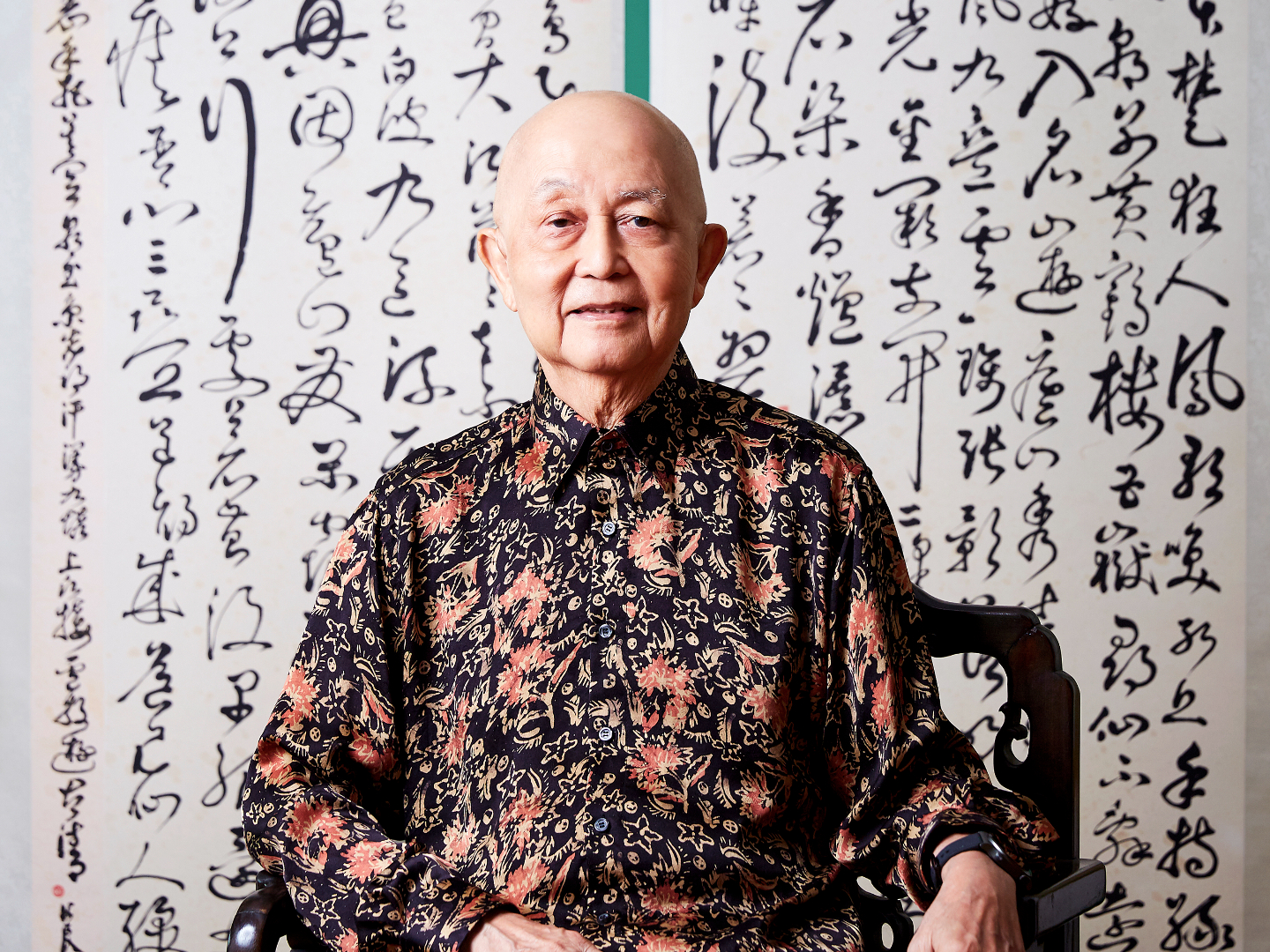

Chooi has carved a fruitful career, even as he dedicated himself community and public service (Photo: Soophye)

I turn into a quiet but narrow cul-de-sac in an affluent part of Kuala Lumpur, and after parking in a designated spot through an open gate, I walk up the short flight of stairs of a rather unassuming home and knock on the door. A voice calls out and then the door opens, and Chooi Mun Sou, founder of Chooi & Co and one of Malaysia’s most distinguished veteran lawyers, welcomes me himself into his living room.

