Clockwise from top left: Dr Kannan Pasamanickam, Dr Ding Chek Lang, Dr Dewi Ramasamy, Dr Zainal Hamid, Dr Madhav Kudva, Prof Peh Suat Cheng, Dr Yogeswery Sithamparanathan and Dr Abed Onn (Photo: SooPhye)

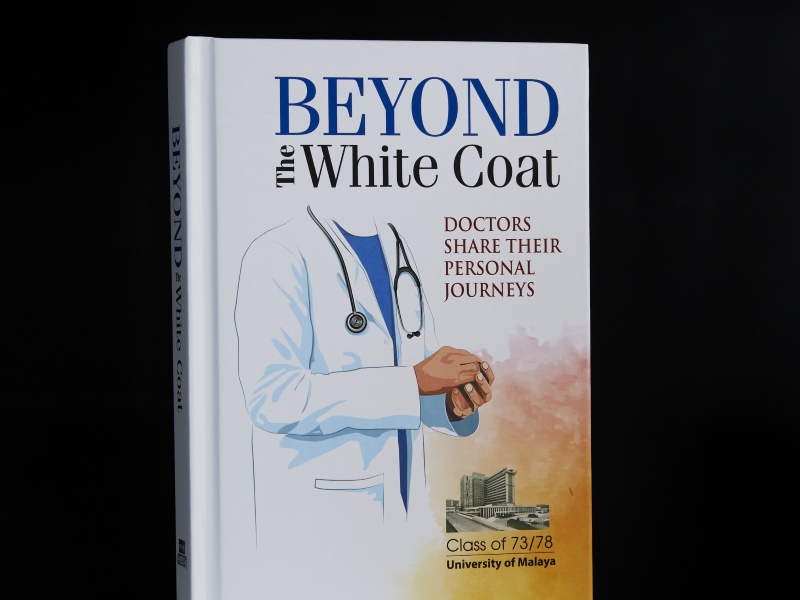

Those who have read When Breath Becomes Air, the beautiful and evocative autobiography by the late neurosurgeon Paul Kalanithi that documents his battle against stage IV metastatic lung cancer, can rest assured they won’t be ugly-crying while reaching for the Kleenex in Beyond The White Coat.

Despite the stature regular folk bestow unto medical practitioners because of their ability to save lives — backed by a powerfully eloquent quote from the great Roman orator Cicero, who said “in nothing do men nearly approach the gods, than in giving health to men” — doctors are human too.

It is upon this premise that 21 doctors from the University of Malaya’s Class of 73/78 decided to compile their stories in a witty anthology that is part memoir, part musings. Given that the initiative is driven by the 10th batch of students led and taught by the medical school’s legendary founding dean Prof T J Danaraj, the good doctors are determined that those in need are always helped, even as scalpels and stethoscopes are temporarily traded for pen and keyboard. As such, all proceeds from the sales of Beyond The White Coat will benefit the patient welfare fund of Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) Hospital.

as1a4166a.jpg

Doctors are humans

“It dawned on a group of us, sometime in mid-2022, that we had all been blessed with interesting lives,” said Dr Zainal Hamid, graduate of the class of 1978 who went on to become a pioneer cardiologist with Institut Jantung Negara (IJN), Malaysia’s first cardiac-dedicated hospital. Together with Dr Kannan Pasamanickam and Dr Madhav Kudva, the trio served as the de facto editorial team and key drivers of the project. “Emails were sent to classmates. We wanted those who agreed to participate to write about their experiences in medical school, postgraduate training, as doctors … especially their interactions with unforgettable patients!”

It took a bit of cajoling as many of them were modest, thinking their lives were far from extraordinary. “Our collective backgrounds are equally varied, with some the children of pioneer doctors, and others taxi drivers, teachers and so on. All in, 21 classmates contributed, some of whom initially tried very hard to avoid medical school — their reasons certainly make for interesting reading.

“And we hope readers will acknowledge that what is presented are outstanding examples of discipline, grit and human endeavour while future generations of doctors can hopefully learn something from our successes as well as failures. There was also an urgency to complete the book as we were increasingly reminded that life is finite, with the passing of some classmates due to various illnesses.”

The tales, all neatly arranged in individually written chapters, range from the humorous to the poignant and painfully raw. Eminent gastroenterologist Madhav’s story documents the push factor that made a small-town Bidor boy give up his dream (and scholarship from a renowned US university all secured) of becoming a space engineer.

