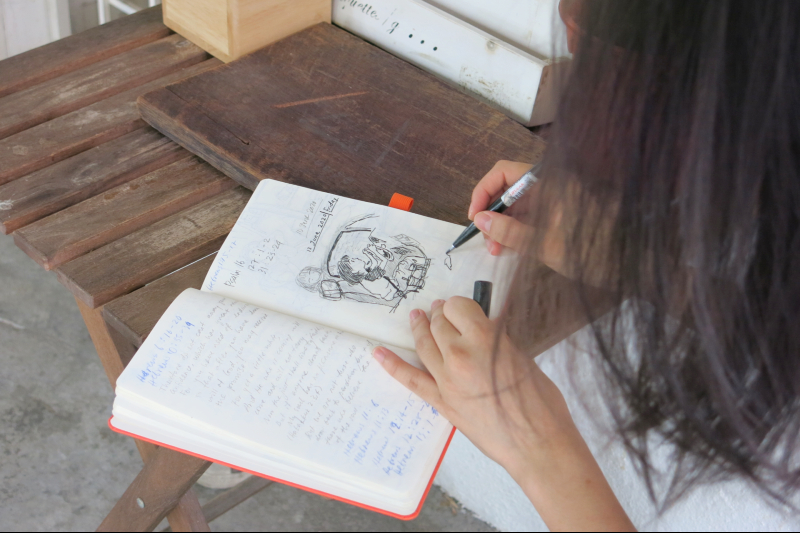

The 21-year-old hails from Batu Pahat, Johor (Photo: Emily Yap/The Edge)

With all the modish cafes Kuala Lumpur has to offer, Erica Eng’s choice of a quaint and cosy heritage-home-turned-coffee-bar speaks volumes about her disposition. Eng is a nostalgic individual, a keen observer always absorbing details to add to her worn sketchbook. She flicks through pages of rough drawings for her webcomic Fried Rice before finding a blank page to capture her field of view in ink.

The artist has been drawing for as long as she can remember. She worshipped writers such as Roald Dahl, E B White and Laura Ingalls Wilder, as well as the illustrators they collaborated with, Quentin Blake and Garth Williams. It was her childhood dream to be an author-illustrator, so when she received news that Fried Rice had been nominated for an Eisner Award, the comics industry’s equivalent of an Oscar, it was a full circle moment.

Set in early 2015, Fried Rice follows budding young artist Min, who visits her cousin Lilly in Kuala Lumpur. Brimming with ambition, both plan to travel overseas for their tertiary education. But while Lilly intends to return after completing her studies, Min is bidding her home good riddance.

img_1551_2.jpg

Their respective situations reflect the conflict faced by many young Malaysians today. A prolonged duration overseas often prompts the inclination — or encouragement from family and friends — to migrate. Fried Rice weighs the pros and cons of doing so in a multi-layered way. The dialogue between the characters reveals contrasting views and its visual presentation is just as suggestive. Is the grass truly greener on the other side?

Min’s story is loosely based on Eng’s own experience after completing secondary school. Growing up in Batu Pahat, Eng felt she had gotten the short end of the stick. Not everyone took art as seriously as she did and that frustration developed into a desire to seek out greener pastures or, at least, a community that understood her. “I remember how bitter and frustrated I was as a teenager wanting to pursue art in a small town,” the 21-year-old says. “But I don’t have such a simple view on that idea anymore. I realised how wrong it was of me to think I couldn’t be an artist in that place because I didn’t find my surroundings artful.”

It took a bit of time for Eng to have a change of perspective, during which she focused on her artistic work. She is now pursuing a bachelor’s degree in animation and visual effects via distance learning from the Academy of Art University in San Francisco.

tumblr_7fa67b5e3e6db0f63109d4d55e7b9d9f_68a696e2_1280_1.jpg

Fried Rice is an ode to the place she proudly calls home and represents a reclamation of the time she lost being discontented. The full story spans about 200 pages but at the time of writing, only 49 pages are available on friedricecomic.com. A new page is uploaded every Sunday at 8am until the story ends. “The script is done but I tend to tweak some things even when I draw the final page,” says Eng. “It’s usually based on how the panels go.”

