Volvo’s Vision 2020 is to reduce the number of deaths or serious injuries in accidents involving Volvo cars to zero (All photos: Volvo)

It was Christmas Eve. Anna, Martin and their children were driving along snowy roads to the grandparents’ house to celebrate. The mood was festive — the older brother teased his twin sisters that he would receive the biggest gifts and they all wondered when Santa Claus would come that night.

About an hour plus into their journey, they saw a car coming towards them, looking like it had lost its grip on the road. “Then, it went black,” recounted Anna. “And suddenly, we woke up in a ditch. Then, the screaming began. The children thought mummy was going to die.”

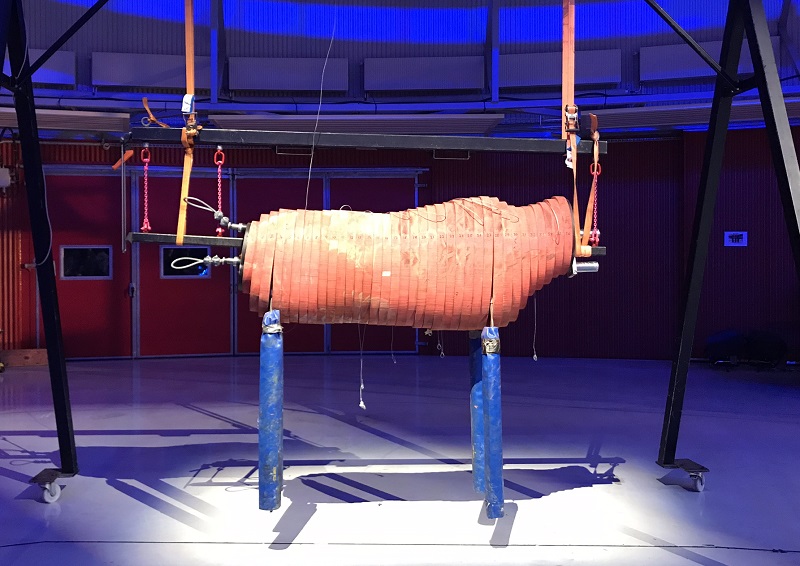

She and Martin were standing on a platform in a warehouse in Gothenburg, Sweden, as they shared their harrowing experience that fateful day two years ago. “The ambulance people said they didn’t think anybody was alive in that car … being so close to death, you realise anything can happen in a matter of seconds. I definitely enjoy life a lot more now,” she said softly.

Their story set the scene for the main event — the unveiling of Swedish carmaker Volvo’s vision for car safety in the years to come. International media — including Options as the sole Malaysian representative — were invited to gather at the marque’s home base for its Safety Moment campaign launch, where key figures from its technical as well as research and development teams took to the stage one by one to lay out the company’s blueprint and aspirations in a carefully orchestrated presentation that was as inspiring as it was deliberate.

CEO Håkan Samuelsson started off with a reminder of the 60th anniversary of the three-point safety belt this year, a Volvo invention that the company chose not to patent, but rather to share it freely with other automotive manufacturers.

The belt is but one in a long list of firsts for Volvo when it comes to safety innovations. Highlights include the recommendation of rear-facing child seats in 1972, followed by the advocacy of a safety booster cushion for children aged four and above in 1978, which led to the introduction of integrated booster cushions in Volvo cars in 1990.

Other crucial innovations include the Side Impact Protection System and airbags, Whiplash Injury Protection System for seats and head restraints, roof-mounted inflatable curtain to provide extra head protection and, in more recent years, the “city safety” auto-brake system and run-off road protection with energy-absorbing seat functionality to prevent spine injury.

In some ways, the Safety Moment event was an anticipated one, considering the closing in of the deadline for Volvo’s Vision 2020 — a bold commitment to reduce the number of deaths or serious injuries in accidents involving Volvo cars to zero. In fact, a couple of weeks before this grand exercise, the company caused a ripple by announcing its plans to impose a 180kph speed limit on all its cars from next year.

As Samuelsson continued his introductory address — no doubt most in the room were eager to further question this unprecedented speed limit — we were curious about what else the carmaker has in store.

But in the same spirit of generosity as the three-point safety belt and more, the CEO announced the company’s new project, the EVA — which stands for “Equal vehicles for all” — Initiative.

EVA is a central digital library which shares reports and post-analysis data from years of safety research. This site is open to industry peers and the public alike.

