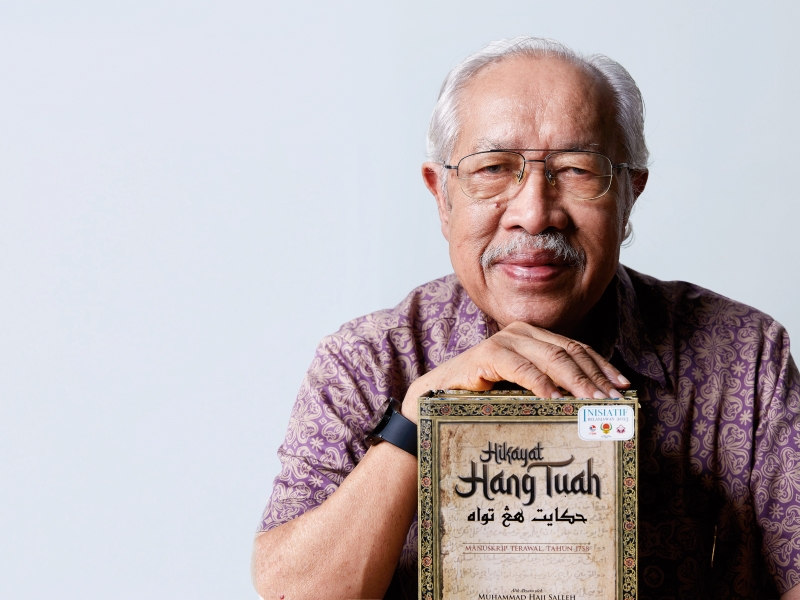

Decades of literary scholarship, research and writing seem to have only sharpened his mind, a storehouse of details about writers, books and stories (Photo: SooPhye)

By the end of the year, National Laureate Muhammad Haji Salleh will probably have 100 books to his name. It is an uplifting feat for the bilingual poet, translator and literary scholar, who makes no bones about writing.

“When I don’t have anything to do, I get depressed. Trying to overcome the depression takes me into the things I want to write. I start the day by writing poetry, editing or translating. If not, I’d be quite down. After working for so many years, suddenly it’s the end. So, I’ve found my way of solving my problems,” says the former academic, who turned 82 on March 26.

Prof Dr Muhammad brings a wealth of knowledge gathered from his work, travel and life to the table and into books. Retirement from teaching — the Brinsford Lodge, UK alumnus furthered his studies and taught at various universities at home and abroad between 1963 and 2005 — has given him more time for writing.

“There is also the luxury of being able to be with myself and my books. Some people don’t like books and don’t like themselves. They have to go out and find things to stay occupied. I don’t have that propensity to seek other people to give me pleasure, to take me away from myself.”

Quiet days at home are a welcome routine for this man of letters who, like most avid readers, has a favourite book and character. Again and again, he returns to the warrior Hang Tuah and rereads tales of his friendship and loyalty, told by different authors, of which he is one.

