Parmjit also talks about optimisation as a secret to his success (Photo: Soophye)

The business of education is not easy, but APIIT Education Group (under which sits the Asia Pacific University of Technology & Innovation or APU) co-founder and CEO Datuk Parmjit Singh has found out how to succeed: Get your clientele right. This does not mean shopping at the best possible schools for potential undergraduates, which in turn assures top-scoring graduates in four years — pimply, awkward teenagers are not the goal here. On the contrary, Parmjit considers his clients the tech giants that will one day hire his students, and he measures the university’s success by how well it can produce industry-savvy graduates who then become highly sought-after professionals.

Indeed, the employability of the group’s graduates now run as high as 300%, with some students juggling multiple job offers well before obtaining their qualifications — the man is definitely doing something right. As he takes Options on a tour of the university’s vast facility in Technology Park Malaysia, we are more than impressed by the high-tech classrooms and advanced computer studios that students have access to, including the country’s most sophisticated cybersecurity research lab.

Parmjit’s drive to provide high-quality education and an employable future at competitive costs is very personal — these were opportunities he and many of his contemporaries were denied in the post-New Economic Policy years, when strict quotas meant that many who qualified for a place in public universities could not get one, no matter how deserving they were.

apu_cybersecurity_talent_zone.jpg

“I didn’t get a place; neither did the rest of my siblings. Although my dad was a professional — he was an engineer with TNB — we saw him struggling to send us all to university overseas,” Parmjit recalls. “Private tertiary education in the early 1970s was only for dropouts from the school system, those who were not eligible for university — so it was limited to low-level vocational courses. But we were looking for a university education and there was nothing available back then as it exists today.”

The second child in a family of six, Parmjit postponed furthering his studies overseas because of money, or the lack thereof — his father was already under pressure to fund his older brother’s medical degree. But the sprightly young man had an entrepreneurial streak and went on to make his own money trading stocks. “My father used to tell his friends that if he gave his older son a dollar, he would walk home empty-handed. But if he gave me just 20 sen, I would come back with a dollar,” he laughs.

Parmjit was very successful until the oil crisis of the mid-1970s — “it was worse than anything you’ve seen today” — at which point, he truly understood what dad had said about getting an education. “Money comes and goes, but your degree is yours forever,” he smiles. “So, I went to the UK, which I funded myself, driving cabs while studying computer science. But I never forgot how my dad and his friends struggled to support their children in university. It came to the point where families had to choose which of their children could go to university. To me, this was unacceptable.”

Thus was sown APU’s principles of a good education for all, although it would be many years until Parmjit was able to establish his technology and innovation institute back home in Kuala Lumpur.

After completing his degree Parmjit got a job with European tech giant ICL, and when it established a training centre in Singapore, he took the opportunity to be closer to home. It was while working with ICL’s centre at Ngee Ann Polytechnic that he realised there was something to be said for graduates who were not only academically qualified but also professionally trained and ready for the corporate environment.

64612139_10157348895292566_1486757282321530880_n.jpg

“The focus of the project was more competency-based and geared towards training graduates to be highly applicable to industry,” Parmjit recalls. “Its blueprint was amazing, and I got very excited because even what I studied was more theoretical.” Upon moving to KL soon after, he became part of a similar set-up for ICL, whose clients back then included Keretapi Tanah Melayu and the Employees Provident Fund. The training centre did well and many of those who went through the system were hired by ICL. Competitors tried their hand at the market but simply could not replicate what ICL was doing.

One morning in 1992, however, it all went to hell. Fujitsu had conducted an overnight raid of the London Stock Exchange and acquired controlling shares of ICL, and since its motivation was to take over the European giant’s technology, the training centre was of no interest to it. Parmjit could not afford to buy it over, so he leaned into his entrepreneurial spirit and set up what was the Asia Pacific Institute of Information Technology in 1993 with a few partners. The first of its kind in Malaysia, it acquired university status in 2006, becoming APU.

It was a decision that would change the course of his life, and that of the tertiary education industry in Malaysia, for good. He started small but strong, and was never ashamed to get down and dirty. In the early years, it was Parmjit who would take on cleaning toilets, mopping floors, making coffee and even driving his pioneer batch of female students home after night class. No job was too small for him, such was his passion for the business. Its guiding principle was inspired by what he had learnt at ICL — graduates need to be ready to get to work.