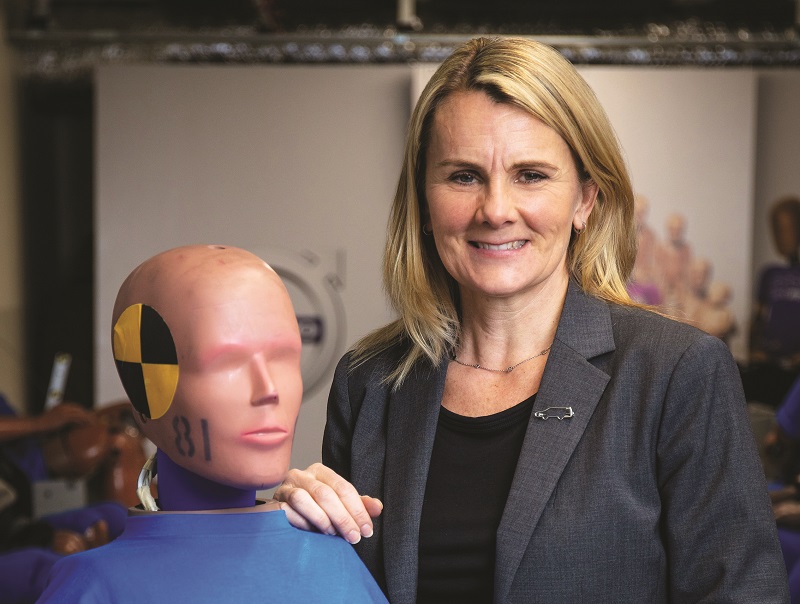

On the initiative, Lotta Jakobsson, senior technical specialist at Volvo Cars Safety Centre, said at the heart of Volvo’s “innovation after innovation” is a working method based on real-world data, which it has collected since 1970, collated and worked on by its accident research team, who have carried out research and investigations “24/7, round the year” for more than five decades.

“Based on data of these tens of thousands of accidents involving Volvo cars, we’ve developed our safety technologies. The idea of sharing knowledge and innovation with the industry and research community goes hand in hand with how we work. We want the rest of the industry to do the same — trying our best to make cars equally safe for all people, irrespective of height, weight, gender or shape. Obviously, real-world data is the best way to [achieve] that. It goes beyond merely relying on standardised crash-test dummies, which come in limited sizes,” she said.

The human factor — three major risks

One key phrase that kept coming up during conversations with the various specialists was something that Samuelsson laid out from the beginning. “In order to move forward with the vision, we have to shift our attention to tackling the crux of safety issues — the human element,” he noted.

More specifically, the term used was a “human-centric” working method which underlies all that the company does, and which led to how it arrived at three categories of driving safety risks to contend with in order to make zero deaths in accident a reality. These are speeding, distraction and intoxication.

“We’re not stopping at the speed cap,” declared senior technical adviser of safety Jan Ivarsson. Admitting that the company had “stuck out its necks” by introducing the 180kph speed limit for its cars, he, nevertheless, expressed confidence that in time, this will become another industry standard.

“Not everyone is positive about this,” he smiled knowingly. “Some said it is a sign of weakness if a car can’t safely go more than 180kph, or that speeding has nothing to do with safety, that ‘when I’m driving faster, I am sharper and pay more attention to the traffic’,” he recited, drawing a parallel to the response of the three-point safety belt 60 years ago. “They said then that you had a better of chance of surviving if you were thrown out of a car than if you were strapped with a seatbelt. They said being strapped scared them …”

But how did Volvo arrive at 180kph as the limit? Surprisingly, it was just a case of picking a reasonable number. Volvo Cars Safety Centre technical expert Mikael Ljung Aust said the figure is not as important as it is about having a mindset about the right speeds on public roads, especially in environments such as school areas or suburbs. “Beyond a certain speed, we really don’t have any business to drive that way on roads. There are just too many variables. The other half of the equation is that, from our research, accidents happen when we run out of time. Driving is about adapting to your surroundings all the time and sometimes, we don’t have time to adapt or react. We want to support you by giving you time back when you need it most,” said Aust.

Besides imposing the speed limit, what is also set to be a standard feature worldwide from next year is the Volvo Care Key, which allows the owner to set a speed limit for himself or when he lends his car to somebody.

The team at Volvo state that, in the end, their goal is to prevent accidents altogether, rather than limit their impact. According to their analysis, losing focus while driving is another issue that causes accidents — be it due to distractions or intoxication.

On that note, we found ourselves in a stationary XC90 with eye-tracking cameras hooked up within to detect and chart our eye movements. It offered a glimpse of the smart cameras that the company promises will be in the next generation of its scalable product architecture platform cars — comprising larger models such as the S90, V90 and V90 Cross Country as well as the XC90 itself.

Volvo Cars Safety Centre vice-president Malin Ekholm said, “The cameras read your eye movements to ensure you preserve vision and attention on the road. Through this, we can understand your coordination while driving, analysing it to ensure that you have sufficient steering and brake reaction times for critical situations that may arise.”

However, with this the question of driving intervention and over-reliance naturally arises. Ekholm emphasised that the function will only help when needed and is there to encourage our natural desire to be good drivers.

“There will be no intervention, say, as soon as you take your eyes off the road. We focus on extreme behaviour that may lead to serious injury. For example, if the car detects a complete lack of steering input for an extended period, or if the cameras notice that you are looking away or closing your eyes for a long time, or slumping in your seat, it will give warnings and activate brake and steering corrections. If they do not have an effect, someone from Volvo Call will ring and ask how you are doing,” she said.

The final step the team is working on is a full intervention that involves bringing the car to a complete stop and parking it by the side of the road. In line with that, the carmaker is also exploring automatically slowing down the vehicle in specific areas, such as near schools, by using GPS technology.

Well aware of the potential implications and even alienation of customers, Ekholm said the team are vigilant about not creating new safety issues in their quest for increasing driver support. “We need to find that right balance between support and over-reliance. Our systems need to be there for you when you need them, not for you to use them and not be responsible for your own driving.”

As Volvo levels up on its crusade for safety — embracing its founders’ vision for the protection of those behind the wheel, and not just the machine — the company said realistically, this is just a conversation starter. If that’s the case, we can only hope that others will join in soon.

This article first appeared on June 3, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.