Lionel Messi winning the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 (Photo: Reuters)

"Football: taking human beings to places they can’t imagine” was how commentator Peter Drury described the contrasting reactions when Italy saved themselves and knocked Croatia out of the European Championships with almost the last kick of their group game.

It was ecstasy and despair in equal measures — something that only sport can deliver not just to teams but entire nations. It’s only a game we are told, and doesn’t matter in the great scheme of things. But those of us embarking on another Olympic viewing vigil — after barely catching our breath since the Euros and Wimbledon — beg to differ.

Here in Malaysia, it matters: Just wait till our gold drought is finally broken and you’ll see human beings in some unimaginable places. We may not be great at the moment, but can take pride in having punched above our weight in sports that were long denied a place on the biggest stage. Sport may not be life and death, but even in a troubled world, it carries a value far higher than the gazillion-dollar industry it has spawned. It is the raison d’etre for many, football alone having more followers than the two biggest religions combined.

Participation, you might say, is a different ball game whose benefits to physical fitness and overall well-being go without saying. But it’s beyond the playing field where sport becomes a global language that can break down barriers and even bring societal change. Its importance was shown during the pandemic by the strenuous efforts some countries made to maintain sporting events — even behind closed doors — to keep the population entertained. Its priceless ability to boost morale is why war-torn Ukraine encourages its footballers to carry on playing for their clubs and their country at the Euros, and its tennis players to go to Wimbledon. “You can make our country prouder by playing on the football field than on the battlefield,” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky told the national team.

The logic is that they’re no better than the next man with a gun, but on the pitch, they can lift a nation. Countries have always protected their celebrities but where Ukraine differs is in allowing its domestic league to continue as well.

Chelsea midfielder Mykhailo Mudryk is safely ensconced in the English Premier League (EPL) but has not found the special dispensation easy: “I’m playing football while my city [Krasnograd] is being bombed day and night,” he noted as the Euros kicked off.

Football and war are no strangers. In 1970, a four-day conflict between Central American neighbours Honduras and El Salvador was known as the Football War. A feisty World Cup qualifier between them sparked a pitch invasion before a real invasion days later.

Yet it was football that almost brought a halt to WWI when the guns fell silent for the Christmas truce. Warily, British and German troops left the trenches to exchange cigarettes and chitchat. Then someone brought a ball and before you could say “Fire!”, a game started. With the bonhomie spreading along the front, the generals had to blow the whistle so hostilities could resume.

Adolf Hitler tried to use the Berlin Olympics to show off what he believed was “Aryan superiority” only to tee up one of his greatest embarrassments. Black Americans were not granted full status by the hosts who classed them as “auxiliaries”, but that didn’t stop Jesse Owens from turning in one of the greatest Olympic performances of all time.

1936-01-01t000000z_1797112974_mt1imgosp000rf7gf1_rtrmadp_3_imago-images-sports_reuters.jpg

The distinctly non-Aryan sharecropper’s son became the first American to win the long jump, 100m, 200m (in a world record time) and 4x100m relay in the Games.

If that wasn’t enough to make the führer furious, Owens’ blond German opponent in the long jump, Luz Long, went out of his way to assist Owens in his preparation and became a lifelong friend. It didn’t stop Hitler but it was an eye-opener for people in the US’ deep south — on both sides of the racial divide.

Sport was a phony battlefield during the Cold War, too. Desperate to top the US’ Olympic medals tally, the Soviet Union and East Germany waged a kind of proxy war. The weapon of choice was drugs that turned women into people that might flout the gender test today.

The sheer magnitude of the Olympics has made it a prime political target — unlike its ancient ancestor that declared “an Olympic truce” between any warring states for the duration of the Games. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has finally followed but it came too late to prevent a rancorous couple of decades.

The most shocking incident of the modern era was the 1972 massacre of 11 Israeli athletes by the Black September militant Palestinian group in Munich. The 1970s and 1980s were a troubled era for the Games, culminating in the tit-for-tat boycotts in 1980 (Moscow) and 1984 (Los Angeles).

