Culture and history have always interested Jones (Photo: Mohd Izwan Mohd Nazam/The Edge)

The question “what if ...?” is a prompt that Carol Jones uses to imagine plausible scenarios as she plots her novels. What if a young Chinese girl were to jump into a pair of blue trousers and take her twin brother’s place on a ship packed with migrants headed for the gold rush in Australia? What if a young man stumbles upon a secret that sheds light on his late great-grandmother, sweet 16 and in love in 1930s Malaya, who was sold as a concubine to a rich old man?

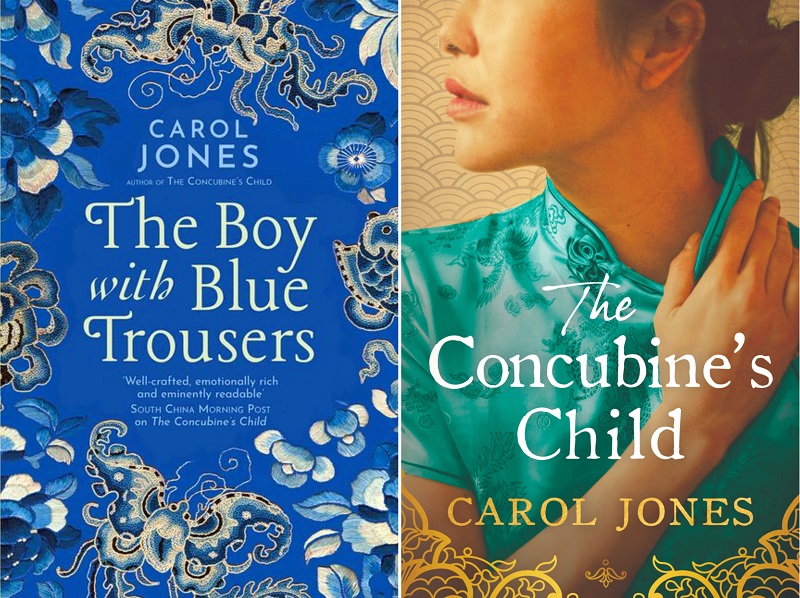

Fact seeds fiction, which Jones then frames with imagination, as evidenced in her two books, The Concubine’s Child and The Boy with Blue Trousers, published by Head of Zeus. Meticulous research fertilised her stories as she followed the what-ifs, from smoky temples to tropical jungles and abandoned ghost houses, or past the Pearl River Delta and on to a tiny town bordering Victoria, where golden promises lay.

Growing a novel is a creative process of inventing new parts as you go along, Jones shares. “Like I always say to people, just go bigger. If something happens in a story, take it one step further; make it bigger.

carol_jones_books.jpg

“I think part of imagining is innate — I love using my imagination. The other is that because you read a lot, you exercise your imagination. It is like any skill: You exercise it and it improves.”

Born in Brisbane, Australia, but resident in Melbourne since high school, Jones has spent every Chinese New Year except one in the last 29 years with her Malaysian husband’s family in Kuala Lumpur.

“One of the things I’m most interested in as a writer is where cultures meet,” the mother of two, who turns 63 this month, said during her latest sojourn. “I think that’s because I grew up in Australia and, you know, we’re a very mixed sort of bunch. I’m fifth-generation Australian and my ancestors, basically farmers, came from England, Ireland and Germany in the mid- to late 19th century.”

Culture and, inextricably, history have always interested her, hence her appetite for historical fiction, which she reads a lot of and likes to write about.

“But the research has to be very authentic when you’re writing about a culture in a time that’s not your own. Even if you’re fairly familiar with a culture you’re not born into, you can easily get something wrong. So, you have to be very careful with your research and fact-check everything.”

From non-fiction to history

In her previous incarnation as a writer of children’s books — which was how the former English-cum-drama teacher started writing, after 10 years of editing children’s magazines for the education department — Jones wrote numerous non-fiction titles for young readers on Australian history and the culture of the Pacific nations, as well as young adult fiction. Marriage to a Malaysian with a Chinese background then generated an interest in Asian history that has taken her from familiar ground into new territory.

