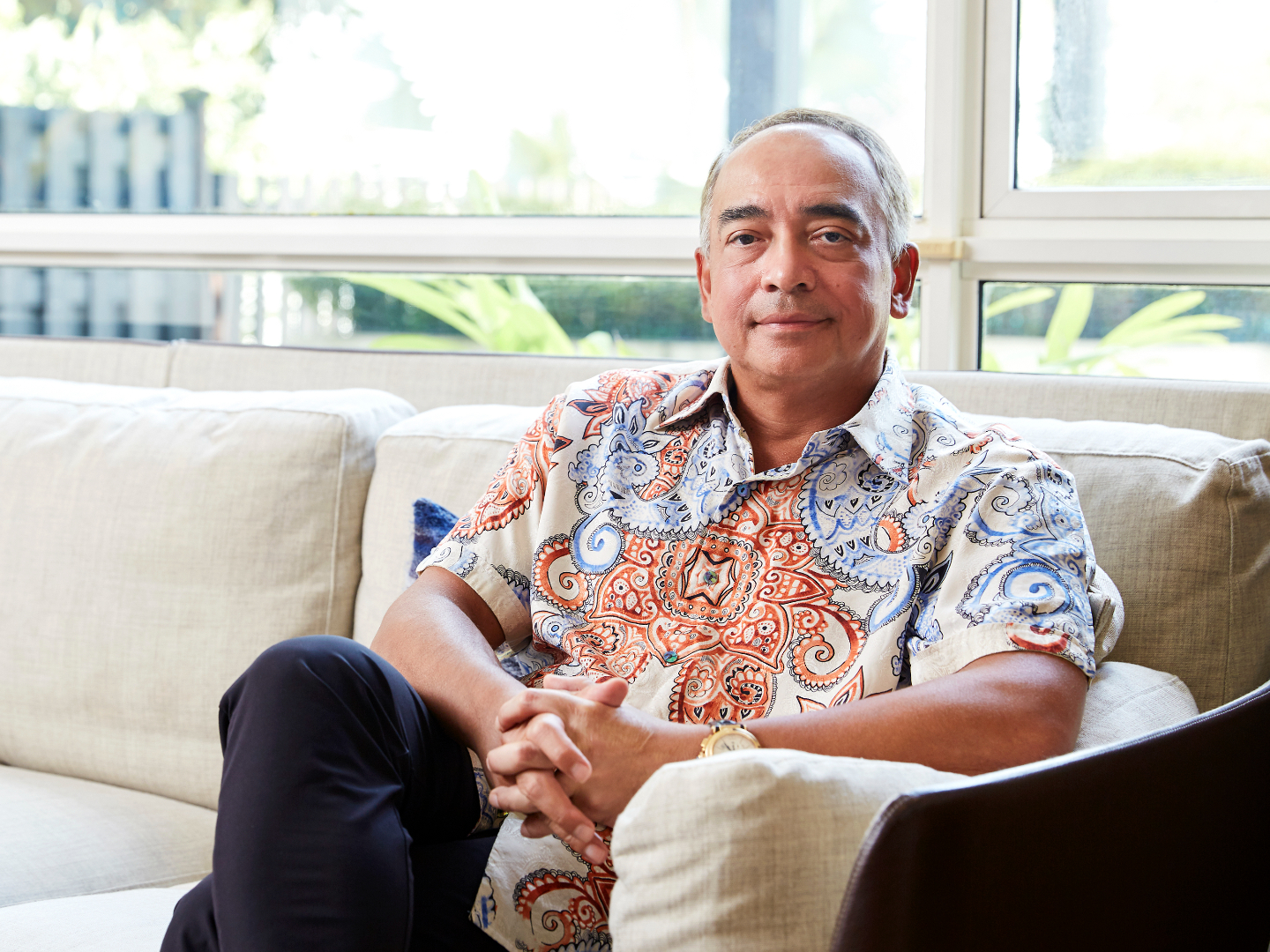

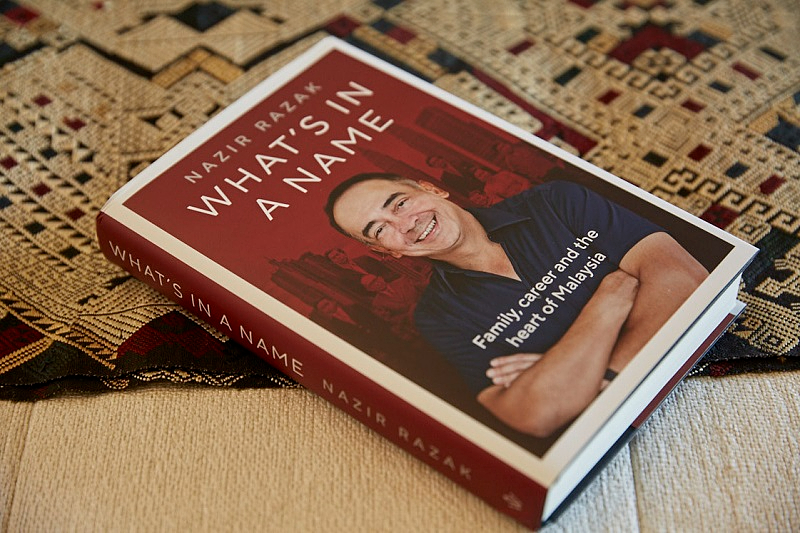

His book covers his father’s legacy and the changes in Corporate Malaysia (Photo: Soophye)

For years, Datuk Seri Nazir Razak resented the fact that after Tun Abdul Razak was diagnosed with leukaemia in 1969 and told he might have two years to live, he doubled down on work instead of spending more time with his family. The fifth and youngest son of Malaysia’s second prime minister has learnt that his father expended more effort than he realised.

While going through the New Straits Times’ archives to do research for his just-launched memoir, What’s in a Name, Nazir found “lots of photos of me and him, of us together at my birthday parties which I never remembered. I was so young and took things for granted — we don’t freeze those moments with our father because you think you will always have him.

“I better understood that despite his [duties], he did make a lot of effort to spend time with his kids. He was a much more engaging, caring father than I remembered.”

When Razak took a turn for the worse in London in December 1975, Nazir, did not get a chance to say goodbye. “I was resentful of that. Then I realised the reason was actually commercial — we didn’t have the money [to go].” Even Tun Rahah Mohd Noah could not be with her husband until the government flew her there. Sadly, Razak died on Jan 14, 1976, two months short of his 54th birthday, before his son could make the flight.

“I was nine then and don’t have many memories of my father. I had to talk to friends, family, those who worked with him, and read about him to write my book. I discovered a lot that I never knew about the person he was and got a better understanding of what he wanted, his values and motivations.”

Nazir’s memoir, subtitled Family, career and the heart of Malaysia, is sectioned in five parts: Remembering my father; Investment banker; Universal banker; 1MDB; and Conversations on Malaysia.

In 2018, he was asked to step down as chairman of CIMB Group Holdings Bhd, four years after taking the helm. Before that, he served as CEO for 15 years. He joined CIMB in 1989 and steered it from a top Malaysian investment bank to an Asean universal bank.

_s1a8640.jpg

Writing his book, at the right time, had always been on Nazir’s mind because Razak did not pen his memoirs. “It’s a very important medium for future generations to learn about right and wrong from the experience of others.”

