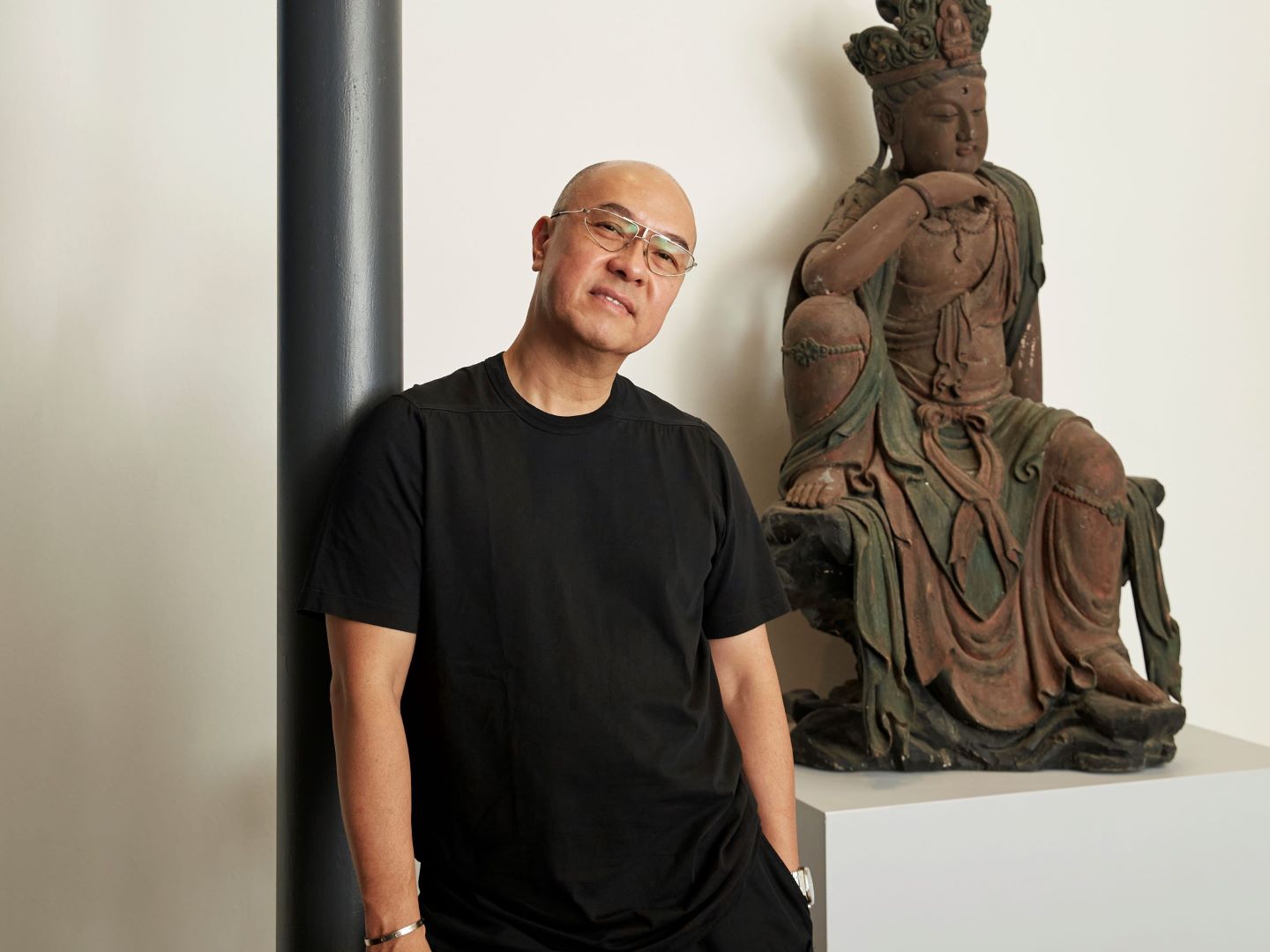

Returning to Malaysia after 30 years, Leong Kwong Yee encourages new narratives in his contemporary space (Photo: SooPhye)

The Return of Raja Durian (TRRD) is the kind of show Leong Kwong Yee envisioned when he set up Blank Canvas in George Town two years ago. “Its mission is to show different forms of contemporary art.