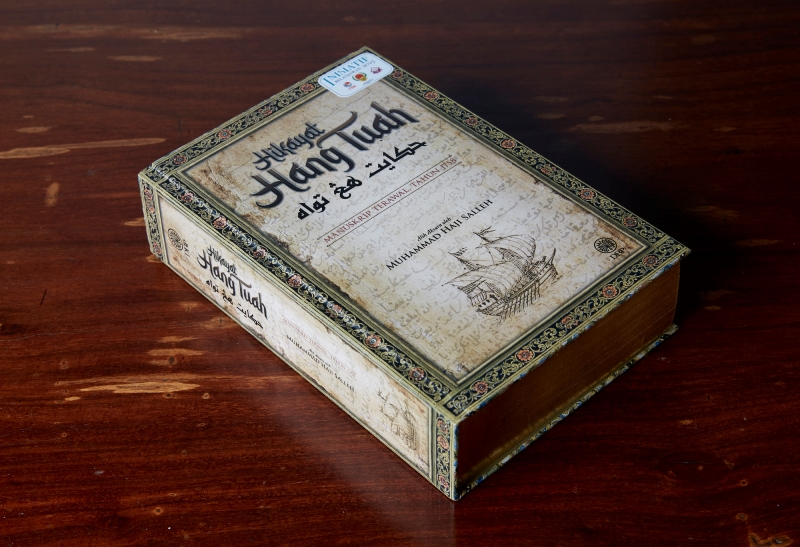

Over the last five years, Muhammad transliterated a 1758 manuscript of the Hikayat Hang Tuah into English. The tome published by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP) was launched last October in conjunction with the opening of the National Language Decade Carnival and the National Reading Decade. Several other books, including those by the Malaysian Institute of Translation & Books (ITBM) and private publishers, were launched as well by Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim under the 2023 Budget initiative.

“DBP wanted to have a really good-looking book. It’s big; hold it and you know you’re holding a great work, a karya agung,” he says. “People are now quarrelling over words, text, dates, characters and so on. This is the earliest manuscript, so it would be the defining one. It was all in Jawi; I transcribed it into rumi (Romanised Malay).”

_s1a9809a.jpg

Muhammad was chair of the Malay studies programme at the University of Leiden in 1993/94 and writer-in-residence in 2005. A good friend gave him a copy of the Leyden Manuscript but he sat on it because “I am not essentially a scholar of Malay classics. I’m a scholar of English, strangely”.

After his return from the Netherlands, “there was this decolonisation happening within myself and I noticed there were many good works comparable to Western texts. Something needed to be done. Of course, there were people doing it. But I had this idea that it was also my responsibility to transcribe them, to translate them.

“We all should be proud of our great works, help to spread the word about them, translate them into the main languages and, of course, study them. Whenever I have discussed the Hikayat Hang Tuah at international conferences, it has commanded special attention and interest. We should go further.”

A plan two decadees ago to collaborate on a translation with Alton Becker, a Fulbright exchange professor at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, fell through after he returned to the US. Becker suggested Muhammad proceed on his own, but the latter did not return to the project despite writing some papers and poems on the Hikayat or its episodes.

These last five years, “as a sense of guilt and age caught up with me, I reluctantly put my shoulder again to the great wheel of the epic narration”. He persuaded Rosemary Robson, then with the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies in Leiden, to help with the translation. “She filled up many gaps, the missing connectives and provided numerous fine turns of classical idioms.”

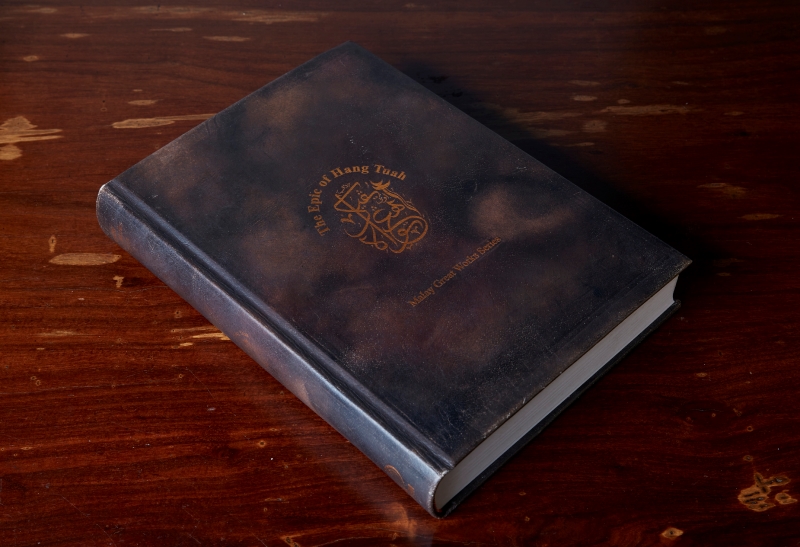

Muhammad himself is no stranger to Hang Tuah, said to have lived in 15th-century Melaka during the reign of Sultan Mansur Shah. In 2010, he translated The Epic of Hang Tuah (under the Malay Great Works series) from a book edited by Robson and Kassim Ahmad.

