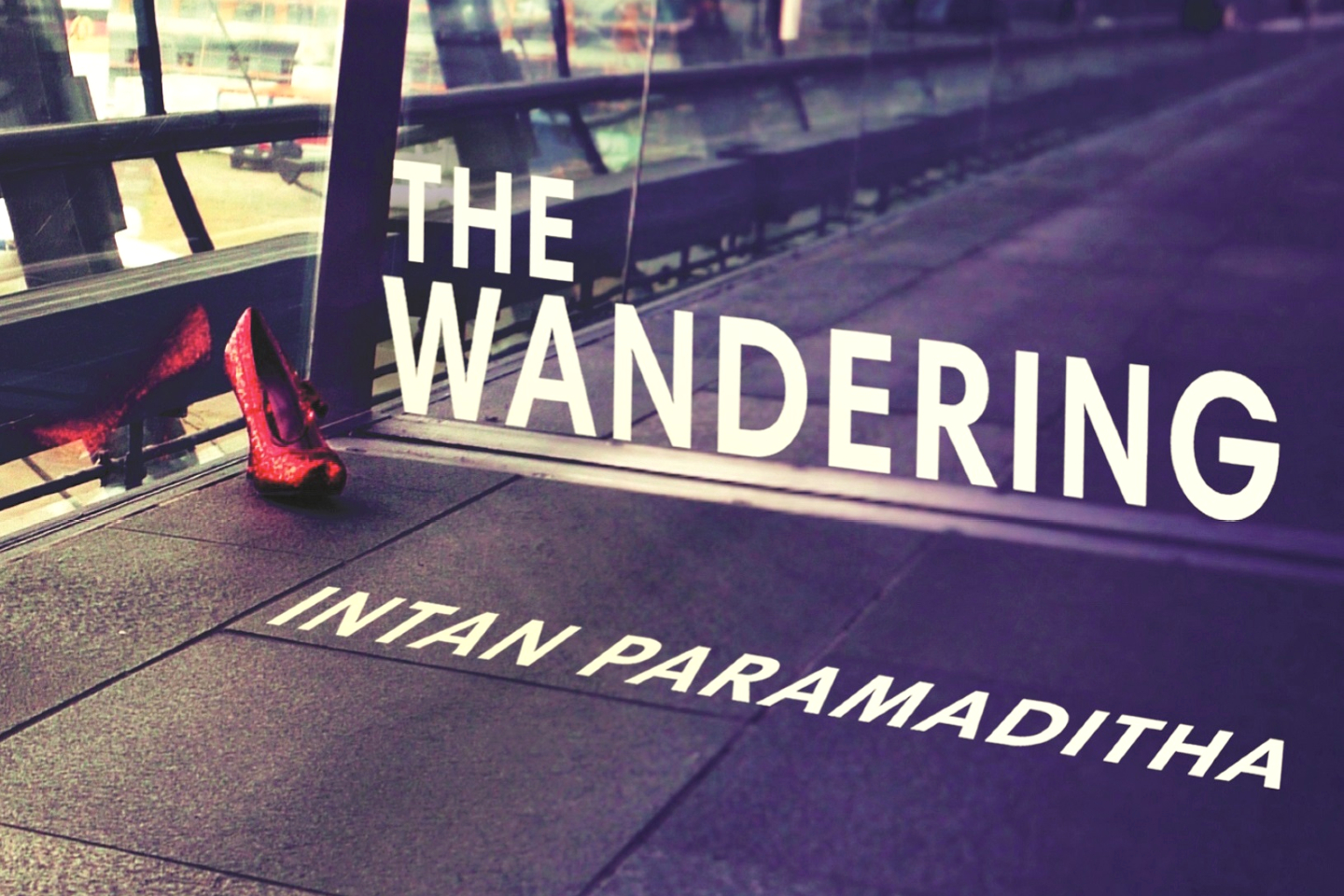

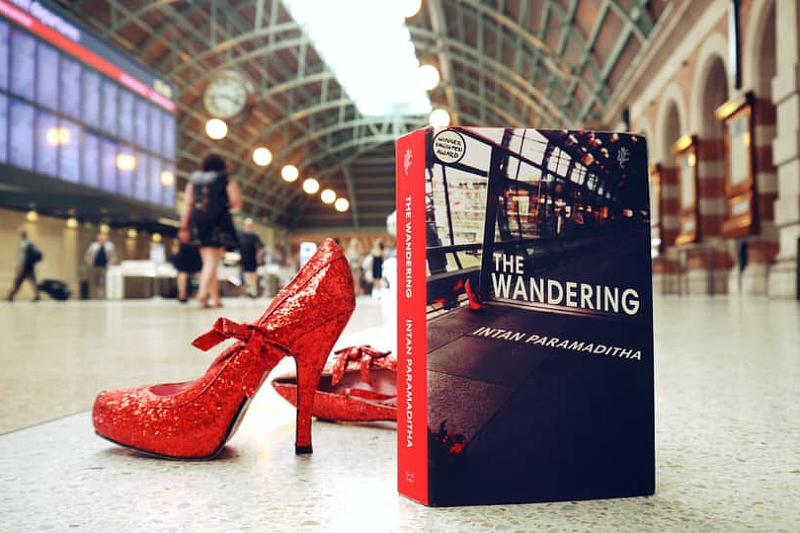

The Wandering was translated by Stephen J Epstein from the Indonesian edition titled Gentayangan: Pilih Sendiri Petualangan Sepatu Merahmu (All Photos: Intan Paramaditha)

In The Wandering, a young woman bored with teaching English in Jakarta, a city “full of thwarted suicidal urges”, makes a pact with her Demon Lover. He gives her a pair of red shoes that will take her wherever she wants to go — but the present comes with a curse.

Intan Paramaditha’s debut novel was translated by Stephen J Epstein from the Indonesian edition titled Gentayangan: Pilih Sendiri Petualangan Sepatu Merahmu (2017) after it won two grants from international writers’ association PEN. It centres on borderlands and global nomadism, desire, mobility and displacement, the politics and privileges of travel, and how freedom and limitations tip the choices we make.

Its protagonist remembers her mother’s warning — “bad girls go wandering” — but like the disobedient woman who gives in to an addiction, she grabs her options on a wing and a prayer as her red shoes click-clack across land and sea, from Indonesia to the US and Mexico, through dirt-filled streets, hotels, graveyards, nightspots, markets and mosques. En route, fellow travellers share gory, sorry stories.

indonesian_writer_intan_paramaditha_1.jpg

Intan did her PhD in cinema studies at New York University and now teaches media and film studies at Macquarie University, Sydney. She has two short story collections, Sihir Perempuan (2005) and Kumpulan Budak Setan (2010, with Eka Kurniawan and Ugoran Prasad), from which the stories in her first collection in English, Apple and Knife (Harvill Secker, 2018), are drawn.

Her fiction, which won the Kompas Best Short Story Award and Tempo Best Literary Fiction of the Year in her homeland, does not fight shy of gender, gore and sexuality as she pushes boundaries both real and imagined, particularly those rooted in culture and politics.

Options talks to the author in an email interview.

Are you a disobedient woman?

Yes, of course. In order to make changes, you need to ask questions and disobey. Disobedience is needed to move things forward.

