Chen also dreams of opening daycare centres for the elderly; nursing homes where those with no one to look after them can stay after they are discharged (Photography by SooPhye)

Patients who ask Mary Chen what she does at Beacon Hospital do a double take when she gives them a straight answer. When they find their tongue, the usual reaction is, “Haah? Founder ah?” Then, to emphasise their incredulity, they add that she could pass for their neighbour.

The homely association is not surprising as those warded at the cancer specialist hospital would have met executive director Chen as she goes on her daily rounds after office hours, to chat with and comfort patients, often lending them a shoulder to cry on.

“People cry because they can see we really help, not just talk. It is very important for patients to have peace. I always tell my staff to treat all of them like their brother, sister, mother or father. If we use our heart to treat, it is a different service already. If a patient cannot swallow, I will tell her, ‘Okay, my cafeteria will bring you some soup this afternoon. You must finish it ah, it’s very expensive’ — to make her eat.”

Empathy for those whose lives have been turned upside down by illness makes her cry with them. “Cannot tahan,” says Chen. “They have no choice and I really can’t do anything. So I try to give them love.”

Hers is a practical affection, manifested in cutting-edge facilities housed in a hospital originally established 14 years ago as Wijaya International Medical Centre. The man behind it, Datuk Seri Tiong King Sing, invested almost RM100 million to bring hi-tech equipment into Malaysia to treat cancer.

Chen took over the hospital in November 2010 and renamed it Beacon, as suggested by medical director Datuk Dr Mohamed Ibrahim Abdul Wahid.

“I did not understand what a beacon is. They said at the seaside, you have the light [in] the darkness. Suddenly, in my mind, I thought, okay lor, because when a person is first diagnosed with cancer, the world becomes very dark for him — there is no hope. So Beacon comes in to give light by providing the top doctors, machines and service.”

Chen soon learnt that the best equipment is of little use to those who cannot afford to pay. “The poor patients told me, ‘You have everything [that is] top, top, top but they are not relevant to us’. So I came up with corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes so they can have the same high-quality treatment as the rich.

“I’m a Christian and I can say God has led me on this journey together with all the right people. He makes me intelligent, so I know strategy and what to do. No one in our team had experience in the medical line. Today, we can help people and be a good hospital. But it was not because of one person’s work.”

When Chen was first approached by a childhood friend to run the hospital, she did not feel equal to the task. “I am only a primary school leaver and my English is poor. How could I manage the specialist doctors and nurses?”

She said no, but the friend persisted. “She told me every time she prayed, she saw me. Maybe it was a calling.” To do or not to do? Indecision kept her up at night until she changed her mind.

beacon_hospital_main.jpg

Her next move was to get her elder brother Aaron to invest in the hospital. The siblings had set up an electrical goods business in 1989 and diversified into other areas, such as industrial supplies, trading and food and beverage under the umbrella of KVC Group.

Aaron responded to her idea with four words: “You must be crazy!” A dejected Chen could not sleep a wink that night.

When she approached him again the following morning, he explained: “I do not want to earn money from people who are sick, whether they have money or not.”

She suggested that perhaps they could earn some money and use it to help the poor. “I told him I would use love to run the hospital. When he heard that, he said to go ahead and has supported me until today.”

The next person Chen roped in was Victor Chia, a primary school friend who has been her business partner for more than 20 years. She convinced him to take charge as CEO and they plunged into the venture that would put them in the red for the next eight years. “For the first five years, our salary was paid for by our other businesses.”

Profit-making is not the first priority at Beacon and it does not strive for a six-star environment, Chen says. “Other than staff salaries and benefits — they have their own commitments — we operate on a lean budget. Even our consultants are willing to travel economy class for our CSR programmes, although they fly business personally.”

There are 345 staff members and many of those in the senior management team are long-serving employees who understand the company’s philo sophy of working together, managing together and sharing together.

Chia anticipates that medical costs will go up every year. He hopes some of Beacon’s strategies — such as halving the price of FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose, a radioactive drug or tracer used in PET-CT scans), which it supplies to two private hospitals, and then asking them to lower the cost of their scans by the same percentage— will make a difference.

“We hope that one day people can say, ‘We still need to treat but the cost is not so high’.” Chen adds, “If we drop our prices and other hospitals also do that, I would be so happy. I want that to happen. Let the patients go there, it’s no problem”.

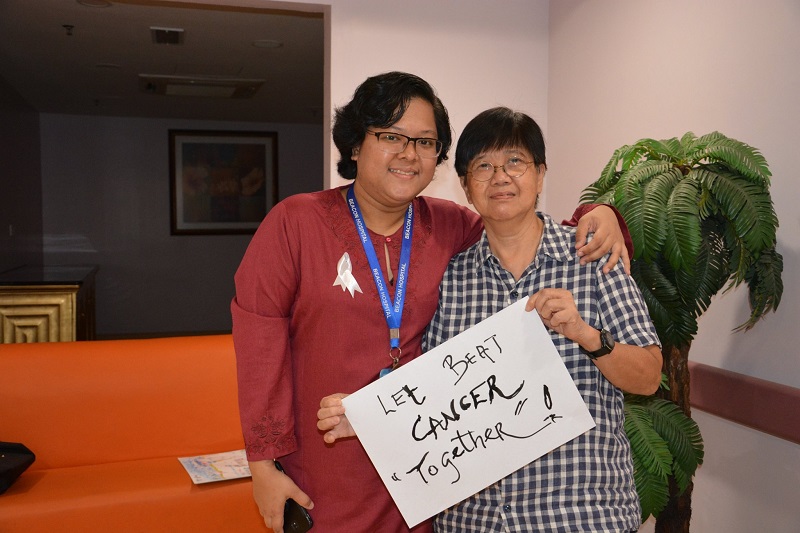

48355788_2384943088191493_5066091428040409088_o.jpg

Concerned that prohibitive costs often hold patients back from seeking treatment when they cannot afford to wait, her rule of thumb is to place medication before payment.

