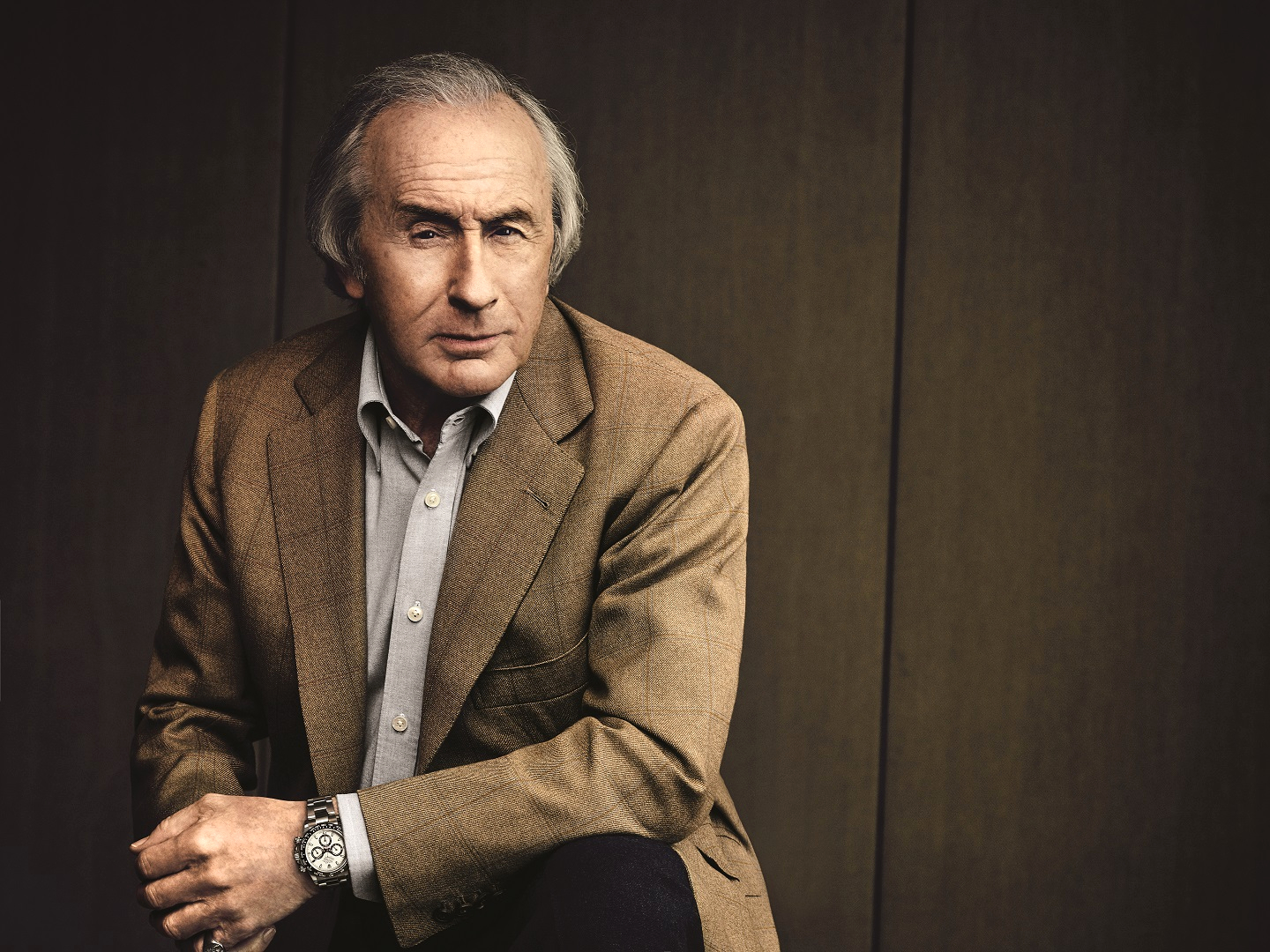

Nicknamed the "Flying Scot", Sir Jackie Stewart won three world championships (Photo: Rolex)

It is not every day you meet someone who enjoyed the company of Queen Elizabeth at his birthday lunch and whose grandchild’s godfather was the late King Hussein of Jordan. Former Formula 1 driver Sir Jackie Stewart works these names into conversation with the same nonchalance as one would dispense Tic Tacs, but what would come across as feigned modesty in others is simply the natural disposition of a high-flyer with both feet planted firmly on the ground.