“The principle of industry-ready graduates has always been in place right up to this day,” he says. “We are the largest tech-based university in the country, beating Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Universiti Malaya and so on, and employers are in search of our guys. Everything we do covers academics but it is also highly practical. For that reason, all our lecturers have industry experience. The definition of our client is not the student because we are not here to please them — it is the industry, so our focus is different. My vice-chancellor has only one KPI (key performance indicator): 100% employability of all our graduates. Our public universities don’t define themselves like this. For them, the onus is on the employers to train the graduates. I find this to be [rubbish].”

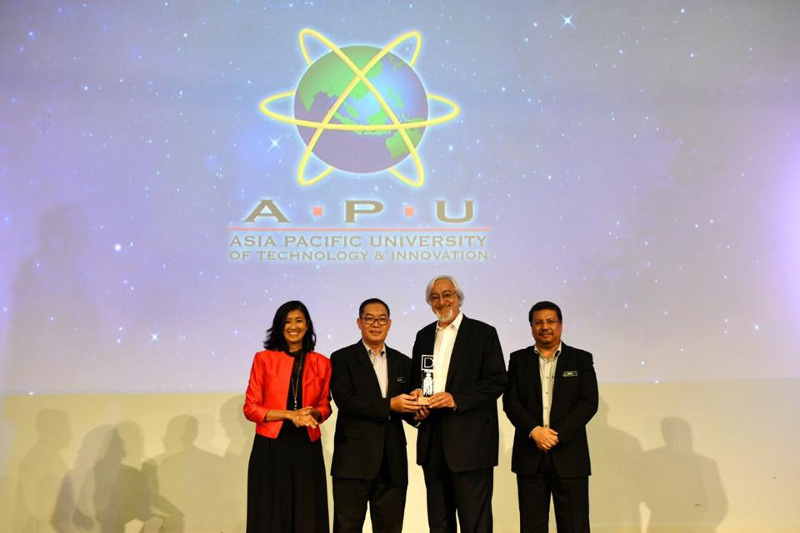

This is probably the sharp-shooting, straight-talking stuff that secured Parmjit, who is in his early 60s, his recent success at the EY Entrepreneur Of The Year Malaysia 2021, where he emerged overall winner and champion of the Master category. EY is in fact APU’s auditor and had for years encouraged him to participate in the initiative; it was only because his team put in the application without his knowledge that he was considered — and is now representing Malaysia in Monaco.

20220329_213016.jpg

Something that few people may know about the EOY programme is its gruelling interview process, which sees an independent judging panel ask nominees tough questions about their business — sound financials are easy to prove, but what about vision, direction and ethos? Each nominee must have thought about these well beforehand and worked out how to articulate them well. One can imagine how the charismatic Parmjit, with his clear voice and impressive sweep of silver hair, would have made quite the impression. But his is no lip service, as the educational institute he founded 29 years ago has proved to be extremely successful over the years. The APIIT Education Group has evolved into one of the nation’s leading enterprise in the industry and a globally recognised brand, boasting a portfolio of more than 100 academic programmes and more than 13,000 students. Today, APU’s global footprint extends to more than 130 countries, attracting more than 6,000 international students.

Not thinking like a typical university is critical to Parmjit’s leadership of the group — from the manner in which it embraces courses with a high barrier to entry to the way all the lecturers must come with vast industry experience. “Our courses are 70% engineering and tech, 30% business-related. Where other universities may be afraid to go in, we go in deep — this asks for massive investments in infrastructure, which we aren’t afraid to make. Employability goes up when you do this! For example, we are the largest producers of cybersecurity graduates in the country. You have to have a corporate culture that attracts and retains the best possible industry experts to teach here. We do not operate like an academic institution and that is very important. All my vice-chancellors are from corporate environments in MNCs (multinational corporations). So, they bring that culture here.”