Instead of an autobiography, he felt a memoir covering parts of his life relevant to two big themes — his father’s legacy and the changes in Corporate Malaysia, which he witnessed from the front row — would be less boring and regimented.

“To some extent, at a particular age, you want to leave something behind. I went through a lot in my life and career. When I began to write, I was able to think and reflect on the various events. When I really got going in mid-2019, while recovering from prostate cancer, I found it was a nice way to help the emotional healing. There were also the career emotions, the ups and downs, which the writing process really helped.”

With the benefit of hindsight, Nazir thinks Razak’s legacy is somewhat misunderstood: Malaysians focus too much on the tangibles (such as rural development, schools, universities, Malay-run businesses and buildings), whereas what is most important are the intangibles (such as values, principles, discipline, respect for others and self-confidence). “The institutions he set up and the policies he put in place must be understood in the context, especially post-May 13, of what was needed then. We should not defend them at all costs.

“My father’s values of being a democrat and a nation-builder would suggest to me that he would have expected us to review those tangibles needed for Malaysia at different times. In that context, what is I think a flaw today is we still very much have the system he put in place in the 1970s. Even the New Economic Policy (NEP), meant to be a 20-year thing, is still there after 50 years.”

Nazir urges Malaysians to ask: Are those things still relevant today, in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution? “The world has changed so much. As proud as I am of the tangibles my father left behind, I don’t think we should be hung up. We should do what’s best for the country today.”

There have been suggestions that he go into politics and walk the talk. “If I become a politician, I cannot walk the talk. Political parties and the system as it is would require me to do and say things I don’t fully believe in, just to survive.” That would compromise what he can articulate in terms of what he feels is best for the nation, Nazir adds.

nr02.jpg

He envisions different people having different roles in recalibrating or bettering the nation. His role is to speak his mind and contribute ideas, such as setting up a Better Malaysia Assembly, a definitive platform to debate and originate recommendations to set the country on a better path. “If such an assembly is indeed to be set up, I would definitely put my hand up. I desperately think it is needed and I would like to be a part of it.”