“I think the greatest driver was [late Argentine F1 racer] Juan Manuel Fangio,” Stewart says at the 2019 Singapore Grand Prix. The 80-year-old Rolex ambassador, famous for his signature tartan trousers and hunting flat cap, occasionally checks the screens in the watchmaker’s suite to keep up with the practice laps on the eve of the Night Race. “I’ve always felt that the smoothest, least spectacular driver is best. When you see drivers busy on the steering wheel, cars going everywhere, they’re over-driving. Fangio drove smoothly and gently, and that made him go faster, use less tyres and fuel. Jim Clark is probably the second best — he was so clean [behind the wheel] too. I would love to think I’m third. Schumacher was very fast, as Senna was, but I think Alain Prost was better than them both. It’s too soon to gauge [Max] Verstappen and [Charles] Leclerc, but they’re both very good.”

Asked to describe his dream race, these same names promptly emerge. “Fangio, Clark, Prost, Schumacher and Senna — I’d like to be racing against the best, because they’re usually the safest. The drivers who are over-enthusiastic usually cause trouble and when you’re driving at very high speeds, you don’t need someone alongside whom you cannot trust,” he says. “I’d like whatever car is the best at the time, but it’s difficult to pick a favourite track. If you haven’t won Monaco, there’s something wrong with your resume. You have to win Monaco. I’d like to turn the clock back because I’d want Princess Grace to be there. It’s also something to win your own Grand Prix (I’m British, so that’s the British Grand Prix), and Nürburgring was important. But I’d like to race here. I’ve never done a night race for F1.”

f1singa19jm_239_2.jpg

Keeping a cool head was an advantage he brought into motorsport, courtesy of a successful if short shooting career. Bullied for being dyslexic in his youth, though the condition did not have a name then and saw him labelled stupid and lazy, he clung to whatever skills he could find. Shooting was the first.

“When you’re dyslexic and you find something you’re good at, you focus much harder on it than people who are clever and are therefore versatile and good at many things,” he says. “I have good hand-eye coordination. My grandfather was a gamekeeper in Scotland, looking after the grouses, pheasants and partridges. He taught me to shoot when I was 14. I went on to shoot for Scotland, and then Great Britain, all around the world. The most important thing I learnt was mind management. I learnt to remove emotions so I wasn’t nervous. If you miss the first target, you never get it back — that’s one loss already, never mind the other errors you might make later. That made a big difference when I became a race driver.”

He bowed out from shooting when he married his wife, Helen, at 23. “Women are very expensive,” he jokes. “I couldn’t afford an amateur sport and a wife, so I became a mechanic in a garage, and then took up racing. Mind management quickly came in handy. I won almost all my races in the first five laps because everyone else was so wound-up or excited. Drivers today don’t have that same nervousness because the sport is different, people aren’t dying the way they used to. I once counted 57 deaths among racing friends and peers. I tell everyone that in the swinging 1960s and 1970s, sex was safe and motor racing was dangerous. I fixed safety in the second; some of you are now responsible for the other bit.”

Knighted in 2001 for services to motor racing, Stewart retired in 1973 one race shy of his 100th Grand Prix after the fatal crash of teammate François Cevert during practice. His record stands at three world championships, 27 wins and 43 podium finishes in 99 starts at a time when racers had more than a 50:50 chance of getting killed on the track.

jackie_stewart_at_the_2018_goodwood_revival.jpg

At the 1966 Belgian Grand Prix in Spa, half the field crashed out during the first lap thanks to a torrential downpour, green flags condoning conditions that would be considered appalling today. Stewart’s BRM P261 smashed into a telephone pole and landed in a ditch with him trapped upside down in the car, soaking in fuel for 25 minutes while two other racers rescued him with a spectators’ toolkit. They were just one spark away from being part of a fireball. His last and record-setting 27th victory was at the formidable Nürburgring, which he nicknamed The Green Hell. “When I left home for the German Grand Prix, I always used to pause at the end of the driveway and take a long look back. I was never sure I’d come home again,” he said.