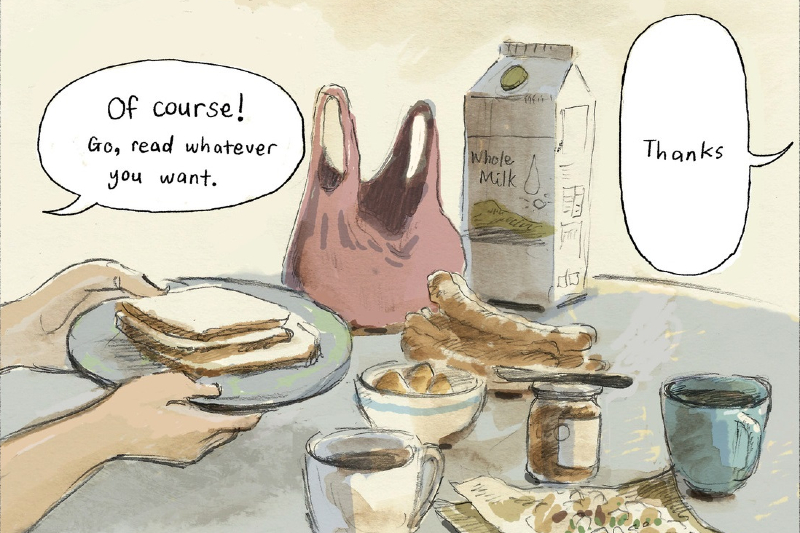

Every page is hand-drawn on paper with pencils and then painted with ink wash. After the drawings are scanned, colours and lettering are added digitally in Photoshop.

Eng says the characters in the webcomic were designed to feel almost ordinary. They are an amalgamation of real people she knew and fictional characters from existing works. “I didn’t try to reach too far out of my understanding when creating these characters because, just like in real life, exerting too much control over people ends up flattening them,” she explains. When asked how she developed her style, she simply says “it felt easy”.

“When I first started out drawing, it usually became very laboured and overthought. It took me a lot of time to get to a place where I was comfortable with the story and knew it well enough so the way I expressed it visually became natural. When it doesn’t feel or look forced, that’s when I know it’s good enough.”

Fried Rice is no action comic. It does not have superheroes or a seesawing story arc. What makes Eng’s work so arresting, especially to Malaysian readers, is how accurately she portrays the character and mood of a scene. Her drawings evoke a sense of familiarity, whether it is eating a packet of nasi lemak for breakfast or attaching a stamp to your mail at the nearby post office. It draws on mundane life and depicts activities you would normally do on a languid weekend morning or conversations you would have with your best friend. These simple scenes make you wonder if they were extracted from your own memory.

tumblr_px4ymh9ofa1yuzue7o1_1280_1_1.jpg

“Having Malaysia as the backdrop was very important because the setting so greatly influenced the experience I was documenting,” says Eng. “I didn’t want to fictionalise the setting much, if at all. I use Google Maps a lot to reference the streets and buildings.”

Even the title itself is benign. “Fried rice is my comfort food and the term itself has a homey feeling that I love,” she shares.

Eng submitted her entry to the Eisner Awards last year on a whim. After the news broke, she was flabbergasted by the support and love she received. She is the fourth and youngest Malaysian to be nominated in the awards’ 32-year history after Tan Eng Huat — better known as Kutu — for his work with DC Comics; Reimena Yee for her digital-comic-turned-graphic-novel The Carpet Merchant of Konstantiniyya, and Seremban-born, Singapore-based graphic artist Sonny Liew, whose graphic novel The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye won for Best Writer/Artist, Best Publication Design and Best US Edition of International Material (Asia) in 2017.

Because of the Covid-19 outbreak, however, the awards ceremony, which was supposed to be held at Comic-Con in San Diego, has been cancelled. Instead, the announcement will take place online late this month.

Unfortunate timing has also resulted in missed opportunities for Eng. Prior to the Eisner nomination, fellow artists including Yee and Charis Loke, who illustrated a mural for Netflix’s adaptation of Yangsze Choo’s book The Ghost Bride, asked her to join a comics coalition. “I was going to go to their workshop in Penang but the pandemic hit and they had to postpone it,” she says. Although she was unable to attend, Eng was glad she could interact with professional artists who were not her lecturers. The problem about not being part of an art community is slowly being resolved.

Eng shares another similarity with Min. Despite loving to draw, both decided to study animation, which turns out to be more technical than creative. “You have to make a lot of creative decisions in animation but if you don’t have the technical skills to back it up, then it doesn’t work,” explains Eng. “It’s very tedious and very different.”

Nonetheless, she enjoyed the challenge. Being able to train both sides of the mind has its perks. “Drawing has helped me compose my shots and pick more interesting acting choices for my animation work,” she observes. On the other hand, film principles she learnt, such as camera angles, continuity, lighting, colour and composition, were applied to her comic drawings. “It’s nice to cross over,” she adds.

Eng recalls coming across an interview with one of her favourite comic creators, Cyril Pedrosa, a French artist who worked as an animator at Disney (Hunchback of Notre Dame and Hercules). Pedrosa has said that if you are in film, it is usually because you want to work with people; but if you are in comics, it is because you want to work alone. “I can relate [to that],” Eng quips. “I think I have two sides of myself.”

In terms of future work, she is taking it slow. “There’s nothing solid yet. I have ideas but they’re all in the incubation stage. I’m patiently waiting for time to coax them into maturity.”

Readers can follow Min’s story in 'Fried Rice' here.

This article first appeared on July 6, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.