“We’ve always had a tradition of art, but when I came back to Penang during Covid, I thought it was very much centred around paintings and 2D works. When I looked at contemporary art, I felt there really was a gap because that’s also my passion.

“I’ve been trying to expand into performance, sculpture, temporal, video, to [widen] the language of contemporary art. Every exhibition we put up shows a different kind of art practice as well as those from different parts of the world,” says Leong.

TRRD, which opens at his art space on Nov 16, nails that. It introduces visitors to campy Fameme, who literally bursts into New York’s social scene with the launch of the Museum of Durian at SoHo in 2019.

Taiwanese artist and filmmaker Yu Cheng-Ta first meets him at this event.

With his oversized sunglasses and colourful suits, Fameme is flashy and as thorny as the tropical fruit he flaunts while dancing down the street, surrounded by bright lights and giant billboards. The Asian billionaire farmer is promoting the durian, in the hope that it will gain him fame and acceptance in American culture.

In the spring of 2020, Fameme opens the Durian Exercise Room at the Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art in South Korea. That summer, he launches the Durian Pharmaceutical in Taipei Fine Art Museum. At this event, he reveals the Misohthornii, a nutrient he extracted from durians using his own strategy. His company has applied for a patent for MST, a custom-made, contemporary elixir of life, which he plans to introduce by 2023.

Enterprising and always ready to seize opportunity, he has also released a Spotify song and a music video in Japan.

Fast forward to 2024 and Yu has produced a new documentary on Fameme’s personal history, his relationship with his family and struggles with self-identity as he carves out his own durian empire. The film marks a homecoming for the little-known figure in Penang and will be screened for the first time at Blank Canvas.

With this project, Yu explores the cultural phenomenon of “influencers” in Western social media, alongside celebrity and food trends in a series of live and filmed performances that appropriate the visual and narrative language of reality TV. Fameme jumps right in, using the latest marketing trends and milking media obsession for capitalist gain.

Leong had met Yu in Hong Kong years ago through a friend, also a performance artist. “Fameme’s behaviour is a [reaction] to what he saw at that time about East and West, and how people perceived modern-day Asia. This was the period of Crazy Rich Asians. There were a lot of perceptions and he was responding to this particular Western understanding or exotic view of what Asians are.”

Fameme’s name is a play on meme and he keeps pushing social media culture, using the durian, probably the most exotic fruit you can get from Asia, as a symbol of Asian exoticism, adds Leong, who does not eat the fruit himself. “It’s smelly yet many people respond to it.”

“When I met Yu, I went like, ‘If you’re talking about durian, you have to come to Penang’. We all agree it has the best fruits in Asia. We like to believe that.

“Fameme has a really strong backstory. So we invited Cheng-Ta to Penang, where he did research on durian farming and industries in the state.” His first visit was in May last year and the documentary was filmed over nine months.

2._the_return_of_raja_durian_fameme_1.jpg

On top of this, there will be an exhibition of a collection of objects and documents that reveal the vicissitudes of Fameme’s history and how he transformed his family’s business. It is co-curated by Yu and Singaporean art historian Louis Ho. A day after the opening, visitors will get to hear Yu talk about his experience of working with Fameme.

On how TRRD got its name, Leong explains: “Fameme is from this part of the world and there is family drama [in his life]. He has tried to become popular in other parts of the world and is now going back to his roots.”

He thinks many Asians can connect with this narrative, and is reminded of how his own life has panned out.

“I left Malaysia a long time ago. Now I’m back and getting to know my country again. A lot of us can identify with that story. It’s about love by the parent, or non-love, and having to leave your country to be popular elsewhere. But nobody knows who you are at home.