“We’ve lived here since 1969,” says Chooi as he gestures at the space. The first thing I notice is the beautiful Steinway piano, the only showpiece in an otherwise warm and cosy home lined with artworks and mementos. Chinese watercolour paintings hang alongside calligraphy works by Mrs Chooi, colourful and bright small frames painted by his second daughter, Penelope, and photos of family and friends.

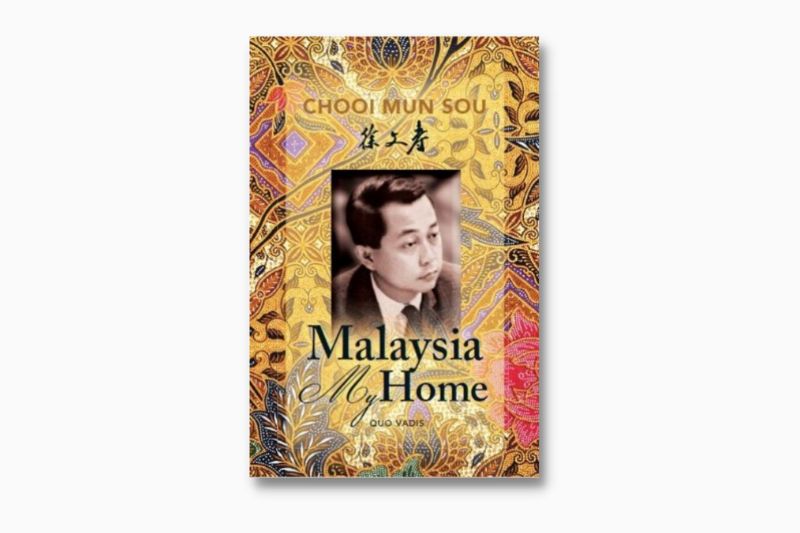

After a short introduction to some of these items he particularly holds dear, we sit down for a chat about his memoir, Malaysia My Home, an epic personal recounting that spans more than eight decades: from British Malaya to the Japanese Occupation; the road to independence; and the birth and growth of a nation.

To call it just a memoir may be a disservice, though. Factual, rich in detail, yet concise, the book offers a valuable alternative narrative of Malaysian history in its charting of key events and milestones, and introduces the who’s who that have shaped the nation, with its heroes, villains and all in between.

chooi_mun_sou_-_malaysia_my_home.jpg

Far from being a bystander, having been right in the middle of the action from the birth of Corporate Malaysia to its growth spurt, Chooi was an instrumental player in the local banking industry, and an early member of the local legal fraternity. Through these lenses and more, he relates the ups and downs with remarkable clarity and flair, and not always in the way we think we know our history.

Just how did you remember it all, I ask? “I had notes for some events, and with the Bumiputra Malaysia Finance (BMF) one, I already had a full account. But, for the rest of the events that went on, I just could remember them,” says the 83-year-old with a smile.