What shaped your feminist perspective? Was it the result of things that happened in your country or increasing awareness after you moved to the West?

I became interested in the feminist perspective when I was an undergraduate at the University of Indonesia. At that time, my questions started with my family: Why didn’t my mother behave like a ‘good’ mother? I was studying feminism and realised that instead of asking why someone wasn’t a ‘good’ woman, I should have asked what made someone a ‘bad’ woman and what constructed good or bad. Starting with my mother, I became interested in disobedient women — women who resist the structures that confine them — and the stories behind them.

Did your mother ever tell you that bad girls go wandering?

Not exactly. My mother didn’t have the opportunity to travel or to wander the way she pleased because she had no economic privileges to do so. But she taught me how to fight.

When I was a child, I was very shy and quiet and I had problems with bossy kids. Some of them were real bullies. My mother told me I should always stand up for myself and that’s what I will always remember from her.

She wasn’t a writer, but she taught me how to read and write. She was the model of disobedient women in my stories. Her traces are everywhere in my writing.

the_wandering_book.jpg

The protagonist in The Wandering talks about being displaced. Do you feel that way now that you live abroad?

Yes, but displacement is more complex than something that happened in the past, for instance, something you felt when you first went abroad and now you don’t feel anymore. For many people living in between worlds, the sense of displacement is ongoing. It might come and go, not something you get over with. You can feel displaced in your home country, too. You think your home will remain the same, but each time you go back, there are always new things you don’t recognise.

Why horror? Does it get what you want to say across better?

I was a big fan of horror literature, Shelley, Poe and gothic literature in general, and I also watched a lot of horror films. I guess I was interested in the unknown and, well, I grew up with horror. People tell ghost stories around me. What can I say — I’m Indonesian.