Research has been her faithful guide, pointing out interesting things as she went along, such as polygamy being a way of life before, and even now, and men having concubines.

carol_jones_young_adult_books_1.jpg

“I wondered what it would be like for a young woman forced into one of these arrangements and whether the first wife would resent her. It struck me there was bound to be a power play that might sometimes end in tragedy.

“In a lot of cultures, the senior woman in a household can be quite vicious. Historically, it’s about maintaining their power. I’m interested in the power dynamic between women, and between men and women as well” — hence the germ for The Concubine’s Child, “a bit of a ghost story”, she says.

Jones’ research for the historical novel also unearthed articles about the “self-combed women” of Southern China in the early 20th century, who took a vow of celibacy, choosing independence over marriage. They went out to work and some headed for Nanyang, where they served as amah, doing the housework and caring for the young.

“I was reading about those women and started thinking about what you would do in China at that time if you didn’t fit the mould, so to speak. At the same time, I was thinking about the goldfields of Australia and the Chinese trek for gold,” she says. The two came together in her second book, an adventure story, released last year.

Immigration records show that between 1856 and 1857, 16,500 Chinese miners arrived in Robe, South Australia, and walked 200 miles to the central Victorian goldfields of Ballarat and Bendigo, among others. Only one of the arrivals was a woman. Presumably, she was someone’s daughter or wife, but there is no record of that.

“I asked myself, ‘What if there was another woman hiding among all those men, dressed as a man? And I started imagining.”

As a result, feisty Little Cat, disguised as The Boy with Blue Trousers, joins governess Violet Hartley, newly arrived by boat from England, and the throng heading for New Gold Mountain. Both women have nothing in common except that one is running for her life and the other, from social death. They do not like each other but soon realise they need each other to find courage and compassion.

There is lots of sadness and vengeance in Jones’ novels, though she says she believes in forgiveness more than revenge. “I think the whole point of this is the characters have to learn to forgive. That’s my lesson in life too — to let things go, though I don’t always succeed and get a bit annoyed sometimes.

“Literature is about bad things and sad things happening and having to find redemption in some way. If there’s any message in my writing, it’s that there always is a reason, right or wrong, people do things. What is it in their family or cultural background or the experiences they’ve had that leads them to behave the way they do? If we can understand that, perhaps it would be a kinder world.”

Building a story

Setting, dialogue, characters and themes are all part of a mixture that bubbles in Jones’ mind when she starts a book. “Often, the story is integral to a particular time and place, so it cannot be separated from the setting. Then the characterisations begin to build.”

Not an early riser, she starts her morning with yoga, followed by breakfast and a walk before settling down to read, research or write.

“As writers, we’re always looking for distractions so we don’t have to write. It’s always hard putting those first words on paper every morning. My routine is to never finish for the day at the end of the chapter. I try to make sure I’m halfway into something and know where I’m going when I come to it the next day.

“I don’t think about writer’s block; I sometimes just find the going harder and have to force myself to put words on paper. It might not be good words, but you can always come back and rewrite. I edit and rewrite a lot as I go.”

Jones has a first draft on a family mystery set in Australia and the UK with a dual timeline — the present day and around the turn of the 20th century. Next, she wants to write a seafaring story set in the South Pacific. And, “if I ever get there”, a detective story set in China in the 18th or early 19th century.

“Not many people know this but there was a period in Southern China when some women had two husbands, not legally — we know this because they were taken to court for that — but because of poverty. They needed two incomes to support the family.

“It wasn’t very common but I read a paper on that by someone who was researching the judicial records. My what-if question is: What if one of the husbands is murdered? Who did it?

“During that period in China, if you ended up in front of the local magistrate, it was basically assumed that you were guilty. What if another magistrate is intrigued by the whole story and decides to investigate it for himself? And, in the process, what if he falls under the spell of the wife?”

The whodunit could take off in any direction. Readers just have to wait to find out where Jones’ open-ended question leads her.

This article first appeared on March 2, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.