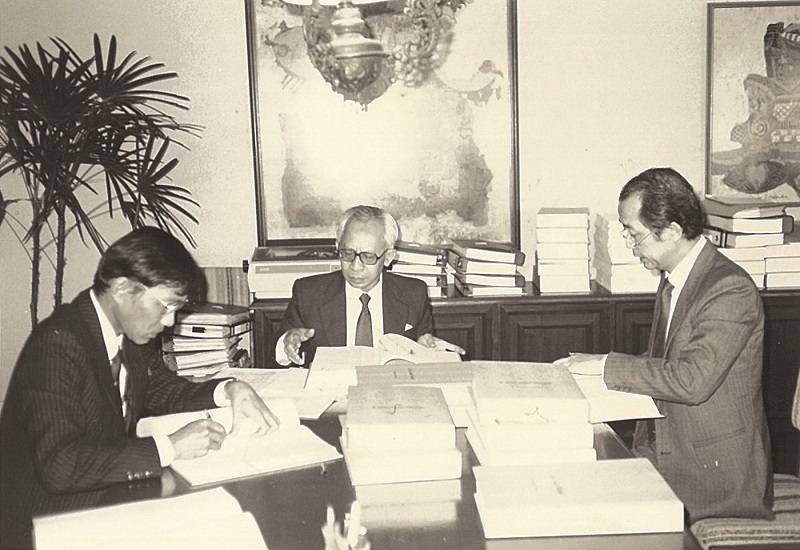

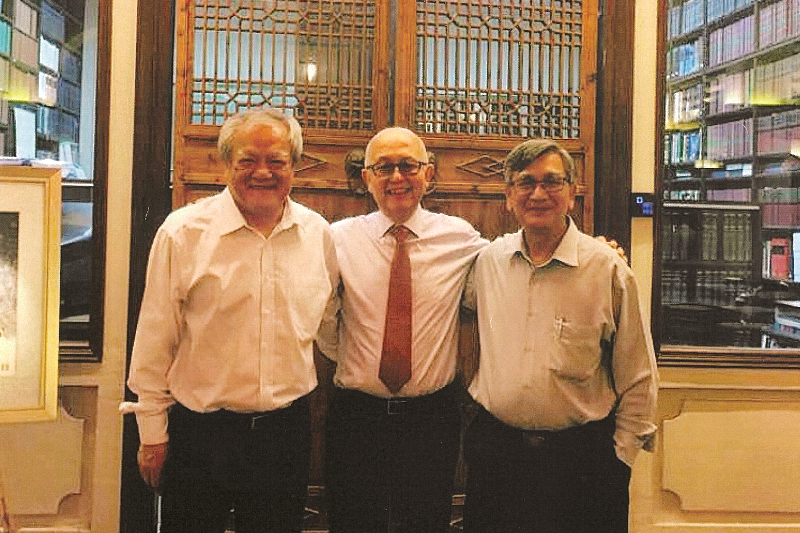

The BMF scandal was the catalyst for the book. It was then the largest financial scandal that rocked Malaysia and Hong Kong with a loss of up to RM2.5 billion in the 1980s, and Chooi became most well known for being part of a three-man committee of inquiry appointed by then prime minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad. It marked entering a long-drawn-out battle to investigate and expose what truly happened and those involved, as well as being caught in the crosshairs of politics, though by dogged determination, the investigators eventually did see some justice served.

“After the BMF report was completed in 1986, I decided that while it was fresh in my mind, I would write a behind-the-scenes account of how we investigated the whole saga. I finished it in four to five months, but nobody dared to publish it,” recounts Chooi.

“Macmillan’s Hong Kong had wanted it, and were about to start work when London stopped them. Perhaps because, at the time, Dr Mahathir was fighting with Margaret Thatcher, for political reasons, they probably didn’t want to [stir the pot]. Plus, there was a risk that the book might be banned. So, I put it aside.”

photo_21_a.jpg

But Chooi would continue sharing his story at seminars and talks until 2013, when 1Malaysia Development Bhd (1MDB) surfaced. He decided then that the BMF story must be documented, albeit late. Asked why, then, he paused. “I think it’s the love of my country,” he says measuredly. “And that’s why I ended up calling it Malaysia My Home.”

Rather than concentrating just on BMF, he decided that he would start the story from when he was born — on the last day of 1938. The writing process would take him a while, with the first draft completed just before the 14th General Election in 2018. “The first person I showed it to was [Datuk Seri] Kalimullah [Hassan]. He advised that it was too technical, so I revised it,” says Chooi. “The onset of the pandemic prolonged the editing into a few years.”

There were other speedbumps along the way, including a health scare in 2020, followed by a landslide that took out the back wall of his home during the December rains last year. But the veteran lawyer remained unfazed, as is his nature when he has set his mind to something.

