Miyashita is an esteemed interior designer with Culture Convenience Club Co Ltd, which operates Japan’s biggest book chain Tsutaya (Photo: Patrick Goh/The Edge Malaysia)

As photography creates a past while capturing a frame of the present, architecture is turning the needs of people today to design for a better tomorrow. From a young age, Yoshiaki Miyashita has developed a keen eye for the unusual, as his lensman father would take him around their hometown of Kanagawa, Japan, to capture life or places that often went unseen. Now an esteemed interior designer with Culture Convenience Club Co Ltd, which operates Japan’s biggest book chain Tsutaya, Miyashita seeks to give lacklustre buildings character by curating a strong design identity from within.

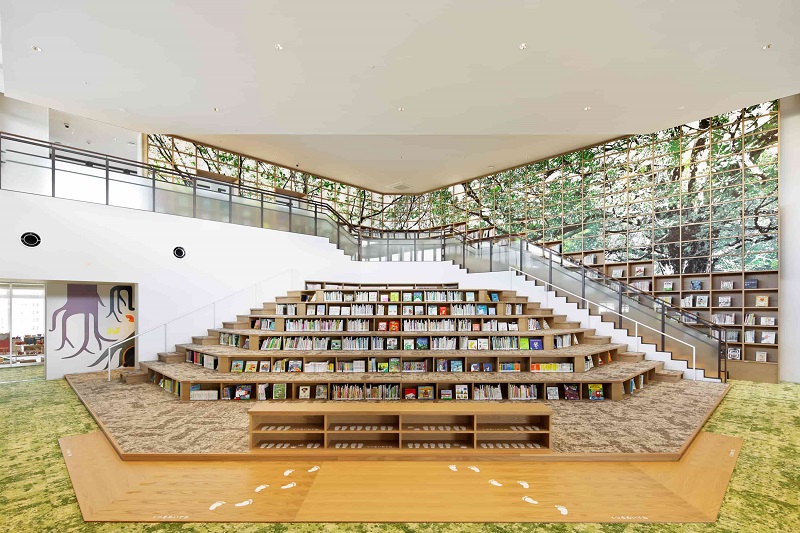

Although one of his most ambitious undertakings includes the rejuvenation of the Wakayama Civic Library, in which a public complex was transformed into a thriving community hub and the lifeblood of the town, his popular works still revolve around creating memorable spaces for Tsutaya Books. His interpretation of the Nara outlet is not as lofty as, say, the latticeclad flagship store at in Shibuya especially designed by Klein Dytham Architecture, but it pays heed to the needs of the local community while retaining the prefecture’s historic charms.

wakayama_civic_library.jpg

American architect Louis Kahn’s monumental and brutalist style captivates Miyashita’s imagination just as much as the visual spectacles fashioned by fellow Japanese interior designer and furniture maker Koichi Futatsumata, whose famous creation Restaurant on the Sea has conjured up a rich discourse built around food on Teshima Island.

“Mastering a rapport between nature and artifice is a skill I really admire,” says Miyashita, who also derives inspiration from travelling, such as visiting Kyoto’s Tofukuji Temple and art epicentre Paris. “Ever conscious of the power of natural landscapes and the importance of spatial quality, these visionaries know when not to intervene.”

tsutaya_nara.jpg

Spend enough time at a Tsutaya bookstore, and such a scene will grow familiar. For the 31,000 sq ft Pavilion Bukit Jalil store, which can accommodate at least 240,000 books, Miyashita rids his designs of extraneous visual clutter to devise an effective floor plan that guides customers along their intellectual journey. A floor-to-ceiling feature shelf at the entryway communicates the concept of space and human scale to anyone who enters.

Despite the mall bookstore being a public domain, it harbours the warmth of a home with private nooks to linger or chat over a cuppa. In keeping with a marketing-free and minimalist aesthetic, the bestseller section does not scream hard sell, while the wood-based furniture stays in a modest palette of unassuming earthy tones. So soothing and meditative is the Japanese omotenashi (the philosophy of wholeheartedly looking after guests) that you will not be blamed for thinking that the store wants to politely bow for your patronage.

tsutaya_bukit_jalil.jpg

With the onslaught of e-commerce and digital reads, a community-driven brand like Tsutaya could be the plot twist in the ongoing narrative to revive physical bookstores. “People think we’re suffering from losses because they can read for free. But that’s not the case — a lot of them end up buying the books they browsed because they want to finish them at home. Moreover, by becoming part of the local fabric, a bookstore has evolved into a gathering hub to connect the like-minded,” Miyashita says.

For a word that suggests as little as possible, minimalism in Tsutaya’s dictionary conveys a bigger ambition: To cultivate freedom of thought and amplify voices without the noise. Soon, we will be going into Tsutaya Books in the hope of seeing our favourite author read or whiling the day away with yet another Murakami epic (Miyashita is a fan, by the way). Bibliophiles, it’s a date.

This article first appeared in issue No. 104, Summer 2022 of Haven.