It may be a back-handed compliment but it could be argued that sport’s importance has never been greater: when the Russians invaded Afghanistan, the US’ instant response was to wield its most powerful non-lethal weapon — an Olympic boycott.

Malaysia was one of 67 countries that snubbed Moscow and, as sure as night follows day, the Soviet Union reciprocated four years later. But it could muster just 13 supportive satellite states who stayed away from Los Angeles, although the Games was still the loser.

1986 saw a boycott of the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh with 32 of the 59 nations staying away because of Britain’s sporting links with apartheid South Africa.

With the ending of the Cold War and apartheid, the big sporting extravaganzas became popular again towards the end of the 20th century — perhaps too popular. A new problem was the lengths bidding countries would go to — and amounts they would spend — to play host.

So, instead of political shenanigans, the new blight was the stench of corruption and creation of white elephants — single-use facilities that cost a fortune. But this trend is now being curbed, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s Sochi excesses apart.

Cricket may seem an unlikely source of conflict, but India and Pakistan observe a nuclear standoff when it comes to test matches although they do meet in 50-over and T20 tournaments. And England and Australia once had a most ungentlemanly spat in the 1930s.

Australia had a genius batsman, Don Bradman, and England countered with demon fast bowlers who didn’t always aim at the wicket. After a few nasty blows, Australia cried foul and thought of quitting the British Empire! It took WWII to bring them together again.

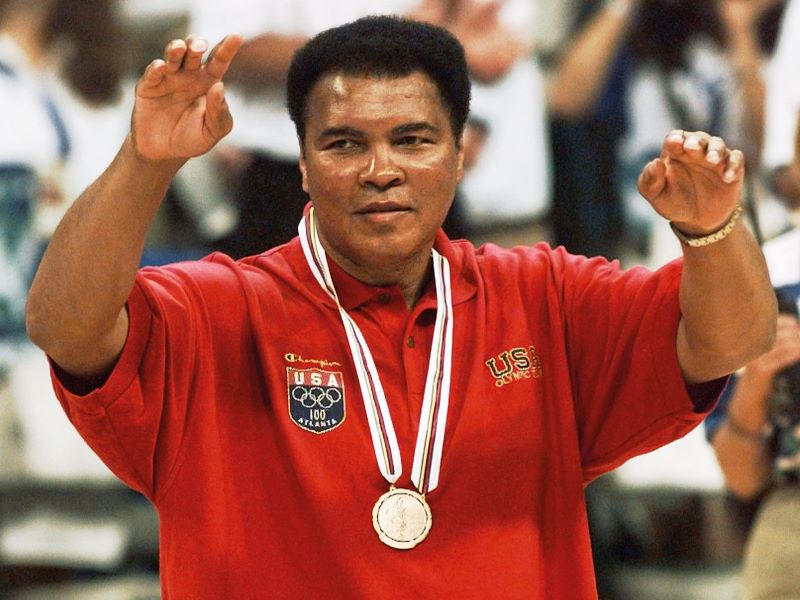

1996-08-04t000000z_1646357641_pbeahumwfae_rtrmadp_3_ali_reuters.jpg

It’s not always been about national pride as certain individuals get worshipped across the boundaries. The likes of Pele, Diego Maradona, Jesse Owens and Muhammad Ali and, more recently, Tiger Woods and Lionel Messi have been among the most famous people on the planet, better known than their national leaders.

But when it comes to influencing world events, nothing can match what will forever be termed ping-pong diplomacy. It began when the US’ table tennis team, touring Japan in 1971, received a surprise invitation to visit China. The last contact of any kind between the two countries had been in 1949.

The team duly accepted and the trip was a success, paving the way for visits by US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and, finally, president Richard Nixon’s famous meeting with Mao Zedong.

It was a sensational and totally unexpected breakthrough in US-Sino relations, which became quite friendly until the recent cooling. And it was sport that started the ball rolling. Perhaps they should play again.

There’s no question about sport’s impact; it is way more than a mere pastime, encourages unity and breaks down barriers. It has a multi-faceted significance to both the individual and team. And in a troubled world populated by a self-centred generation, it has never been more important.

This article first appeared on Jul 22, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.