“In a way, it’s good. I was able to do more revision in the last few months and I took out all the parts that I felt weren’t really necessary, but as some writers would say, it is ‘sexy’ — people enjoy reading things like that. Still, I do not want to sensationalise things that do not hit at my main thrust of the story,” says Chooi, who was also vigilant about details to include or omit, and who or how the stories may affect or implicate.

Asked whether there were chapters that were difficult to write or reflect on, his answer is no. On the contrary, owning up to his mistakes was not difficult at all to do. Chooi refers to a disastrous outing he had as a relatively inexperienced lawyer eager to be known.

cover_pix.jpg

It was his “Moment in the Desert”, as he titled it. Having been offered a directorship at the doomed Southern Cross Airways and enticed by the chance to join other prominent figures such as the then chairman of the Stock Exchange of Malaysia and Singapore, David Hebdige, as well as Tan Sri Hanafiah Hussain, then tipped to be the next Finance Minister of Malaysia, it seemed a chance not to be missed.

“I got carried away. My mistake was I kepoh (stuck my nose in) and organised a loan for them with my good clients, OCBC Bank. When it went wrong, although as non-executive directors we were not liable, Hebdige wanted to pay the claim by OCBC, which argued we were acting as guarantors. It was designed to embarrass us. I said I would pay my share as well, which was a quarter of the sum,” recalls Chooi. It would be years before OCBC retained Chooi & Co again.

Nevertheless, there were a few paragraphs that were particularly emotional to write. In 1966, on a Sunday afternoon, Chooi lost his one-year-old son Christopher when he accidentally fell from his cot. His voice softens, “I was so happy when he was born, I have a daughter and a son now; it’s complete. When he fell, the doctor living next door to us was away playing golf, and another one across the road was not in. Somehow, they got my brother-in-law to come to me. I was in the office working, but when I rushed home, he was dead. I buried him and carried on working.”

It was only 14 years later, during a spiritual retreat in Port Dickson, that Chooi came to terms with his grief. “I had taken my son to Port Dickson before. And when I was meditating on Christ, my son came to mind. He was walking and someone was holding his hand. In the vision I saw, they both turned and waved at me, and it was Christ and my son. I cried and cried, totally wrecked. The next day, the same image came, but this time waiting for them were my parents.

“Only after that could I talk about this incident, like I’m sharing with you now. Before that, I wouldn’t talk about it,” he admits.

