Seldon: A good school will always find out what he or she is best at, so they will not be pressed into being something else (Photo: SooPhye)

Schooling should be a magical experience for young people. Yet all too often, the joy is squeezed out of school, leaving students afraid of failing, making mistakes, disappointing their teachers and letting down their parents.

What should be joyful has become for far too many an unhappy experience, which accounts for more and more parents who want their children to be homeschooled, and increasing numbers of the young refusing to attend classes, especially post-pandemic.

Polls across the world show students are becoming less happy at school, “which is terribly sad and completely unnecessary”, says British educator, author, political commentator and contemporary historian Sir Anthony Seldon. He should know.

Seldon, 70, is prominent for introducing lessons on happiness and well-being in the school curriculum. He advocates character education, which involves learning about goodness, communication, problem-solving, relating with others and coping skills.

“I mean, bad stuff will happen and things are going to go wrong. Students will not always get into the university of their choice or the jobs they want. They will have girlfriends or boyfriends who chuck them and they will be let down. Grandparents will die and we, as parents, are helpless to stop those sad things from happening.

“But what we can do is build their resilience and ability to cope with adversity so they can have smiles on their faces.”

The head of Epsom College UK was in Malaysia recently to meet with teachers, parents and students of its sister institution in Bandar Enstek, Negeri Sembilan. Epsom, an English independent day and boarding school in Surrey, southwest of London, was founded in 1855 by Dr John Propert to assist elderly doctors, their widows and orphans.

epsom_college_uk_2.jpg

In March this year, Seldon was asked to helm Epsom following the tragic death of head teacher Emma Pattison, who was found dead alongside her seven-year-old daughter, Lettie, in the early hours of Feb 5. The pair were believed to have been shot at their home on the school grounds by Emma’s husband, George Pattison, before he turned the gun on himself. Emma, the first female to lead the school, had assumed her position just five months earlier.

Seldon’s interim appointment is until September 2024, after which Mark Lascelles will take over. How did he lift the spirits of students and teachers after stepping in at a most difficult time?

“By using optimism and not dwelling on what had gone wrong; by acknowledging that things had gone wrong, but not be engulfed in it,” Seldon says.

Which loops back to his deep and long-held belief that school should be a happy place where students discover things about themselves and what they love about life, and learn to live well with the skills they have.

The word “education” means to lead out, that is, schools must locate the gifts each young person has inside and draw them out, Seldon believes.

“A good school will always find out what he or she is best at, so they will not be pressed into being something else. Rather than focusing on what children cannot do, we should be finding out what they can. All young people have gifts, intelligence and aptitudes that schools should be actively nurturing. Because if these are not discovered, they will be unsupported and their unique skills will be left dormant.”

Human beings have many different kinds of intelligence and accepting that everyone — even siblings — is different is the first step towards tapping a person’s strength and not focusing on his weakness.

“My brother couldn’t get on at school, didn’t pass any exams at all. But he went into business and really took off,” Seldon shares. “I loved books. I loved thinking, being part of the class, learning material, and trying to understand what was happening and to connect the dots to make patterns.

“Every kid has it in him to do something good and it’s up to the teacher to draw that out. Every child wants to please his parents, his teachers, his school. Children want to be well thought of, and you need to go with the grain of that.

“Children are going to make mistakes, they’re going to be naughty, they’ll get into trouble. It’s worrying if they don’t ever get into trouble. I’ve done things that were wrong, and the teacher would build bridges. And I had some great moments when I was a teacher.”

A theme that comes through from his students daily is coping with stress and expectations, and pressure from many different directions, he observes. How do we help them navigate through these and still flourish?

One answer is positive psychology, which highlights what it means to be an accomplished and happy person, instead of, say, obsessing about fear, eating disorders, alcoholism, abuse or misery, Seldon suggests.

Imagine there is a river with a sharp waterfall. What happens is many children and adults are carried along by the current, and they fall off the river and something terrible happens to them.