“I don’t think it’s so much about understanding the art. For us, the thing about contemporary art is this idea of understanding the story and being able to connect with it. It’s universal. And this connection between something that happened in New York but started in Penang is also very important for Blank Canvas.”

TRRD is a big project with the potential to draw eyeballs to Penang, thinks Leong, who has decided to stay. When he returned in the midst of Covid-19, it was a mainly practical move and an opportune time to lie low for a bit. After all, he left Malaysia at 19 and had been away for 30 years, travelling the world for work from his base in Paris and Asia.

It did not take long for this ardent collector of over two decades to notice his adopted hometown lacked a contemporary art space. Thus the birth of Blank Canvas in 2022.

“One of the things I don’t do is complain: ‘How come we don’t have this; how come we don’t have that?’ I could question till the cows come home … I’m very action-oriented. If I can do something, I do it.

“I never intended to start an institution. In fact, I’m still learning how to run this. I reacted to what was lacking and said, ‘Let’s do something’. That’s really the logic. And actually, because I had started Blank Canvas, I decided to stay.”

The inspiration behind its name is that Leong welcomes everybody to step in and use the space. “It’s not a gallery because we are not commercial. I wanted it to be open, collaborative.

“It’s really a place for everybody to participate, whether you are an artist, exhibitor or curator. The name contains the spirit of what I was thinking at that time. It still does. When an artist comes to work with us, they literally have a blank canvas. We don’t impose what they can or cannot do.”

Ultimately, he hopes this will lead to a wider understanding of art practice. “It’s not just paintings. I love a good painting but you could also look at video, sculpture, lives and narratives. I hope people also take away the fact that Penang can and should be connected to the world.”

Visitors to TRRD will see the connection between Penang and the Big Apple we heard about but which many have never been to. Conversely, there are Malaysians who have returned home after going all over the world. “I want people to see this global connection that Penang can have, or has. For foreigners who come, I hope they can understand the richness of

a local family.”

The island is where his mother hails from and logistically, it suits him better than off-the-grid Taiping, his birthplace, as he flies a lot. Leong is a management consultant who works for global multinational companies, many of them French luxury brands.

His experiential platform, which takes up a rental shophouse within George Town’s Unesco World Heritage zone, is non-profit. But what he gets in return adds up to “a big learning”, he says.

blank_canvas.jpg

“Blank Canvas acts very much like an art institution, which is lacking in Penang. I get something out of filling that void. For me it’s very important.

“I learnt a lot from the process, from conversations with artists. Our art handlers, the team, learn because every exhibition is different, every artist teaches us something about art practice. I’ve learnt. I collect. I exchange.”

There is also the satisfaction he gets from sharing what he calls “privilege” — that of seeing really great works all over the world.

“I’m very lucky I had an international career and lived in Paris. When I was growing up in Taiping, there was no opportunity to see many things. I would like people to have this experience I have had. I get a lot of pleasure from sharing.

“The more I engage with the international art world, I think the more important it is to highlight that uniqueness, without sort of ending there. Every region is unique and so is the work of its artists, from North America to India and South Korea. I just think it is not celebrated, not understood, not researched, and not preserved. How do you narrate it? How does it contribute to the rest of the conversation?

“We have Malaysians who have exhibited everywhere. Chang Fee Ming has travelled all over the world. Wong Hoy Cheong, whose seminal video installation work was first shown at the Venice Biennale, never really had an exhibition in Penang until we featured RE: Looking, 2002-2003, earlier this year.”

Leong’s interest in art was kindled 20 years ago when he “started a relationship with somebody who’s very different from me, and we decided to explore it. I was living in Hong Kong, which was beginning to have an art scene about then, when Chinese contemporary art became very global and Chinese artists became internationally known”.

