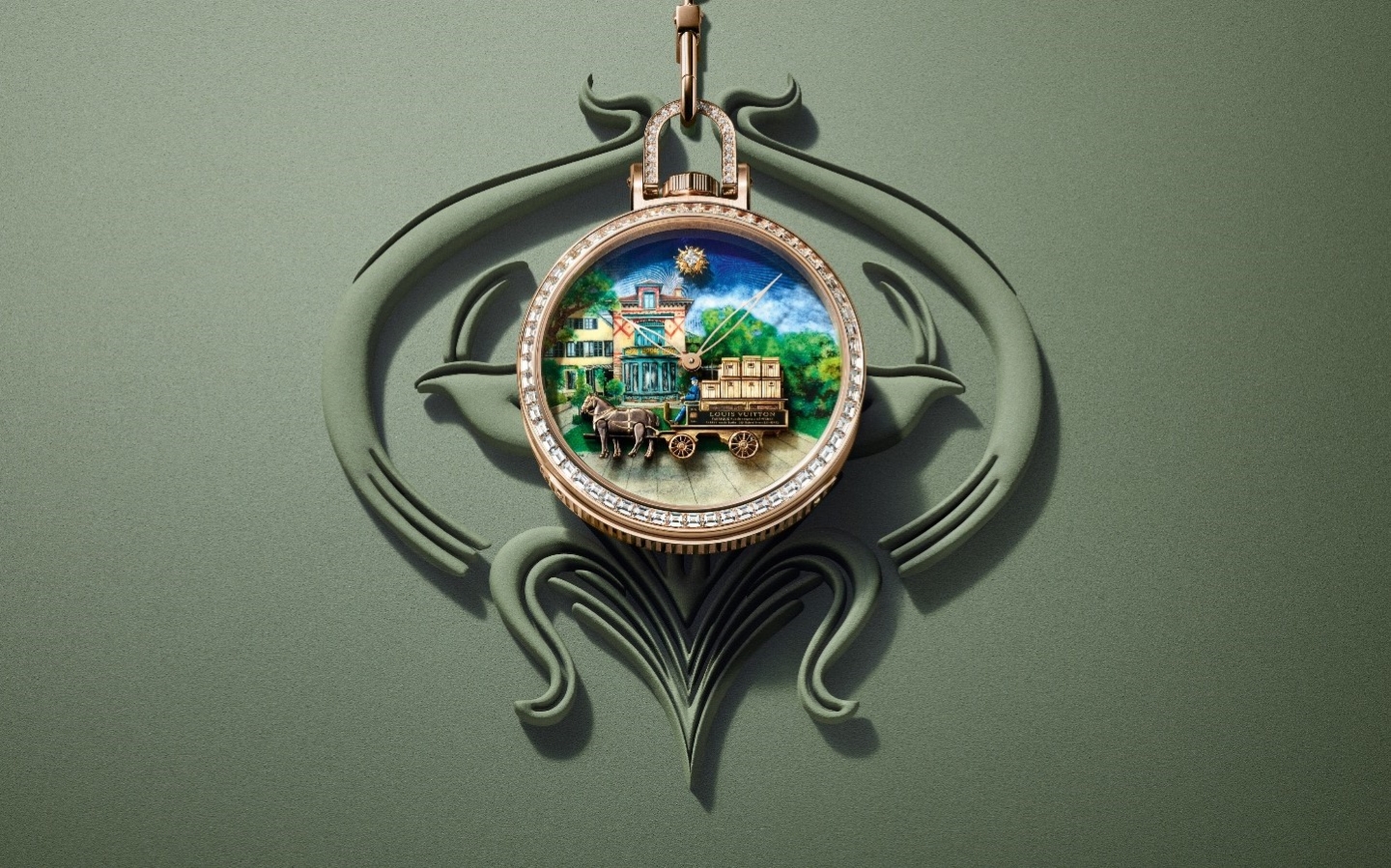

Louis Vuitton showcases its mastery of fine watchmaking with its first pocket watch, Escale à Asnières (Photo: Louis Vuitton)

Mention fashion watches, and you will likely be greeted with an eye roll or two from watch collectors and aficionados. The term is rather controversial in horological discourse and often used derogatorily to indicate frivolous timepieces made for the sole purpose of stamping a brand’s name on yet another product.

The popularity of fashion watches skyrocketed after the Quartz Crisis, as nimble players such as Swatch, Guess and Fossil shifted their priority from accuracy to aesthetics in the 1980s. Yes, quartz watches are reliable, energy-efficient and much cheaper. But the new narrative dictates that they be fashion accessories, and one can never have too many.

Side note: Contrary to popular belief, Swatch is in fact not a portmanteau of “Swiss watch” but “second watch”. And coming out of a time when owning multiple timepieces was rare, its accessible, eye-catching, non-serious and ultimately expendable products naturally generated repeat purchases in the mass market.