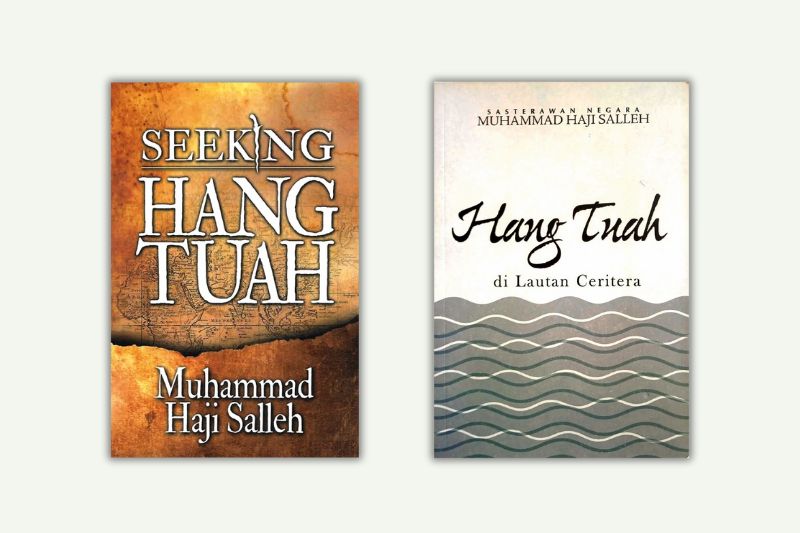

His Seeking Hang Tuah (2020) highlights the culture hero’s origins and journeys, values and qualities that have a place in the hearts of generations who grew up hearing accounts about the legendary warrior and his four friends, Hang Jebat, Hang Kasturi, Hang Lekir and Hang Lekiu. In Hang Tuah in the Ocean of Stories (2021), Muhammad takes readers on a long journey of Malay literature and heroes, with stops in Bentan, Melaka and Palembang.

With each book he worked on, he went deeper into the subject. “Have to lah; if not, you’d be repeating yourself. When you get older, you get deeper into yourself. That is quite nice, I think. And when you do it all over again, you [plumb] the depths, as it were”.

_s1a9811a.jpg

Travel is one thing Muhammad had in common with his subject and he rolled back the years to connect various destinations. “I travelled the world on the cheap when young, hitchhiking to Europe. Some of the places Tuah went to, I also visited, such as Rome. I could bring in my experiences and recreate his life and journey, his pleasures, disappointments, quarrels and, of course, friends. He had many because he could connect with others easily.” Tuah reputedly knew 11 languages, which took him into the palaces of the countries he visited. It was said he spoke Chinese when he went to China.

In the introduction to his latest work, Muhammad writes that for the last six centuries at least, Hang Tuah has been a model for young and old alike, helping Malays and people in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Brunei and Southern Thailand “define their social and moral ideals and giving them pride in their national identity”.

He adds: “Renewed passion for him and what he means surges to the surface when Malays feel threatened in one way or another, militarily or even economically.”

Tuah is our concept of the selfless hero who does not think about himself at all. He was twice accused of lèse-majesté against the sultan, who ordered that he be killed. But the bendahara wisely hid him away. When Jebat rebelled against the ruler, the latter realised he needed Tuah, and the court official was able to bring him back.

Some readers of this literary gem about patriotism, loyalty and sacrifice consider Jebat the real hero. What does Muhammad think?

“This is a tale of two heroes. I would like to see the Malaysian or the Malay in both Tuah and Jebat. They were loyal servants, but the subconscious also. And why not? Sometimes, we have to find a different guy who goes against the authorities. Jebat was a good man to start with. He went against the king to avenge his friend.”

When Jebat was nearing the end of his life, he went to Tuah’s house with one request: If a palace lady with whom he had had a relationship were to deliver a boy, please care for him.

