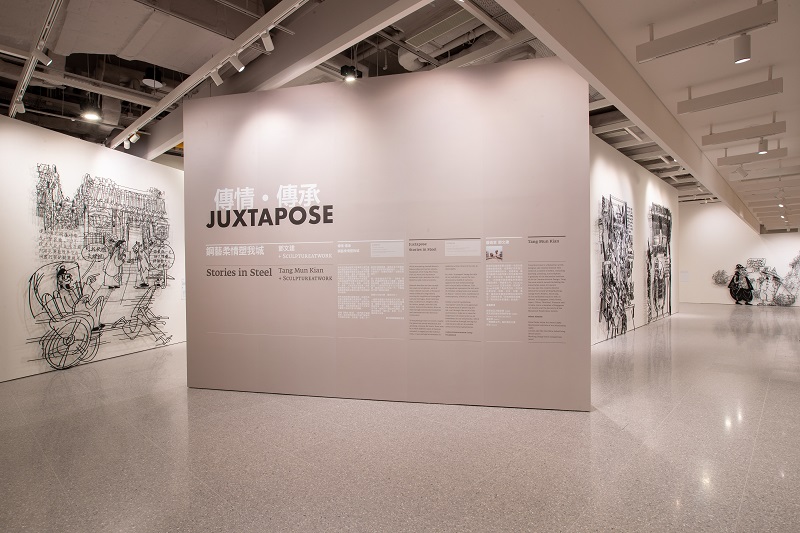

Still, it is quite a feat as Tang’s showcase, titled Juxtapose, successfully went up in July. It is being held in conjunction with the Macao International Art Biennale 2021, or Art Macao as it is popularly known, where 30 exhibitions are being held in more than 25 locations in the historical city until October.

The Biennale aims to promote Macau as a world heritage city, and has the noble intention to “reshape the humanistic spirit in the post-epidemic era”. How then did a Malaysian artist end up presenting a show that is not only in Macau, but also shines a spotlight on the small peninsula’s rich cultural identity?

The story began 12 years ago, when Tang took part in and won the Marking George Town competition in Penang, held as part of the celebration of its Unesco World Heritage Site status.

chingay.jpg

Tang, who has a background in graphic design and had spent a decade in advertising before switching to sculpture design, won for his idea of erecting steel rod caricatures with elements of storytelling on the key streets of the island’s city centre. Today, they have both literally and figuratively become a fixture of George Town’s vibrant cultural landscape.

“I wanted to make something that lasts. But I didn’t want to spoil the buildings and cityscape, since they are historical architecture,” he says on how the steel series was born. “Painting on them would risk defacing the buildings, and with the sculptures, I anchored most of the weight on the ground where necessary. It’s my way of respecting the city.”

It was Marking George Town that brought the Galaxy Entertainment Group to his door in 2019. Impressed by his work, it commissioned a steel sculpture series for Art Macao (originally planned for 2020 but postponed due to the pandemic).

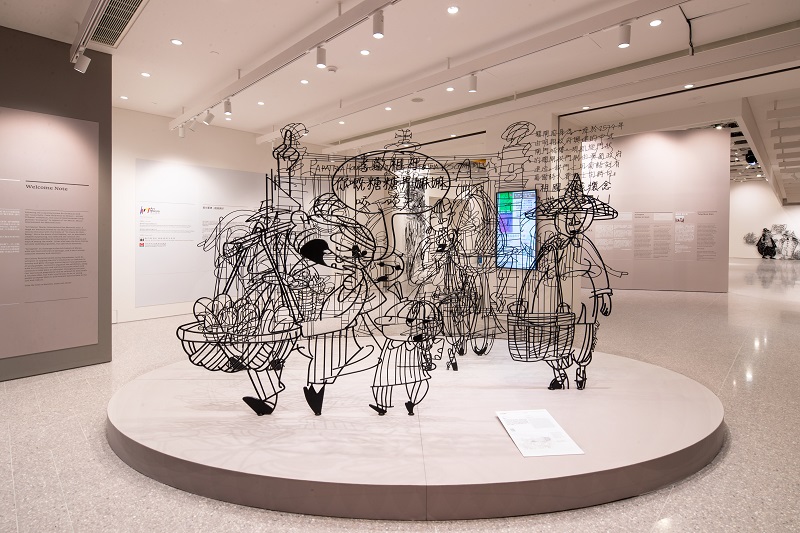

Juxtapose is the inaugural exhibition for GalaxyArt, an initiative under the group’s independent philanthropic arm, GEG Foundation. Featuring 11 steel rod sculptures sized between 2.6m and 3.6m in height, each sees Tang’s hallmark caricature cartoon style, though far more intricate than his works from more than a decade ago.

tangmunkian_1.jpg

“I wanted to do a sort of visual journal on Macau through art,” he says. In fact, the works are lifted almost entirely from a sketchbook he carried with him and in which he drew various scenes and buildings and noted down stories and historical anecdotes during a thorough walkthrough of the city in 2019.

“I walked from the top of Macau at the Chinese border, all the way down to Saint Paul’s,” says Tang. He also spent time with a local historian, which helped him to bring out colour and imaginative story elements.