“All boys want to be rocket scientists, no? But I was once so sick that I needed admission to a private hospital in Ipoh managed by Christian missionaries. The compassion and care shown by the physician and nurses during my stay left a deep impression and made me decide that medicine, rather than space engineering, was my calling.”

university_hospital.jpg

Cardiologist Kannan’s case serves as a reminder that while doctors are healers, they are not exempt from illness. This fact was driven home when he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a potentially life-threatening blood disease, in late 2017. “It was my turn to view medicine from the other side of the bed,” he says wryly. After undergoing a successful bone marrow transplant in 2018, a procedure that would give Kannan the best chance to effect the longest duration of remission from myeloma, the energetic doc took just three months to rest and recuperate before delving back into things.

“I continue to practise because it is therapeutic,” he grins. “I have, however, stopped doing night calls since 2022 and reduced my clinic hours. But interventional work still thrills me, so I continue to perform coronary angiograms and angioplasties.”

For obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Neoh Hock Sun, a serious motorcycle accident in his first year of university nearly put paid to his dreams of becoming a doctor. “My spleen and left kidney had to be removed,” he writes in Chapter Four. “After regaining consciousness post-surgery, I remember begging the staff to discharge me as I had an anatomy exam the next day and could not afford to fail.”

Further complications ensued, to the point of necessitating a second operation, enforced bedrest for a month and then physiotherapy, because muscular dystrophy had set in as a result of disuse. “When I returned for lectures, I was told I wasn’t qualified to sit for the final year-end exams as I had missed too many lectures and so had to attend the referred class and take the supplementary exam. I passed and, due to my experience, can now empathise and sympathise with my patients better. I can reassure them on a more personal level because I have gone through the same trials and tribulations and come out successful at the end.”

classgettogether.jpg

Serving one’s fellow man

One of the more interesting aspects of Beyond The White Coat is finding out the myriad motivations for choosing medicine as a career. This ranges from personal experience after seeing illness and injury strike the family — as was the case for pioneer cardiologist Dr Dewi Ramasamy, who resolved to become a doctor after losing her six-year-old sister in a tragic car accident — to the classic Asian reason: parental persistence. It is also enlightening to learn that medicine is one of the most accommodating careers, suitable for a staggering variety of personality types. However, grit — bucketloads of it — is needed.

Yes, brains account for a great deal but all doctors require the fortitude and endless reserves of mental and emotional strength in order to endure a barrage of examinations, sleepless days and nights (particularly during the gruelling houseman years) and the determination to never give up on patients who depend on their knowledge and care. Dr Ding Chek Lang, Malaysia’s first British-certified urologist, affirms that: “As Prof Danaraj told us, ‘medicine is a lifelong course’.” Dr Yogeswery Sithamparanathan nods in agreement, saying, “Knowing the technique of healing and diagnosing is not enough. You need passion to pull through each day and every doctor [has] to be fully committed to their patients.”

The former head of Klang General Hospital’s paediatrics department, a position she held for 27 years, Yogeswery was instrumental in modernising the unit, especially its neonatal intensive care facilities. “I was in the UK in 1982 to continue my paediatric training at hospitals like Great Ormond Street and Queen Elizabeth, London,” she says. “Exams were very tough in those days and I pledged to dedicate my career to caring for needy children once I completed them. However, a year after my return, I was devastated to be posted to Klang Hospital, having heard several adverse remarks about the place.”

yogeswery.jpg

Overcoming her initial apprehension at being sent to an old, still semi-wooden structure, Yogeswery evolved from being its youngest head of department in 1984 to retiring in 2011 as its longest-serving. “Upon reflection, I have so many fond memories of my service, especially to the children of Selangor. I used to cover district hospitals as far away as Tanjong Karang, Kajang and Banting, as Klang GH was the only general hospital in the state until the late 1990s.

“As of 2016, I assumed an academic position in a private medical school, becoming fully involved with training students in paediatrics. It was a somewhat difficult transition to withdraw from clinical service but I am now thoroughly enjoying myself, being able to interact with young minds and playing a significant role in moulding them to produce young doctors of calibre who will uplift our healthcare system.”

Serving one’s fellow man, meanwhile, seems to run in Zainal’s genes. The grandson of Dr Abdul Latiff Abdul Razak, the first Malay doctor in what was then known as Malaya, he acknowledges how medical school “stretches one’s resilience to its limits” and that his first posting after internship was to the incredibly busy Emergency Department of the General Hospital Kuala Lumpur. “Probably the best place to gain experience, though,” he admits.