“In the end, Tuah killed his friend. He had to because they were in a duel. It was very sad, very unfortunate. But it also reflected the philosophy of service and the subconscious. When the sultan did something wrong, Jebat fought him,” Muhammad says.

No one knows who wrote the Hikayat originally. “I have a feeling the Hang Tuah stories go round and round — accounts of this wonderfully loyal person who helped the town, the country and the sultan. I think there was a person called Tuah and I believe, as in this [version], he was an Orang Laut living south of Singapore,” he adds.

muhammad_haji_salleh_hang_tuah.jpg

“He grew up there but when life became too difficult, his father took the family to Bentan, as he heard it was possible to earn a good living. There, Tuah met the bendahara, who brought him to the sultan.

“For a few years now, literature has been pushed to the scrapyard of our contemporary life, giving space to technology and the sciences. We forget that these literary works are the products of our very own writers and their innovation. The Hikayat Hang Tuah, our greatest narrative work, pits him against his friend. They are both sides of the Malaysian character, values and institutions.”

As for why he is retelling an epic that has been recast fully or in part as movies, short stories, comics, musicals, plays or poems, Muhammad says: “I think we have forgotten our past. Now, our heroes are only the politicians. This is a tale far back in time that also illustrates what a real hero is — a selfless man who wants nothing and gets nothing.

“I am interested in the conscience of a person. A good human being cares about other people, our people and how we treat them or they treat us. Tuah is a fine example of a gentle, knowledgeable person educated by life itself.

“He walked around in the forests and palaces. He was happy that way. He didn’t have much, yet he shared. He helped others, was kind at heart and very polite — something very rare now.

“I seldom go to Kuala Lumpur. The last time I did, my God, our young people are barbarians! At the train stations, they langgar saja [collide with you]. You don’t expect respect because you are old, but there is right of way. If you read Hang Tuah, you can get something out of it.”

Would an anthology for children be one step in that gentle direction?

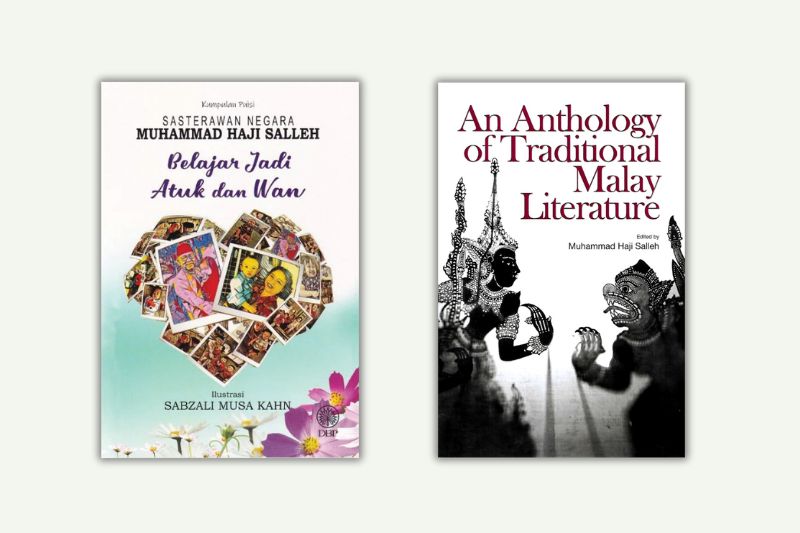

“Not yet. I’m not good when it comes to stories for children. I wrote some short poems for Belajar Jadi Atuk dan Wan. I don’t know whether people will read them but some of them are quite hilarious.” The book taps his experience of becoming a grandfather in 2012 and how the arrival of grandchildren brought him new and meaningful experiences.

Last year, he authored and edited An Anthology of Traditional Malay Literature and was involved in Cosmic Connections Langkawi, which brought art, science and poetry together on the same page. Muhammad wrote poems in Malay and English for the book; astrophysicist Tan Sri Dr Mazlan Othman was responsible for the photos of celestial objects taken from the Langkawi National Observatory; and artist Jalaini Abu Hassan did themed artistic sketches of the cosmos with bitumen and acrylic techniques.

muhammad_haji_salleh_hang_tuah_1.jpg

Muhammad kept himself busy as a writer and critic after retiring. “I found a place somewhere else but mostly did the same things.” The difference was not having to face students, a change he does not mind.