Fashion houses, too, recognised this opportunity and followed suit, creating new status symbols with little horological value by licensing their valuable emblems. It was often this practice that left a bad taste in the mouth of serious collectors as the art of watchmaking, its time-honoured traditions, craftsmanship and know-how had all but become secondary. Fortunately, such is not the case today.

ho2024_1112_rgb.jpg

Several brands have doubled down on their efforts to compete in the horological arena and are investing some serious money to stay in the game. After acquiring G&F Châtelain in La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1993, Chanel steadily expanded its portfolio by buying minority stakes in independent high-end watchmaking brands Romain Gauthier and FP Journe. They also acquired a 20% holding in Kenissi, the movement maker partially owned by Rolex that is also responsible for some of the calibres at Tudor, Breitling and Tag Heuer. In August, the French powerhouse announced it had taken a 25% stake in Maximilian Büsser’s MB&F.

“We are delighted to sign a strategic partnership with MB&F who share the same values of independence, creativity and excellence. The announcement is part of our long-term strategy to continue to preserve, develop and invest in specialist know-how and expertise, reaffirming our position in high-end watchmaking,” says Frédéric Grangié, president of Chanel Watches & Fine Jewellery.

And they have the products to prove it. The fashion world’s design-first approach has given birth to some of the most arresting pieces of our time. Chanel’s gender-fluid J12, inspired by the world of yacht racing, was arguably the most coveted watch in 1999 when it launched. Back then, ceramic was not nearly as common in watchmaking as it is today. In addition to its standout design, the J12 was something of a revolution and remains a steadfast symbol of the brand.

08-lv-escale-pocket-watch.jpg

Louis Vuitton is not one to rest on its laurels either, and with Jean Arnault, the youngest scion of the LVMH empire at its helm, the brand is looking to shake things up in the horological universe. The acquisition of La Fabrique Du Temps in 2011 — a high-concept movement manufacture founded by the renowned watchmaking duo of Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini — and specialist dial maker Léman Cadran (2012) are perhaps some of the most important milestones in Louis Vuitton’s bid to secure its supply chain.

Since then, the maison has released an array of timepieces (most notably the redesigned and utterly handsome Tambour), earned a handful of Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève (GPHG) awards and established the Louis Vuitton Watch Prize to acknowledge and celebrate the work of extraordinary independent watchmakers.

Through the years, Louis Vuitton has unveiled some remarkable timepieces, from tourbillons to automata, to highlight its horological mastery. This can be observed from the recently released Escale à Asnières, its very first pocket watch. The Escale à Asnières pays tribute to the savoir faire and unique history of the legendary trunkmaking workshop, Asnières, and of course, La Fabrique du Temps.

Housed in a 50mm 18-carat pink gold case, a minute repeater movement and automata mechanism of seven animations are enhanced by outstanding métier d’arts including gold engraving and enamelling. Taking elements from an 1887 Louis Vuitton advertisement and a portrait of three generations of the Vuitton family at Asnières from 1888, the foreground depicts a 19th-century horse-drawn delivery carriage stacked high with its famous trunks.

hermes_cut.jpg

And what about Hermès? In 2006, the luxury leather house acquired a 25% stake in Vaucher Manufacture Fleurier, which supplies mechanical movements to the world’s most prestigious watchmakers, including Audemars Piguet, Richard Mille and Parmigiani Fleurier. Its first proprietary movements — the H1837 and H1912 — rolled off the production line at Vaucher in 2012.

In the following years, the brand also acquired dial maker Natéber from La Chaux-de-Fonds and case manufacturer Joseph Érard from Le Noirmont. Both sites were eventually integrated to become Les Ateliers d’Hermès Horloger (2017). From then on, the watchmaking department started to truly take off. First impressions of the 2019 Arceau l’Heure de la Lune and the 2021 sporty H08 are still fresh in our minds.

Hermès is clearly no stranger to masterful craftsmanship and impeccable design. What it brings to the world of watches is distinctive, playful and of the highest order. Its novelties this year have successfully captured the hearts of many, but the Hermès Cut, which sold like hot cakes the moment it went live, heralds a new chapter for the maison.

There is more to the Hermès Cut that meets the eye despite its pared down aesthetics and time-only function. It is sophistication packaged in a design inspired by simple shapes and essential lines. The brand describes it as a circle in a round case — its flanks are shaved off ever so slightly to create a refreshing new visual. Equipped with the self-winding Calibre H1912, the versatile watch comes in a unisex 36mm with a variety of iterations as well as strap and bracelet options.

In this day and age, it would be foolish to pigeonhole all fashion brands as producers of run-of-the-mill watches when there are clearly some that are raising the bar in so many aspects of horology. The design-forward perspective of these houses gives them an edge — an approach in which few traditional watchmakers are willing to entertain — and play a part in enriching the horological landscape we know today. Diverse input will serve to make the industry better and more accessible, ultimately pushing the limits of watchmaking for generations to come.

This article first appeared on Sept 16, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.