“Positive psychology is about working at the top of the waterfall to give children, and parents, the skills of living, instead of rushing in and trying to put them back together again after they fall and hit the bottom,” he adds.

In 2021, Seldon initiated the Times Education Commission to “examine Britain’s whole education system and consider its future in light of the Covid-19 crisis, declining social mobility, new technology and the changing nature of work”. This landmark event in education in the country produced one of the most influential reports of its kind.

First and foremost, the initiative found that education is badly out of touch with what employers require today. It is based too much on the passing of tests and examinations, and a passive form of cognitive intelligence that bears little relationship to the requirements of the workplace or modern society.

“In its place, we advocate active rather than passive learning, and far more focus on skills and character that young people will need when they are at university and at work. What is true for Britain applies equally to Malaysia, as it does to Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

“In all these countries, we have allowed education to be narrowed down to the mere passing of exams. Exams are certainly important, but we have let them become all-important, and we have to change direction.”

Too often, the commission also found, many young people who achieve brilliant results at school do not succeed at work, and are troubled by mental health issues. At the other end of the scale, many of the most successful entrepreneurs in all fields, and the happiest people leading successful lives, did not succeed academically at school.

“You can have people who are intellectually brilliant, but they can’t relate to customers or clients and that’s no good. You know, it would be much better if somebody was less intellectually brilliant, but more emotionally good.

“It makes no sense at all to educate young people without helping them learn to manage their own minds, emotions and bodies.

“Well-being and character education need to be at the very heart of schools, not on the margins. Schools need to be encouraged to take well-being as seriously as exams. Young people need to learn to be positive, and look for the good and the healthy in everything they do.”

epsom_college_malaysia.jpg

Looking at the findings, Seldon says, “We need to change [our] approach and use the new technologies that are at our elbows, including artificial intelligence (AI), to reimagine education.”

Some of the tasks handled by educators will be taken over by AI, like marking and lesson preparation, leaving more time for teachers to interact with students. But the job itself — “it’s pastoral” — will not be, he thinks, because “we’re teaching children, not just subjects”.

Education is changing and it is not an either-or situation, he emphasises.

“It will be changing in Malaysia, Singapore, India, in the Gulf and Turkey, Greece and all the way back to the UK and US. It’s just going to. It’s just changing because the technology is changing, the needs of society are changing, the needs of the economy are changing. The medical understanding of human beings is changing. So, we will change and Malaysia could be at the heart of all that.”

Seldon, whose first academic appointment was in 1983, says the greatest skill of teachers is to let the students blossom and achieve understandings that had previously escaped them. “Too many teachers seek the limelight themselves, talk far too much during lessons and infantilise their students.

“The best teachers are always the most humble, and they are full of love, not their own egos. My best moments as a teacher were always when children had the ‘aha’ moment — when they suddenly realised something, and felt enormous pride in themselves.”

As for himself, the aha moments were aroused by his history or science teachers who developed his curiosity and helped him to ask questions about the nature of matter, or why wars happen? Or, why peace breaks out and what happens with peace?

“Teachers have enormous ability to affect the lives of young people for decades into the future: No profession is more important. I would like everyone reading this to become a teacher, or encourage their children to become one!”

Asked what led him into the profession, Seldon credits his late wife Joanna Pappworth, who died of endocrine cancer in 2016. They met while at Oxford University.

“My first wife became a teacher and I thought I didn’t want to be an academic because it was dry and not very interesting. As an academic, you don’t really have very close relations with your students — they come and go quickly. But being with children, you’re much more important.

“I love school. They’re amazing places and you’re learning. Every day, you’re learning so much and you’re with imaginative, good people. I think it was really Joanna’s influence. She was the person who led me towards this, and I quickly found I loved it.

“I never thought I’d be a teacher; I always wanted to be a writer.”