What began as a hobby led to frequent visits to art shows and fairs and “moments of exchange and learning, and getting to know international artists”. And he started collecting.

wong_hoy_cheong_installation.jpg

Blank Canvas hosts four exhibitions every year and one of them is given to Leong’s art collection. Typically, he makes sure to encourage conversations between international and local artists. Or, a display could present something the team has never done before, such as the just-ended What It Is Of by France’s Éric Baudelaire, which investigates the existence of telekinesis.

“It’s about mind reading: I’m very drawn to things that are new to me and also audiences, so that sometimes forms the selection.”

The fun factor is crucial for Leong, the artist and viewer. He recalls a collaboration with Sputnikforest, a Penang-based spatial designer, who curates plants, not art, and came up with the concept of a forest without a single plant. He recorded his footsteps, so visitors could hear the sound of him walking into it and inhale its smell.

“The idea is also to create an exhibition that you feel rather than just see. We are too visually stimulated. Art should engage all our senses, including our feelings.”

Two years into running the show, literally, Leong talks about visitors being wowed by things they had never seen before, or a good friend, also an artist, who has been to all of Blank Canvas’ 10 shows telling him, “Okay, I think I’m getting it”.

Get what?

Leong, who did philosophy for his first degree, laughs. “The thing you discover about philosophy is, there are no answers. There are only questions, and the question is more important than the answer.”

What he hopes is visitors will leave asking themselves, “What am I learning? What is the thing that is meaningful for me? What can I do?”

They could attend an exhibition or ask friends to go. “We’ve had people who write for us and come to our show, or broadcast it on social media.” Support could be hosting a dinner for visiting artists or even putting them up for a stay.

Art spaces cannot depend on a single fund agency or government help alone. “All the museums have different funding mechanisms; so does Blank Canvas.” TRRD is supported by Taiwan’s Ministry of Culture and the Taiwan Content Plan.

The question he poses to collectors, who seem to be buying and buying and sitting on a lot of great works or placing them in warehouses is, “What are you going to do with them? How does this inform your life?”

Leong goes for a wide range of work, from paintings to photography and sculptures. With conversations on sustainability getting more urgent, he is looking to art that minimises the use of materials.

“You know, a work is created through earth and it rots. After that, it creates mushrooms. And then the mushrooms go back to the earth and are reincarnated. These sorts of practices are very interesting to me at the moment.

“I guess it goes back to our Asian tradition, where things are very organic. I was trying to remember when I was young, when we tapau food using newspaper with the banana leaf inside. There was very little wastage.”

He is also drawn to artists who not only shout eco-sustainability but also walk the talk. At his last collection show, one of the artists, following his usual practice, recycled the materials used in his work. “That’s incredible.”

Performance art, as well as projects that tackle identity and other big topics attract him too. “But my interest changes, grows with conversation. I don’t have a fixed thing that I collect.”

Young artists have a place at Blank Canvas, as it offers internship programmes open to all, which Leong hopes can help expand the vocabulary of contemporary art. He observes that art here is still very much tied to painting practices. “I think they are more experimental in other places.”

Looking beyond brush and paint, he sees the need to widen and build up the support structure that makes art work. “It’s not just about the artists. They can produce the work, but a curator needs to create an exhibition. Then a writer has to write about it. We need a whole ecosystem. That’s why we host a curatorial residency.

“In a more developed system, each person contributes. But we don’t have this division of labour because we don’t have enough people, so [artists] do everything. I really want to encourage people to expand this narrative.”

Blank Canvas is a huge commitment for Leong, one he wants to keep, he assures. “I’m committed to making it part of Penang. I’m Malaysian, so there’s always a part of me there.”

That is Leong’s short reply to whether he will stay on in the island and do work for, and with, art. The long answer, he adds, is his space evolves. “It’s beyond Penang. It would be nice to also show Blank Canvas internationally. I don’t know how to do that, but I’m open.”

'The Return of Raja Durian' runs until Feb 9, 2025.

This article first appeared on Nov 25, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.