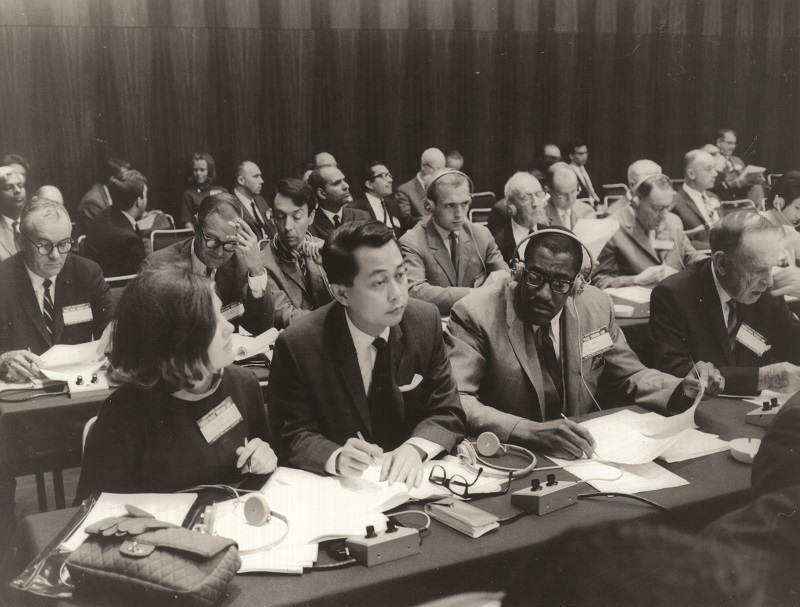

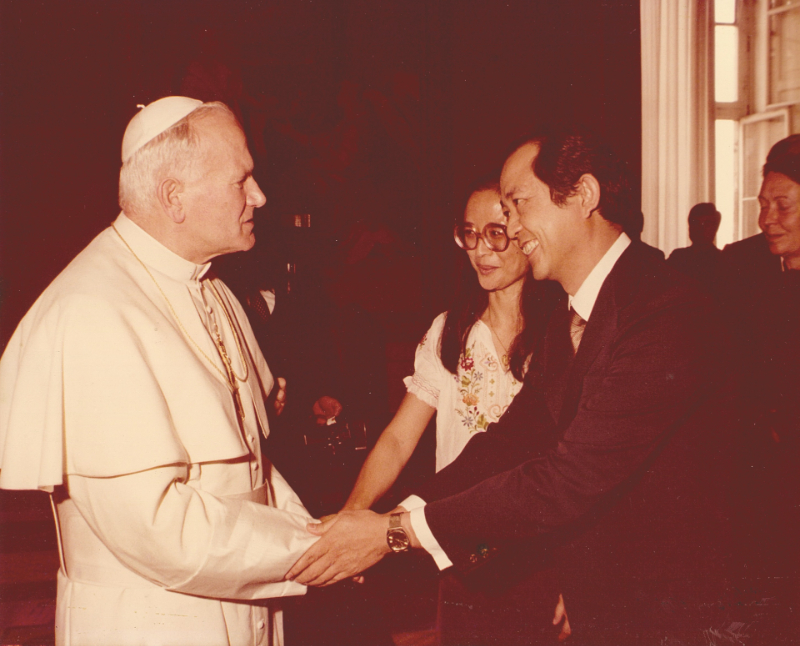

photo_22_a.jpg

‘Just do the right thing’

One of the things that underlines Chooi’s life and story throughout the book is his Christian faith — first as a Methodist and later a Catholic.

During his recollection of the BMF inquiry, at one point when the trio had to decide whether to publish the report and antagonise Dr Mahathir and cause a political uproar that could cost their individual careers, Chooi wrote, “I did not hesitate. When I accepted the appointment almost two years ago, I was clear I would carry out my responsibilities to the very end.”

He continues: “I remember that moment. I had emphasised that I was only answerable to one person, my Creator.” In response, Tan Sri Ahmad Nordin Zakaria, the former auditor general, who was the face of the BMF inquiry, replied, “We have the same God.” Chooi says it was a poignant and beautiful moment amid a daunting task. They decided to publish the report.

Perhaps anyone who has crossed paths with him can attest to a strong-headed tendency to stand his ground no matter the obstacle or temptation. And there have been many, especially in his field of specialisation in corporate and banking. “Many times, I can only laugh when they come to me and say, ‘Mr Chooi, we trust your reputation; you don’t have to do anything as stakeholder.’ And, then, when I query the legal process, true enough, there’s a lot of siphoning off of money through various means. These are huge sums! I would calculate my legal fees, and it would be in the millions, just for putting my name down. I send them on their way.”

His advice to lawyers today? “Just do the right thing. You can always cleverly twist anything to suit yourself, but you just have to be pure at heart. And when it comes down to it, throw down your pride — often, it’s really that.”

photo_30_c.jpg

A true-blue KL-ite, Chooi had an upbringing that was, for the most part, comfortable and well protected. Born in Jalan Raja Chulan (Weld Road) after which the family moved to Jalan Kamunting, off Imbi Road, where the Tun Razak Exchange now sits, Chooi studied at the Methodist Boys School (MBS), followed by a short stint in Victoria Institution (VI) before travelling abroad — for the first time — to read law in the UK in 1957, the year Malaysia declared its independence from British rule.

“I was pampered, having been protected even through the war,” acknowledges Chooi. Sharing another anecdote from the book, where he is approaching the end of his secondary school life, he says: “I played Mark Antony in the school play, but then scored three zeroes for my science exams after.”

Needing a transfer from MBS to VI but unable to get his headmaster to endorse it because of his results, he decided to approach the secretary of education of that time and got the letter he needed to transfer. “I would do things like that ... It’s always been my nature,” he says.