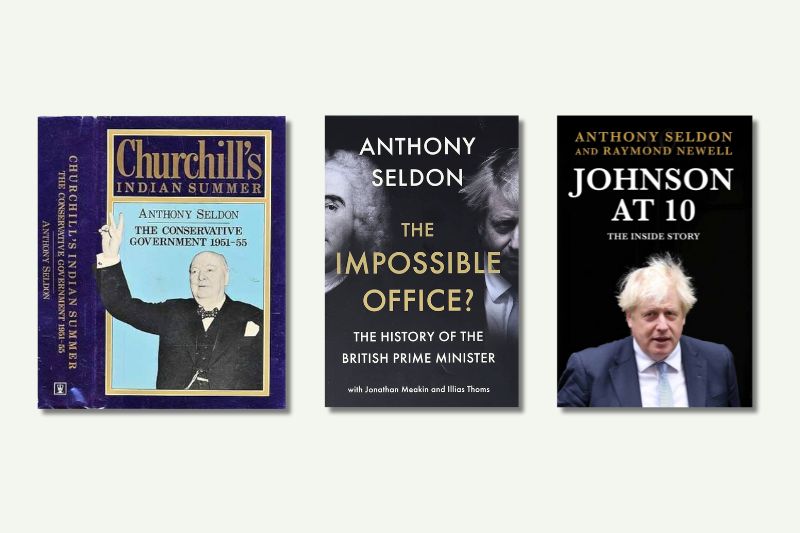

sir_anthony_seldon_books.jpg

Writing may be secondary to teaching for Seldon, but he has carved his reputation as “the historian of Number 10 Downing Street” for his biographies of six consecutive British prime ministers: John Major, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron, Theresa May and Boris Johnson.

Over the last four decades, he has written and edited more than 40 books on contemporary history, with prizes to boot. Churchill’s Indian Summer, published in 1981, won him a Best First Work Prize.

In 2021, he wrote The Impossible Office? The History of the British Prime Minister, which explores the lives and careers, loves and scandals, successes and failures of 55 of the country’s great leaders, from Robert Walpole to William Pitt the Younger, Clement Attlee and Margaret Thatcher. Besides discussing who has been most effective and why, he also weighs the increasing power of the PM versus the steadily falling influence of the monarchy.

In Johnson at 10, released in April this year, he says this of Boris: “At heart, he is extraordinarily empty … Johnson could have been the prime minister he craved to be, but he wasn’t, because of his utter inability to learn.”

Drawing from his books on the seven premiers, what has he learnt most?

“I think how sad they are with their lives. You would expect them to be very happy having risen to the top but they are tortured souls.

“Some people are happy in politics, but most are dissatisfied. Every prime minister finishes in tears; it never finishes well. It won’t for Rishi Sunak, our current prime minister. It won’t for [British opposition leader] Keir Starmer, who will be the next PM.

“They always end badly, almost all. Why? Because they don’t do what I say: They didn’t pause and reflect on what they were doing. They were just swept up by their egos and the adrenaline and the rush. They didn’t know what they were going in for, or it was too big a thing for them to fathom.

“Yeah, they’re aware of the unimaginable honour of leading their country. But when they’re in there, old habits take over. You know, for a moment, they’re surrounded by a halo of greatness and they’re humble and wanting to be their very best. But the habits come back very quickly … and they just try doing things as they’ve always done. Very few learn how to do the job of being a prime minister.”

Seldon, a teacher who always encourages students to ask questions, did not mind taking one that is personal: Has his second marriage to Sarah Sayer last year brought him a happiness he never imagined possible?

“I am very lucky to be married to a remarkable woman. And, yes, it’s a different experience where your partner dies.

“I mean, it happens to an increasing number of people and it was the hardest thing I’ve ever faced. I still wonder how I got through it. Other times, I wonder if I’ll ever get really totally through it.

“It’s very lovely to be married again. I don’t think that when somebody you love — whether a child, a much-loved parent, a spouse or a sibling — dies, you ever get over it. But life grows around [their passing] so that your life isn’t so defined by it.”

This article first appeared on Dec 18, 2023 in The Edge Malaysia.