Always mulling new ideas in his head, he is looking to transcribe or translate oral stories because “I think they are due. These stories are our riches, not only the kelapa sawit”.

He has finished working on oral versions of the Hikayat Sri Rama and Hikayat Indraputra and will move on to poems for the Hikayat Hang Tuah after that. “When people get a chance to look at them, they will know these are from a thinking people committed to the good human being, very intelligent and very humorous.”

The oral stories are there, some collected in books or waiting to be told by the Orang Asli, of which there are many groups. “We took their land and didn’t give back anything,” says this former president of the Malaysian Folklore Society.

Intelligence and humour frame his work, though the line-up of his work looks serious. He spontaneously spins a verse after pointing to a table at his Kajang home in Selangor made from the wood of old trees buried in Selama. The town is close to Nibong Tebal, where he studied two years before the family moved to his mother’s village in Bukit Mertajam. All three are in Seberang Perai.

This eldest of eight siblings was born in Taiping but, with the war and Japanese Occupation, his family could not sell their rubber, so they moved to Sungai Acheh, Penang, and ran a sundry shop.

“My father was the kind of person who gave somebody something but never asked for the money. If you are a shopkeeper, you’ll go bankrupt quite soon.”

When that happened, they moved to Bukit Mertajam, where his parent brokered land, and they ploughed on. After that, he was the sole breadwinner for many years, first as a teacher in a trade school before venturing abroad to further his studies, teach, or take up residencies.

“I hopped from one place to the next, from Harvard to Leiden to Tokyo. Lucky me: I tell my friends it must be because of my good looks, nothing else. Also, I think [people] see a seriousness in me. I don’t beat around the bush or gallivant. And I wasn’t one to ponteng kerja.”

In time, recognition and reward came his way. It was sweet although not sought. When he was picked as Sasterawan Negara, he asked that the prize be delayed. “I accepted it only the following year, in 1991, because I thought only those over 50 should receive it.”

_s1a9853a.jpg

Looking back, he thinks the award helped him “carry Malaysian literature to the world. I am a recognised representative. No doubt I was chosen because I had written a good deal. But I must write and translate further. It’s all very demanding and necessary. I’m still at it”.

Decades of literary scholarship, research and writing seem to have only sharpened his mind, a storehouse of details about writers, books and stories. How does he do it?

“It comes from inside, from the responsibility to the great literature of the country. Who wants to do this? There’s no money — I don’t know how many copies this will sell,” Muhammad says, clutching the Hikayat Hang Tuah.

“But it should be there, in the best possible form. This is our literature, regardless of whether we are Malay, Chinese or Indian. It shouldn’t separate us but bring us together.”

Looking back on a lifetime of learning and writing, what is the most important thing he has gotten in return?

“Meeting the good minds and working with them. And the travel, of course. I was lucky to be introduced to some of the great works worldwide. I read Latin American literature; it was wonderful. I read Spanish, Greek, Russian, Chinese and even Japanese literature because I wanted to know about them. I took many courses, trying to fill the map of the world.”

Finally, translation, a lonely task, has helped build bridges that connect him with other writers and their work. “You’re alone with the text. You can imagine the author but he/she is not so close. There is always the challenge of staying true to the text, no doubt at all. ”

How about his autobiography? “Yes. I feel the writer should also have his history; he is the creative artist as well as the thinker of his nation. As I was given years of retirement I have made a good use of them to research, write and rewrite my autobiography. I have just finished checking the draft of Vol 7.”

The books trace his years of development from birth, important events, achievements and his life in the US, England, the Netherlands and Japan. “I have been to more than 70 countries, which I have written descriptions for.”

There could be eight or nine books eventually, which will bring his output past 100! Now, that’s what you call amassing a century.

This article first appeared on May 13, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.