“I want to make it simple because when people come here, their hopes are very high. If suddenly there is no hope, how would they feel? Patients cannot have no hope because the cancer cells come up again, faster. So I always tell them, ‘Don’t worry about money. See how much you have, you give. If you really don’t have, we will see how to help.”

Yes, there are people who have taken advantage. “Not many, and it’s still worth it. You cannot make things very strict because of these few per cent. If you have a lot of terms and conditions, better don’t give, I feel. So I always tell the CSR team: ‘Treat first, then we will see how many per cent [discount] we want to give later’.

“We treat our CSR patients like VIPs because we want them to feel that they are not in third class. Even if you have no money to pay, you get the same treatment. It’s our service.”

A result of this heartfelt care is patients who are reluctant to go home upon discharge. “Where got like that?”, Chen laughs. Others tell her they will come back and visit. And there are those who remember the biscuits, tea and coffee at the out-patient lounges, courtesy of an F&B chain under KVC, fried noodles, rice, vegetables and chicken for those doing health screening, or the 10 vehicles on standby to transport the elderly to and from the hospital for eye treatment, some under a subsidised cataract surgery scheme introduced this year. “But only one eye each, so two people can benefit,” Chen says.

Placing the well-being of others first comes naturally to her. She was born in 1962, the second of seven children and the oldest girl. Her father was a construction worker and her mother a rubber tapper.

“I want to help. I have always thought like this, from young until now — how to help my brothers and sisters get a good education and afford good things.” Working towards that led her through some surprising turns.

At 12 years old, she left her Semenyih, Selangor, home to work with a family in Kuala Lumpur, taking care of three small children. “I stopped studying and went out to work because my parents really had no money.”

After 1½ years, she returned home and took up sewing. “As a servant, you always walk behind. I was very uncomfort able following people from behind. I thought if I can sew, I could open a shop and become a boss. I did not want to be behind. Maybe I’m a born leader. In class, I was the monitor.”

A year into sewing, she saw her boss being paid RM60 for three pieces of clothing that required more than a day’s work. “I calculated: RM60 x 30. If you don’t work, you get only RM1,000 plus. How to become rich and help people? So I ran away lor.”

Her next job was at a garment factory in KL, where she sewed pants from morning to night. She was the first to arrive and the last to leave. There was no EPF or Socso but she could earn RM1,500 to RM1,800 a month, which she sent home. “I only kept about RM100 for rent and meals. Four or five of us slept in one room, on the floor with no bed. Food was very cheap — 60 sen for rice with one vege and kuah.”

Three years later, she decided it was time to get a boyfriend, a businessman. “So must work in an office mah, only then can meet the boss and other people.” She learnt typing and was hired by a small welding business after telling them she could do office work.

But Chen had to handle the accounts, which she knew nothing about. “They asked me to write a cheque and I didn’t know how to do it. So, I got my Form Four sister to write out the words one to one thousand for me. After that, whenever I had to write a cheque, I copied the words one by one.”

She picked up the essentials but stayed for only three months because the work environment was dirty. “Also, no boyfriend to find.”

cancer_survivor_day.jpg

More confident now, she told friends she could do a full set of accounts and landed a job at an electrical company. For the next six months, she threw herself into balance sheets and the whole works. To equip herself further, she signed up for night classes and took exams for three levels of the LCCI course.

“I tried all the past 20 years’ papers and practised till I knew how to do all the questions. I got distinctions for every level.” More importantly, she met her life partner when he walked into her workplace with supplies for electrical installations.

Quick to take the lead, Chen persuaded Aaron, who was then with a bank, to learn the ropes of business. “I told him that only business can change a whole family. He listened and came out to work with my husband.” Eventually, the siblings set up an electrical company. “My husband supported us — he gave me the goods but didn’t collect money first.”

Beacon is clearly a way for Chen to pay it forward. But she fights shy of publicity, preferring to keep a low profile. “I just want people to benefit and see their smiling faces.”

Her road to success is paved with hard work and dis cipline. “Not luck,” she says, “only blessings from God. But before the blessing, you must do what is right.”

How does she do it? “I wake up at 4am so I have more time. I spend one hour on Bible reading and prayers and another hour doing aerobics dance. My life is very systematic — I write down what I want to do, at what time.” After a hearty breakfast, she leaves the house at 7am. She has a snack mid-morning and a meal prepared by the cafeteria at 4pm. Chen, whose day ends at 9pm, skips dinner.

Weekends are solely for the family, adds the mother of four. Her two older boys are doctors; one is a management trainee at Beacon and the other, a medical officer attached to the orthopaedic department of a Klang hospital. The youngest boy is doing research at Harvard while his sister is a fashion designer in KL.

“They all work very hard and never use my money. They know how I have suffered.”

There is still lots to do, such as clinical trials and research aimed at improving cancer care. Chen dreams of opening daycare centres for the elderly; nursing homes where those with no one to look after them can stay after they are discharged; and CSR clinics in the rural areas for Malaysians and foreign workers. And she wants to set up a central kitchen to prepare nutritional breakfast and lunch packs which working adults can buy at a reasonable price.

With heart, mind and motive in the right place, nothing looks impossible for this do-gooder.

---

This cover story first appeared on Aug 12, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.