Indeed, doing things differently has worked out well for him, it must be said. This even includes not having a secretary — no one in the company does. “We are a tech university. If we can’t rely on technology to help us manage our day, then what do we even stand for lah?” he quips. But the man has a point.

apu_cybersecurity_talent_zone_1.jpg

Just then, freshly made mugs of coffee arrive for us courtesy of Valli the F&B assistant, whom Parmjit greets warmly by name. After a quick exchange with her, which we notice was as respectful and personal as it would have been with a senior associate, he says thoughtfully, “In this company, no one is any bigger than anyone else, everyone is equally important, everyone is replaceable. Some years back, I embarked on a five-year plan that would properly flatten this organisation and make it more efficient. I completed this transformation well within my five-year target, and it’s built so that even if I were to walk away tomorrow — which I am not planning on doing, of course — the university will continue to run. The only thing I think that will be missed is the guidance and support I provide my team. But I am confident that in my absence, there may be others who will step up to do this.”

Parmjit also talks about optimisation as a secret to his success — he hates waste of any kind, he says, and believes in making the best use of a particular asset.

“I believe in being fully optimised — if you’re not, you will lose money,” he notes, tapping the table between us for emphasis. “This business is like any service environment, be it airlines, hotels or restaurants. Actually, let me tell you why [Malaysia Airlines Bhd] is losing money — it is our partner by the way, so the pilots who come here agree with us. When you run an airline, your most expensive assets are the planes and the staff. You must learn how to rotate staff efficiently without slave-driving them, and you must sweat your planes. Planes on the tarmac don’t make money; only those in the air do. But the ones in the air make money based on loading. Good loading — that is, many passengers — comes from a good reputation. Airfares are secondary; if people like your airline, they will fly with you. It is really that simple. There is no reason why any airline today cannot survive. It is a matter of balancing the use of your assets.

“My most expensive asset, which takes up 90% of my expenditure, is my staff force — salaries are RM5 million a month. The second is infrastructure. We operate 50 weeks a year, but the kids don’t study 50 weeks, it is just that the intakes are scheduled so that the campus is used as much as possible. The labs are utilised at incredibly high rates too. And you really have to sweat those assets very quickly because tech stuff goes out of date fast and needs to be changed. Our computers get redeployed, so nothing is discarded or thrown away. There are 1,600 machines here. Everything runs at optimum levels.”

mabacademy.jpg

Parmjit leans forward in his chair, clearly excited about this line of discussion. “Our utilisation rate sits at 90%. In universities in the UK, it is only 40%. When you shut down for the summer holidays, you don’t sweat your assets. Summer holidays were necessary in agrarian societies, which doesn’t apply anymore. Why can’t you have three intakes a year, which puts the kids in the classes quicker? At any one time, we are catering for 11,600 students. We have a sophisticated system that changes the class schedules around each week, so we get maximum use of teachers, labs and classes, with a team of five people managing it and overriding it when human intervention is necessary.”

Much of this asset-sweating could not quite apply during the pandemic, when students were forced to study from home. But the transition was easy for them. While some educational institutions might have taken weeks to adjust, APU required no more than a weekend. But rather than look at assets during this time, Parmjit and his team focused on people — he sent all of APU’s foreign students home to be with their families, ensuring each one was dropped off at the airport on the university’s tab (at least half of APU’s student body is international).

He also established a hardship fund for students whose parents had lost their jobs or taken a massive pay cut, simply because his main objective was that every student who arrives at his doors has to finish his or her education — cost should not be a factor here.

“The one thing I don’t like in this job is collecting money, because none of my students are rich — the rich send their kids overseas! What’s left are the lower-middle-income group and perhaps a portion of the B40. I don’t think anyone comes here comfortably paying fees — perhaps a small 5% to 10%. By and large, every day, I get requests for help. We look at every case and do what we can. Should something happen to the family of any student who starts with us that causes finances to become an issue, we will do something — waive fees or offer discounts. No matter what, each student finishes his or her education here.”

A successful business cannot run without heart, and it is clear that Parmjit has infused his operations with just that. The EOY win comes just as APU enters its 30th year of operations, a momentous occasion for any organisation, let alone one in the challenging arena of tertiary education — and that too in the tech space. Of all the awards that Parmjit and APU have received over the years, the accolade from EY best reaffirms his ethos as an entrepreneur.

“You know, my guys put the nomination together and submitted it without even involving me. One day they told me, ‘You have an interview with EY.’ I asked, ‘Eh, why now?’ And that’s how I found out,” Parmjit laughs. “But upon reading the submission they put together, I was so pleased to know that what I believe to be true about this company is what my team believes in as well, and that’s very gratifying. For me, that’s what this is all about.”

This article first appeared on June 6, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.