As for who should be in the assembly, Nazir says such platforms across the world usually comprise intellectuals, leaders and randomly selected members of the public — people who are truly independent and focused on what is best for the nation, not themselves or party politics.

Asked if he hopeful for the country, he says: “I am, in a sense that Malaysia has been able to pick itself up many times in the past. Remember we were brought to the edge by the Malayan Union? Even before that, at the end of the war, when the British were not here and there was chaos. And, of course, 1969 and then the Asian financial crisis.

“Malaysia has this ability to pick itself up. What is most important is that it’s not an entitlement — we have to fight for it. We have to bring people together to get it done. Unfortunately, this round, we are doing it a bit late. We have suffered more pain, more drag on the economy by retaining aspects of the system that have a sell-by date.”

Nazir singles out three ills plaguing the country: corruption, which is almost cultural and complex; the hardening of identities; and too much concentration of power.

Going back to the NEP, he says one can understand, at the macro level, the need to rebalance the economy. But at the micro level, when you have straight A’s and someone else with far inferior results gets the scholarship, it hardens your sense of deprivation and identity. “And you get the flip side of people saying, ‘I better identify myself with bumiputera because that’s how I get this preferential treatment’.

“We need a national reset. I’ve thought long and hard — I spent a year in Oxford thinking about this. I don’t think there is any other way.”

Nazir thinks it is not easy to fight for reform in a plural society because people can get lost in tribal arguments and forget what is really best for the country. “Sometimes, you can have something that is better for the nation, and everybody is better [off]. But you spend your time fighting about which community does slightly better and the whole idea collapses.”

_s1a8617_2ass.jpg

Things get more complicated when religion comes into the picture. “But you cannot take race and religion out of politics — and we don’t want to because that’s utopian. You have to have the right interpretations and part of it is also integration of people. This is where I think our education system is a problem.

“I completely understand the expansion and attraction of vernacular schools. But it’s a real problem that we all don’t go to school together. How do we square the circle to resolve that? I fully understand why bumiputeras feel the need for affirmative action. But what is the necessary form of affirmative action? It definitely is not what we have today, which benefits the minority of bumis rather than the majority.

“Religions are interpreted and I refuse to believe a religion as historically moderate and progressive as Islam needs to be seen as regressive and dismissive, as some people see it, or practise it. It’s about us embracing a notion of Islam that is not just right but also relevant to the nation.

“Malaysia is not an easy country. Plural societies are never easy, but you have to take it on. One needs to find democratic solutions for democracy to prevail. If you think about it, we did. Coming out of May 13, we had a long period of peace and stability. Now, those instruments that gave us long-term peace and stability need to be updated and reformed for Malaysia to go forward.”

As the man credited with transforming CIMB from a fledgling corporate finance franchise into a leading universal bank, was it painful to be told he had to leave?

“One must take a professional view because one can’t last forever. I was planning to leave at the end of my tenure in August 2019 anyway. What was disappointing was the speed and timing of it — October 2018, because I had requested to stay on at least until year-end so I could complete certain very important tasks for a four-year plan [T18, CIMB’s recalibration project].

“Zafrul (Tengku Datuk Seri Zafrul Aziz, then CIMB group CEO) and I were working on the next phase plan and it would have been a nice way to hand over to someone at the end of the year. But I was denied that. That was most disappointing, and I think it affected the momentum of the company.”

nr_55.jpg

Being a “very glass-half-full guy” who looks on the positive side, Nazir says he got over leaving CIMB very easily and wondered why. People even asked if he was bottling things up. “And I realised it was because being made to leave made it easier to leave — I didn’t desert my people. I didn’t have a choice.” Going around to say goodbye would have been much harder, he thinks.

Was leaving inevitable because his brother Datuk Seri Najib Razak had lost the general election in May that year?

“I’ve always had this view that at the end of the day, you need to have proper transitions for organisations.”

Did politics have a hand in all this? “I don’t know — nobody ever told me why. As far as I was told, ‘We no longer support you in this position.’ I’ve always said CIMB cannot be at odds with the government of the day.”

Since “retiring”, Nazir has picked up golf and is doing a lot of different things. He chairs Bank Pembangunan and, together with three partners, founded Ikhlas Capital, a private equity firm that invests in businesses across Southeast Asia. He also shares other setups with a couple of friends, one of which is a durian company.

“It is really, again, a bucket-list thing. You get so bogged down with banking and manufacturing companies that you totally neglect the exposure to agriculture. No, it’s not my favourite fruit but it has become an interesting fruit and an interesting business. I have learnt to enjoy durian more. I love the variety in my life now.”

