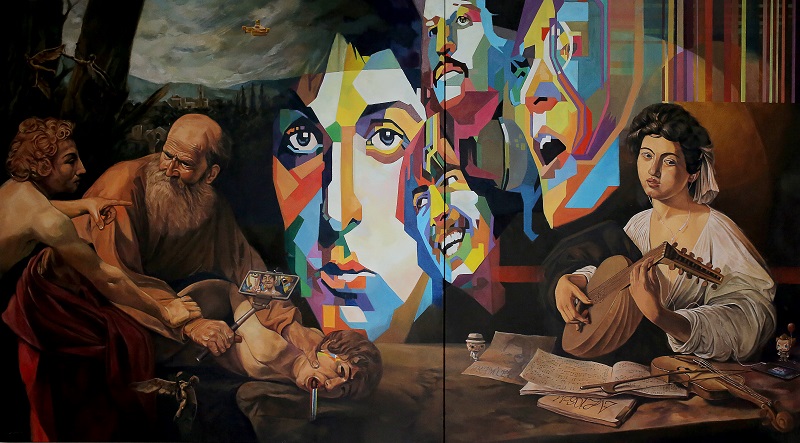

Ali posing in front of Great Festival, which was acquired by the National Art Gallery (Photo: Sam Fong/The Edge)

Walking into Gallery Reka, it feels like we are entering the Old Masters’ wing of a European art museum. That is, until we see artist Ali Nurazmal Yusoff staring out at us from a large painting facing the entrance.

He is Ali, the puppet master — one of the many characters he “plays” in his artworks. The piece, titled Great Festival (2009-2010), is the curtain-raiser to a show orchestrated, directed and acted in by the artist himself. Welcome to Project A: Last Man Standing, a mid-career exhibition by one of Malaysia’s more intrepid artists.

While the 42-year-old has had a prolific career spanning over 20 years, the show focuses on his Imitation Master series — a body of work centred on imitating artists such as Caravaggio, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo — which started with After Caravaggio (2009). That painting transformed the Universiti Teknologi Mara (UTM)-trained painter from an abstract artist into one equally adept at figurative work.

ali_nurazmal_yusoff_imitation_master_after_caravaggio_oil.jpg

“I like to say that I work in the in-between,” says Ali, who is suave and has the confidence of a Renaissance man. His varied interests and talents, as well as keen sense of observation, weave their way into his paintings, which are rich with layered symbolism hidden in plain sight.

Therein lies the crux of the Imitation Master series — there is much to be discovered underneath the obvious. Curator Benedetta Segala, who coincidentally hails from the same hometown region as Caravaggio, explains: “Ali started with imitating the formalistic style of Caravaggio’s realism work, and it gets close to the master’s. But, at the same time, the narrative and perspective is really Malaysian — it’s also his own. His own interpretation is very strong, always humorous and personal. That makes it very interesting.”

Some of the works in the series have strange and funny scenes. In Time and Space (2013), Jesus is wearing a Manchester United shirt while eating durian and reaching for some petai. The shape of an iPhone button — that on the older models — is marked on the side, denoting the larger theme of how technology brings the world closer, drawing a parallel also to bridging the past and present.

ali_nurazmal_yusoff_imitation_master_after_caravaggio_time_and_space_oil_on_canvas_153cm_x_330cm_2013.jpg

The keys to decoding Ali’s symbols lie in understanding what makes the artist tick. A work right by the entrance offers the first hint. East Meets West (2014) depicts a Malay man — Ali’s actor friend — holding a keris in a stand-off with Western figures.

This tension between East and West forms the subtext of the series. In Letter For Mona (2010), Ali depicts his wife next to the famed Mona Lisa, wittily questioning the standards of beauty. From social-media culture to pop culture and, more subtly, politics, the artist draws a juxtaposition of the West and our local context. A work titled Yellow Submarine (2016-2018) features the Beatles, a 16th-century figure playing P Ramlee’s Getaran Jiwa on the lute, and another holding a smartphone while filming.

“He transforms 15th- and 16th-century Caravaggio into something contemporary, attracting today’s viewers into that world. Once inside, you’ll discover many things. It’s like a library,” says Segala. “The symbolisms teach us how to engage with things that look so different, to increase our curiosity and the elasticity of the mind. Ali’s work inspires people to be more universal.”

ali_nurazmal_yusoff_imitation_master_yellow_submarine_oil_on_canvas_153cm_x_275cm_2016-2018.jpg

There are those who may ask, “Why imitate?” When put to the artist, who has an exuberant personality, he admits to loving a challenge. “In art school, they say the most complex form is figurative and it’s hard to paint. So, I wanted to show that I could do it. While practising, among the artists I referred to was Caravaggio and I particularly liked how he handled the painting itself, how it feels alive with the play of light and shadow, and how he created a theatrical ambience.”

The last remark offers another clue. Last Man Standing is not just another exhibition of paintings. For Ali, it is the realisation of a decade-long dream he had painstakingly worked to achieve. “As a painter, these are my artworks. But as an artist, this whole show is my artwork. Ever since my first piece in 2009, I imagined creating a museum-quality show, right down to this lighting,” he points out, alluding to his performer’s nature. “It’s about an idea. I didn’t just paint — I rehearsed it. I cultivated an attitude and a lifestyle around it.”

He has a name for it — Alism. It is a sort of branding for his artistic approach, and was first coined by his lecturer and fellow art students at UTM, who questioned why he went against the grain and created his own “ism” in a class assignment that required him to use a formal technique. His reply to them was, “Why not?”

ali_nurazmal_yusoff_networking_oil_on_canvas_122_cm_x76_cm_quadriptych_2012_1.jpg

When Ali’s father asked him to observe an apple and draw it as a young boy, he did so but also started redesigning the apple. “I painted it blue once and my father said, ‘You can’t’. But why not? I want to sell this idea of possibility.” Apples have become a common symbol in his works.

In After Caravaggio II (2012), a baroque-style marketing meeting takes place, with apples in the centre of the table as the product. For Networking (2012), a quadriptych, the apple becomes the lure for climbing the social and economic ladder, aiming for the ultimate top rung — Zeus. What does the apple represent? Draw from it what you will, be it a bribe, a promise, an impression or even a lie.

If there is any cynicism in his observations of the ways of the world through his work, Ali is coy about it. “I am just a moderator,” he says. At least, he acknowledges the irony of his imitations. “We learn these techniques, from art to business to politics even, but now is the time to start developing our own way.” In a way, it explains his most recent piece, Nasi Lemak Spaghetti (2020), which shows the Malaysian offering a nasi lemak packet to Caravaggio’s fortune teller.

Still, Ali insists he’s not here to preach which way is better. “It’s not about what is good or wrong. It’s about accepting it, seeing what it is, how to learn from it and expand it.”

'Project A: Last Man Standing' is being held until July 30 at Gallery Reka, National Art Gallery, 2 Jalan Temerloh, Titiwangsa, KL. Admission is free.

This article first appeared on July 13, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.