During the launch of its sustainable sub-brand, Coachtopia, Coach embedded each item with a unique digital ID powered by tech company EON to drive full lifecycle transparency (Photo: Coach)

Shopping, with its promise of endless visual variety, has become a widespread pastime, an addictive activity that is a constant presence much like a wonky zipper that keeps getting caught or the stubborn pills gathering on your favourite sweater. While numerous fashion labels have surely urged many of their customers to rethink the speed at which clothes are made, consumed and discarded, it is hard to accept, with a straight face, that their proposition of looking cute is a way of saving the planet.

This is not an article to discuss, again, the inescapable buzzword that is sustainability or malign the image of brands, which prey on our aspirations and insecurities, conditioning us to believe that our garments should be abundant and new. This is about how the birthplace of fast fashion, stemming from a voracious appetite for cheap and trend-driven clothing, is finally making moves to end it.

We can no longer afford the luxury of ignoring the cycle of consumption perpetuated by fast fashion. Therefore, by 2026, every textile product for sale in the European Union (EU) will require a digital product passport (DPP) that may take the form of a scannable QR code, NFC chip or tag. Once accessed, the DPP will provide information about the life of the product, such as details on its composition, manufacture, supply chain, sustainability, recyclability and possibly much more — all assembled under one place from various federated sources.

The lofty ambition, as envisioned by the EU when it backed a raft of new regulations and made DPP part of its Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles, is to alleviate the deleterious effects of 12.6 tonnes of textiles wasted each year in the EU alone. The benefits of the DPP, a digital twin of the physical product, are twofold: First, brands will see it as a way to add value for customers making a long-term investment in, say, a heritage bag. Second, they can be part of a broader effect to push for greater transparency in industries operating in Europe.

coach_explain.jpg

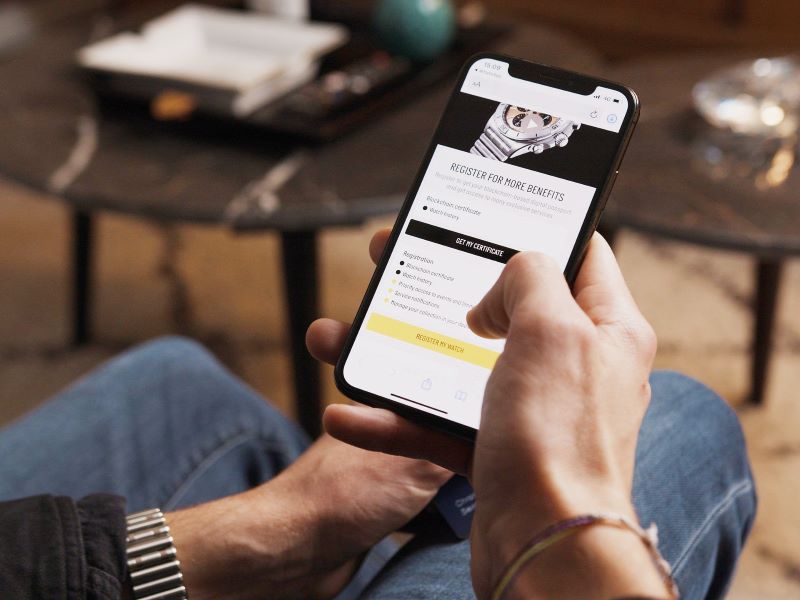

A few fashion houses have, in fact, begun exploring the potential of digital IDs, which enable customers to authenticate products, transfer ownership and access an array of services such as resale and repair. It is just that the impending EU rules, which are expected to end the industry’s longstanding culture of secrecy, have accelerated these efforts and created a sense of urgency as companies are starting to think about how they can be in compliance.

For example, in 2021, a cohort of luxury maisons comprising LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, Prada Group and Cartier teamed up to create the Aura Blockchain Consortium, a nonprofit association of 30 member brands exploring how blockchain technology can be used to, among other things, break the code of silence on their supply chains. Recently, Arianee, a platform that provides identifications for avant-garde haute couture house Mugler, created more than 1.6 million DPPs, with 10 brand partners — all watchmakers including those from luxury goods powerhouse Richemont — on track to have 100% of their new products covered by mid-2024. Eon, a cloud-based New York start-up, empowers Coach, Chloé and Mulberry to create an ecosystem that will allow their management to keep tabs on their wares post-sale.

Mounting pressure for accountability has also prompted prominent names such as Breitling, IWC Schaffhausen and Panerai to make big strides in implementing DPPs to reveal the source of their raw materials. In case we forget, many brands are secretive for a very different reason. Certain watchmakers may be reluctant to admit their “Swiss Made” watches contain components manufactured outside of the country. While this is not strictly a legal concern, Swiss law dictates that at least 60% of the manufacturing cost of a product must be incurred in the country for it to qualify for the coveted label long associated with quality, precision and value.

arianee.jpg

Let’s take a breath here. Now, how much do consumers, despite their best efforts to invest in products that will outlast them, actually care? Consider this reality: Why are people paying more for a better-made product if they are ingesting it, but less concerned about what they drape over their shoulders? This could be due to the ease of traceability. Following the journey of an apple is relatively easier, of course, if a farm is small enough to do everything itself. Knowing where your silk blouse comes from before it reaches the store shelf, however, involves learning about the designer, silk-weaving factory, cut-and-sew process, dye house and silkworm hatchery. The fashion supply chain is so convoluted, its many moving parts spread out over so many countries and complicated processes, that the origins of our clothes seem almost entirely opaque.

But all this, as the EU aspires, is going to change when you can read a fashion label like a digital ingredient list. Luxury goods, compared with a RM50 sweatshirt purchased from a fast fashion chain, arguably make the most sense as candidates for digital identities because they can have multiple owners in their lifetimes — there is clear value in giving shoppers a means to authenticate them and discover their full history. In the end, this prolongs a product’s longevity and keeps it in circulation for much longer.

A blockchain-enabled DPP solution has carved out a future where every customer will feel connected to the story behind the products. But more importantly, brands should build on such technology and introduce extra features to encourage people to continue to scan. If they partner a local artist to create a song exclusively for a campaign, but only people who scan the DPP can listen to it, widen the music’s reach by making it shareable across various media. Highlighting a good cause that supports underprivileged artisans? Build a scannable microsite to direct people towards making a meaningful contribution.

Sustainable fashion is an oxymoron — you cannot perpetuate an industry that is ever-evolving and hope that it is able to continue or “sustain” over a period of time. Call it semantics but the term to use, perhaps, is “responsible fashion”, in which all players, from consumers to CEOs of large conglomerates, take responsibility for their part in the supply chain step by step, decision by decision. Maybe, when you fling open your wardrobe doors in the future, understanding the origins of your washed-out T-shirt or rediscovering an old necklace worn a new way, may remind you of the many kinds of fashion pleasures that exist beyond image-making and instant gratification.

This article first appeared on Apr 15, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.