After Cevert’s death, Stewart campaigned furiously for decades to improve motor racing safety, which saw him derided and distinctly unpopular with race organisers, track owners, governing bodies and even journalists. He eventually gained the support of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association, of which he was chairman, and led boycotts of races at Spa and the Nürburgring, tracks with notoriously diabolical safety standards. Features now taken for granted — strategic barriers for run-off areas, proper marshalling and advanced medical facilities — are his legacy.

“Motorsport is popular because it’s so relatable, so many people drive, but there’s also glamour and power,” says the Flying Scot. “We don’t need to see death, death is ugly. A football player trips and he’s out of the game. Here, you have accidents going at 150 miles an hour, and the danger of man and machine is exciting. But to finish first, first you must finish. That comes down to your skills, the precision of your mechanics and the reliability of your cars. I needed better mechanics so I found the best people. That’s the way to go about business: commitment, concentration and human relationships.”

A broken nose at 14 inadvertently taught him these vital lessons, determining values that would forge a remarkable career and life. As his dyslexia invited cruelty at school, Stewart fell in with the wrong crowd. After an evening at a billiards room — “which in those days in Scotland were scandal-ridden” — he was walking out to catch a bus home when he was attacked by five men.

“They broke my nose, my collarbone … ” he recalls. “When my father saw me, he asked, ‘Where have you been?’ and I said, ‘I was in the billiards room.’ ‘Why were you there?’ ‘My friends were there.’ And then he said something very important: ‘If you fly with the crows, you’re liable to be shot at because crows are vermin. Soar with the eagles.’

“I have two boys and I tell them the same thing. You need to hang out with and learn from the right people. The most impressive people I ever knew were King Hussein of Jordan and Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth. It just so happens they are monarchs, but that has nothing to do with it. King Hussein was one of my best friends and I think I was one of his. He was a very good man, very calm, and a great enthusiast of motorsport. The Queen is just remarkable. She had to carry the monarchy from a very young age and continues to do it in a wonderful fashion.”

Ever since that fateful day at 14, the “master of going faster”, as George Harrison lyrically immortalised in Faster, has favoured quality in everything he does.

“I always go for blue-chip. I’m with Heineken now, I’ve been with Moët & Chandon for 50 years and Rolex for 51. I don’t know many people in sports who have the same commercial relationship with a brand for more than 50 years,” he says, slipping off his gold Rolex to point out an engraving on the caseback: ‘Thank you, Jackie, from Rolex,’ dated 2007. “I brought six watches to the Singapore Grand Prix.”

“All Rolex?” asks a journalist, to which Stewart laughs, “Is there another watch company? I wear a different one every day and night. I have a new Daytona in stainless steel, a rose gold Daytona, a Day-Date in white gold, Day-Date with a green face and leather strap and a Daytona with a blue face and matching strap. I was paid a lot of money to do Indianapolis in 1966, so I bought my first Rolex, a gold Day-Date with a president bracelet. I became a brand ambassador two years later.”

schlegelmilch72pr-tour-d004-copy.jpg

His relationship with Rolex is just six years younger than his greatest collaboration: his marriage. Helen, the original pit lane girl and a stalwart by his side throughout the ensuing highs and lows, is currently seeking treatment for dementia in Switzerland. Helping her has returned to Stewart the same vigour he had in racing, from updating their Lake Geneva home to be dementa-friendly to founding the Race against Dementia charity and investing £2 million in academic scholarships to find a cure. “He attacked it like he was back on the track. Dementia is the opponent and he’s determined to beat it,” said his film producer son Mark in a 2018 interview.

“You have to go for the top-end in the company and partnerships you choose,” says Stewart. “I’ve been married for 57 years. If you’re single, find someone who is all the right things — they have to be blue-chip.”

He seemed to be referencing Helen. She would probably say the same about him.

This article first appeared on Oct 28, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.