When I was writing my BA thesis on Mary Shelley, I became interested in horror stories written by women. I started digging more and found works by Margaret Atwood and Angela Carter. Horror makes you question your assumptions of reality and, as such, I believe it’s a great vehicle to talk about feminist ideas. Just like horror, feminism urges you to interrogate. You need to recognise your patriarchal reality in order to get out.

Has the #MeToo movement made readers more aware of what writers like you are doing by putting the spotlight on feminist concerns?

To some extent, #MeToo has made feminist novels and stories more visible. However, women writers from different parts of the world have voiced feminist ideas before the movement. I think it’s important to make people aware that women — especially in the non-Western world — have been fighting a long time. If we are only heard recently, it just shows how sad our global conditions are.

Are the various narratives and open endings in your novel reflective of the possibilities we miss out on in life?

We are always haunted by the paths we didn’t take. The novel allows a fantasy of looking at various possible paths you could have taken. Some endings are fantastic, such as being on a train that will not stop. But some others are events that happen in real life: marrying a wealthy white guy much older than you to get a green card, living with an undocumented migrant, and raising a stepdaughter you love. People experience these things and make these decisions.

Mobility and choice are key threads in The Wandering: The characters decide where they want to go, and readers pick which pages to turn to. What made you write the novel this way?

I was, of course, a reader of the Choose Your Own Adventure series in the 1980s. After I published my first book, in my mid-20s, I wanted to write a novel in which readers select their own narrative paths. However, conceptually, it wasn’t strong enough. I couldn’t find a strong reason to use the structure, so I abandoned the idea.

In 2008, I wanted to write a novel about our globalised world and the consequences of [being in] various categories, such as tourists, migrants, expatriates or refugees. What moves people? What stops people from moving? It was going to be a novel about travel and where you want to go, but of course the freedom to choose is an illusion. At that time, I felt I could really connect the forking-path narrative with what I wanted to say.

People tell me they have enjoyed The Wandering, but it’s a rather demanding book. It’s not something you can finish in one sitting. It’s easy to get lost in as well. Some readers have used sticky notes to help them mark their paths.

The book has observations about life in Indonesia, many of them negative. Has leaving home made you see things more clearly and given you a stronger voice?

Being away tends to make someone see their home with a critical distance, although I’ve also met many diasporic Indonesians who romanticise everything about Indonesia. I think if you are concerned about your country, you should be critical about it — and about your own attachment to it.

Your collection Apple and Knife has well-known fairy tales that you rewrote. What are some of them and what happens at the end?

Some of these well-known fairy tales include Western ones such as Cinderella, or stories from the Quran, such as that of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife. I grew up with Islamic stories. I also worked with Indonesian legends. I reframed these stories with a feminist perspective. Apple and Knife is also about fantasies of revenge. When justice does not work, violated women solve problems with their own hands. And, of course, in revenge stories, things don’t end happily.

apple_and_knife11.jpg

Is there a message in your books? Do Western readers read them differently from those back home?

I guess they are questions, not messages. For instance, in The Wandering, I ask: Why do people travel and what makes it possible? Who can cross borders? Who encounters boundaries?

I think there are some similar ideas that Indonesian and non-Indonesian readers take from the book, including feminism, power, travel and privilege. But some cultural contexts remain specifically Indonesian, and I think that’s okay because there are always things lost in translation.

Are there any particular authors who have influenced you, and why?

I was influenced by women writers who wrote dark pieces with a feminist perspective, such as Shelley, Atwood, Anne Sexton and Indonesian poet Toeti Heraty.

Does teaching help your writing or does it eat into time that could be spent creating fiction?

My academic work helps shape the way I analyse issues and think about the world. It provides an important framework for my fiction. But, of course, being an academic means you need to teach, do university admin work and do research. That means you do not have all the time in the world to write fiction.

Writing every day for two hours is always an aspiration. I write fiction at the weekend, if I have the time.

Do you begin with the character or story in mind, and how would you describe your style?

I usually start with the characters and plot — I will not start writing without having clear ideas of these two. My style of writing serves the story, which comes first. Then I will think about how it should be written.

What are you working on now? Will you continue to explore sexuality in a gory way?

I am working on the idea of remorse, but I can’t spill too much because it’s still at an early stage. It may not focus so much on sexuality, but it will still be a feminist story.

This article first appeared on Apr 13, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.