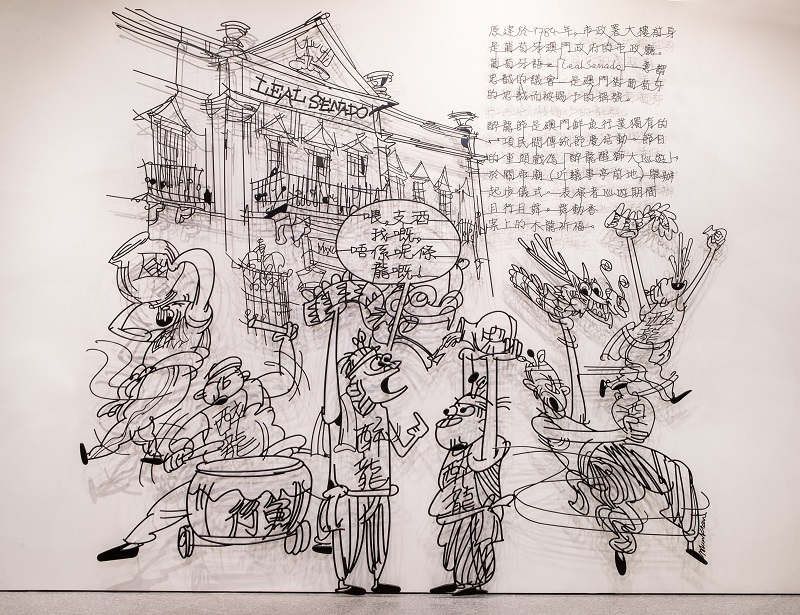

His piece on the Ruins of Saint Paul’s, for example, harks back to the time when missionaries came from the West. Tang imagines a humorous exchange between a newly arrived priest and a local maiden in Cantonese. A mispronunciation of the word “ask” resulted in an inappropriate request for a kiss instead (the words “ask” and “kiss” share the same sound in Cantonese, but with different tones). In the accompanying text, he relates a historical fact about the Ruins depicted in the background.

This format is repeated in each cartoon. In Naamyam, he highlights a traditional narrative-style singing and the famous tea house that used to have many such performances. In A-ma Temple, he relates an anecdotal account of how the name “Macau” came about — when the Portuguese first docked near the temple, they tried asking for the name of the city, but the locals thought they were asking about the name of the temple.

entrance_to_juxtapose.jpg

“Macau really is a mix of East and West, and the old and new coexist. There is the casino glamour and glitz, and then there is the historical old town. It is a contrast; that’s why the show’s title is Juxtapose,” Tang points out.

“There are two works side by side depicting the different festivals celebrated in Macau — the Feast of Our Lady of Fatima and the Festival of the Drunken Dragon. They are two very contrasting events, but both are part of Macau’s [culture and identity].”

The biggest challenge for Tang and his team was to get the works installed remotely since they could not be there. The team created an installation guide for local contractors. Still, he seems to have nerves of steel, taking it all in stride.

Sculptureatwork, which mainly takes on commercial commissions, has made its mark all over Malaysia and beyond with its public artworks, ranging from a giant guitar at the entrance of Hard Rock Hotel Desaru Coast and the more colourful mosaic version at the Hard Rock Café in Melaka to the abstract “Little India Dancers” metal sculpture in Brickfields, Kuala Lumpur.

The brains behind most of these works, Tang explains his creative process. “The city is like my paper. I walk around and find places to put my pieces.”

drunken_dragon.jpg

Having gone from advertising to commercial work and also pure art, the creative director is comfortable working with different mediums and materials. He is also not fussed about whether people would view his work as art or just commercial design. “I think it’s almost the same thing,” he says.

Tang admits that he doesn’t fit the fine art mould. “I think art is part of business; you need to sell your art to make more art. We don’t live in Van Gogh’s time.

“I have artist friends who are stuck because they know the art they do doesn’t sell. I think in this case, they don’t have the freedom to do art actually. It’s not sustainable.

“The ecosystem of collector, curator, gallery space — if one of these breaks, the whole chain breaks, as we can see, especially in this pandemic.”

candy.jpg

Having said that, he may be more of an artist with a temperament than he lets on. “I don’t like to deal with curators or clients, so I mainly focus on the art side of things. My mind is split into two actually,” he continues. “I have a brain for clients, where I need to meet their brief, but I like the challenge of working within the box and rules. You still have the freedom to solve problems and push boundaries.”

As our conversation comes to an end, a mixed media painting hanging on the wall behind Tang comes to my attention. It’s very much a gallery piece, both visually and in substance — a personal rumination on his family’s past, his history, identity and the questions he has around it. “This is for myself,” he notes. “I made it as an outlet for me. It started when I thought back to my grandpa’s time, of when he came from Canton, China. That’s all I know of his story. It just stopped there, and I wanted to know what happened at the time.”

One cannot help but draw a parallel to Juxtapose, of our innate desire to look back to the past, to hear its stories and perhaps find resonance, or something, anything, that can carry us forward from the present, even if it is in a simple, cartoon form that fuels our imaginations.

'Juxtapose' will run at GalaxyArt, Galaxy Macau, until Oct 31. A virtual show can be viewed here.

This article first appeared on Jul 26, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.