It is a nature much suited to legal practice. One that enabled him to set up his one-man legal firm at just 24. Even before that, though, while working with Balwant Singh, a lawyer known for his criminal practice, Chooi had eagerly sought out his own cases. “I remember at age 22, I did my first murder trial.” It was a sad case involving an 18-year-old who killed her own baby. She had pleaded guilty, but he was able to ask for leniency.

“Nowadays, when I talk to a pupil and suggest he take on a bigger case, he says, ‘No lah, Mr Chooi, I can’t.’ What on earth!”

His tone is, nonetheless, one of affection. As a veteran lawyer, Chooi and his firm have trained some of the country’s brightest lawyers. Even this writer, a former law student, was a beneficiary of his broad network and willingness to extend a hand — having helped secure an internship with a London-based solicitor through an intermediary, unbeknown to me till much later.

photo_27.jpg

If there is an underlying theme to his memoir, it would be one of public service and civic duty. Besides starting up the Malaysian Bar Council’s legal aid, Chooi to this day does not charge for legal services rendered to any religious organisations, be it Hindu, Buddhist, Christian or any other faith.

Professionally, he also had a key role in shaping the Housing Developers’ Association, known today as Rehda, and started the Bar Council’s journal for lawyers, INSAF, among many more.

During the Malaysian judicial crisis in 1988, he was entreated to address the legal fraternity when then Lord President of the Federal Court Tun Salleh Abas was sacked, along with a few other judges. Chooi spoke frankly of his belief that the dismissals were not justified.

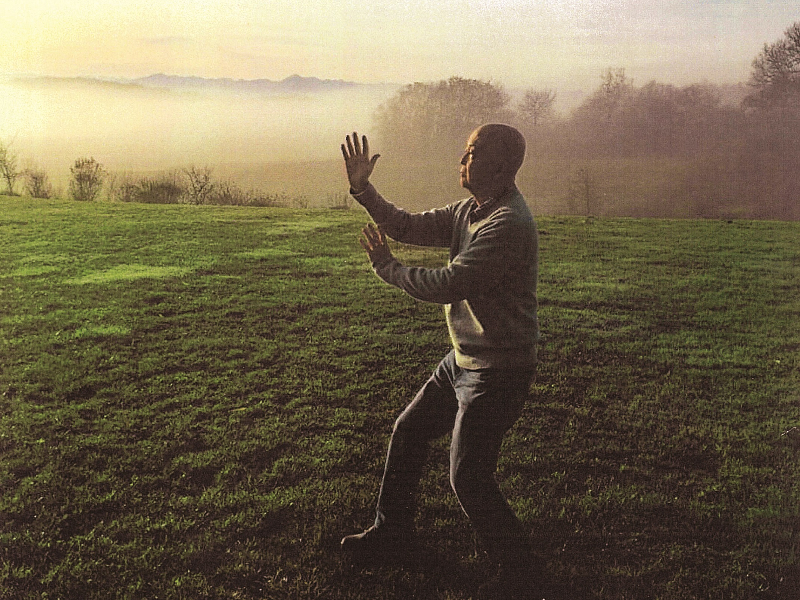

His firm, now named CCA after a merger with Cheang & Ariff, another law firm led by Datuk Loh Siew Cheang, will celebrate its 60th anniversary this year. Although he has stepped down — for the second time in 2007 as managing partner — Chooi still goes to the office every morning on weekdays after his kungfu practice, and in the afternoon when necessary.

“Retirement? No, no, that word doesn’t exist for me,” he half-jokes. “I help with administration, I interview pupils if necessary and if any of the lawyers need to come and see me — whatever needs to be done.”

While Chooi speaks honestly and boldly in his memoirs against the poison of corruption and critically examines the political direction that has ruled Malaysia since its independence, in the end, he remains hopeful for the future of the country.

“Trust [God], and do your part,” he emphasises. He follows up with this advice for young lawyers and Malaysians in general, “What needs to be done, do it!”

This article first appeared on July 25, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.