Zainal, now semi-retired, has a barrage of tales to tell, including being the first to perform primary angioplasty in a patient with myocardial infarction (a heart attack, to the layman) as well as do transradial angiograms and angioplasty, where angiograms are performed through the radial artery in the hand versus the conventional femoral route through the leg. The jolly 72-year-old sums up his journey by saying, “I am fortunate to have lived through an era of extremely rapid development in cardiology, which I doubt we will see a repeat of in a long time. It has been a full, satisfying and adventurous life, and I managed to mend a few ‘broken hearts’ along the way,” he wisecracks.

Not always a spoonful of sugar

Despite the nobility of the profession, injustice does rear its ugly head from time to time. For pathologist Prof Peh Suat Cheng, hers was a particularly bitter pill to swallow. Once named among the top 2% of research scientists in the world, she had her 35-year career in science and pathology at the University of Malaya abruptly cut short after the faculty denied her “no pay leave” request to care for her terminally ill husband. “I resigned without a second thought,” she recalls.

Today, as Sunway University’s professor of pathology and dean of the School of Healthcare and Medical Sciences, the soft-spoken 71-year-old has clearly moved on from that episode. “In hindsight, the university declining my applications was a blessing in disguise as it provided me the opportunity to have a welcome change in life. There was no reason for me to be angry or bitter anymore,” she says.

The indefatigable Peh shows no signs of slowing down and still displays a great zest for life. “I went on a safari in Tanzania when I turned 60 and, last year, my birthday gift to myself was an expedition to Antarctica!” What currently occupies her time is her dream of opening a day-care centre for seniors, which was sidetracked by Covid-19.

as1a4242a.jpg

Dr Abed Onn, who once contrived to achieve career goals of a non-medical nature, humorously dedicates part of his story to the art of skiving. “I remember very clearly the many times factory workers would come see me, complaining of symptoms of gastroenteritis and asking for a day off,” the occupational health doctor grins. “Invariably, this would peak on Fridays, Mondays, or the day before or after a public holiday. I was initially sympathetic and signed the medical leave slip. However, after noticing the ‘trend’ and being informed by the nurse at the factory clinic that I was a ‘soft touch’, I had to do something.”

Wise to the ploys of errant employees, Abed soon began asking for stool samples. “But guess what? An enterprising staff began mixing his own stools with water and selling them as ‘diarrhoea samples’ to his colleagues,” he says with mock exasperation. “Management then conducted an investigation on this enterprise and fired the mastermind.” But the trickery did not abate and Abed was forced to include rectal examinations as part of patient evaluations. “Although this cut down the number of such cases at the in-house clinic, workers began frequenting clinics outside of the factory to continue their hunt for MCs.”

He adds how, once while making the customary rounds in the ward first thing in the morning and last thing at night, a patient queried him about a houseman’s remuneration. “I told him and his response was, ‘Wah, my driver is earning more than you ah!’ But wait, it gets worse. I remember how the recruiting agents from a credit card company had cleverly come by when we all received our final exam results, eager to get a host of new clients. We had to enclose a copy of our payslip as proof of financial stability. Guess what? The agent called back to sadly inform us that no one was eligible to be issued a card as we weren’t earning enough!”

But back to that quote by Cicero. Doctors, blessed with the knowledge to heal and cure, do seem touched by the divine. In a world obsessed with science, technology and artificial intelligence, now is as good a time as any to remember that despite all the advancements and how robotics increasingly muscle into more aspects of our lives, nothing is as reassuring as the physical touch, comfort and care of a dedicated medical practitioner.

“I remember the wisdom of Prof Danaraj who cautioned us a long time ago, regarding pharmaceuticals in particular,” Ding adds on a parting note. “He said the day you rely on information from [such] companies with which to use medications is the day you ought to retire as a doctor. Indeed, we need to be ever so cautious when grappling with both pharmaceuticals and technology — for our patients’ sake.”

But Beyond The White Coat, with its collective stories of struggles, success and sacrifice, also reminds us that doctors are — at the very heart of it — mere men and women. Composed of flesh, bone and blood, their key distinction lies in a sworn duty to uphold the Hippocratic Oath. They are human, just like any of us. Maybe blessed with better brains. Oh, and definitely bigger hearts. Of that, there is no doubt.

'Beyond The White Coat' launches on Sept 8 at University of Malaya’s Faculty of Medicine with a special foreword by Datuk Seri Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, ophthalmologist, former deputy prime minister and wife of Malaysia’s sitting premier. See here to purchase copies. All proceeds will benefit UTAR Hospital’s patient welfare fund.

This article first appeared on Sept 9, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.