In the section on 1Malaysia Development Bhd, Nazir covers in revealing detail how the saga unfolded over several years. “Obviously, I worked [behind the scenes] with Tong [Kooi Ong, owner and chairman of The Edge Media Group] and [Datuk Ho] Kay Tat [the publisher and CEO]. The fact is, there was this major financial scandal that was just wrong. I guess the painful part of it was at the helm of the government and kind of owning 1MDB was the minister of finance, a member of my family.

“Actually, it didn’t start that way. At the beginning, we thought everyone was on the same side — there’s something wrong here and we wanted it to be stopped. Unfortunately, that was when it diverged because Najib didn’t feel there was anything wrong. I did, we did, so then I ran into conflict with him, in that sense.”

How did the debacle affect the family, especially with his father’s good name dragged in?

“When you have tension between the family and your value system, first of all you deny it — you just cannot believe it. And it takes time to say, ‘Hey, you have to make a choice.’ It’s a painful process. I’m not sure whether everything I did was right but I chose that path and, in a way, it’s a funny path because you are kind of neither here nor there, as I described in the book.”

An option would have been to work openly with The Edge — “there was a request for me to join” — which was then investigating and writing about billions of dollars being siphoned off from 1MDB, a state-owned Malaysian investment fund. Caught in the moral maze and forced to choose between right and wrong, Nazir sought the advice of two ladies.

Ngaire Woods, dean of the Blavatnik School of Government in Oxford, of which he was an advisory board member, suggested that he remain in the background. She said: “Even the people who would back you now will never trust someone who could openly stab his brother.”

The second lady was former Cabinet minister Tan Sri Rafidah Aziz, who had worked under Razak. “She told me, ‘Your mother does not deserve this. You cannot publicly go against Najib because it would break her heart.’”

Faced with loyalty versus duty, this son of Abdul Razak made a choice that allowed him to look himself in the mirror and his mother in the eye.

“Family was everything to Mum and her unconditional love anchored all of us,” he says. “Whatever we did, we could always go back to the house, at all times. I just couldn’t be the one, at that juncture in her life, who forced her to see the division in the family.”

Nazir dedicates his memoir to Rahah, who passed on last December, aged 87. “For her, after my father died, it was all about bringing up these five kids. Her major project was that we must all get an education and a job. I remember asking her if I could stay one more year to do my master’s [in philosophy at Cambridge] and she said, ‘Hurry up. I just want this project completed.’ She was mighty relieved when I came back and we all got jobs.”

Rahah made sure none of her boys knew which one was her favourite and “she was very good at that”, Nazir says. “Everything was rule-based, in terms of what you got, and when.”

She bought all of them a second-hand car in their second year of university. He went to Bristol University, where he had to walk a distance to the lecture halls. “I pleaded with her to get the car in my first year. There was a family meeting over the exemption from the rule. I finally got it after about half a year of long walks every day up and down the hill.”

nr03.png

Mum knew all their favourite dishes and whenever the siblings visited her, it would be waiting. “When we were all there, the table would be full,” says Nazir, who likes fried chicken.

What legacy does he hope to leave his twins, Arman and Marissa? “I just want them to see and be proud of the life I led and the choices I made. I hope my name will not be in their way, whatever they want to do. If they decide to settle back in Malaysia, that’s not so easy. I hope at least those who recognise it will not hold it against them, either way.”

Nazir laments that he has never had a chance when it comes to first impressions. “Everybody I meet in Malaysia has a first impression of me. I build the second.” It has become second nature to him, when meeting someone, to look at them and suss out their preconceived notion of him, depending on their politics, background, age or whatever is most important to them.

He tries to make people “feel the side of me I think they need to see in order to understand me. It’s unfair but, face it, that towering Razak name. So, I might just have to send the message to say, ‘Look, maybe I am not the person you thought I was’”.

Being judged based on his name started early on, he adds. “In my interview with Shell, I walked in and the guy said, ‘How come you applied? Why don’t you just call the boss?’ On social media, people say things instinctively because Najib is my brother. They don’t bother to know me, to read what I write.”

Many people for many years thought he was CEO of CIMB because of who he was. “They would never bother to work out that I started as a rookie,” says Nazir, employee No 69 when he first joined the fledgling bank. In fact, he was rejected after his first interview because they “didn’t believe I could work hard enough to be in CIMB”.

Has his name been more of a privilege or disadvantage? “Honestly, I don’t think about it because how do you calculate the plusses and minuses? With privilege comes expectation.”

Prejudice is ingrained, he thinks. “It’s a natural instinct — we hire and hang out with people who are like us, with the same background. If we want to make the nation a success, we must all go against what comes naturally. If we are serious about being Malaysian, we must all fight against this.”

This article first appeared on Nov 15, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.