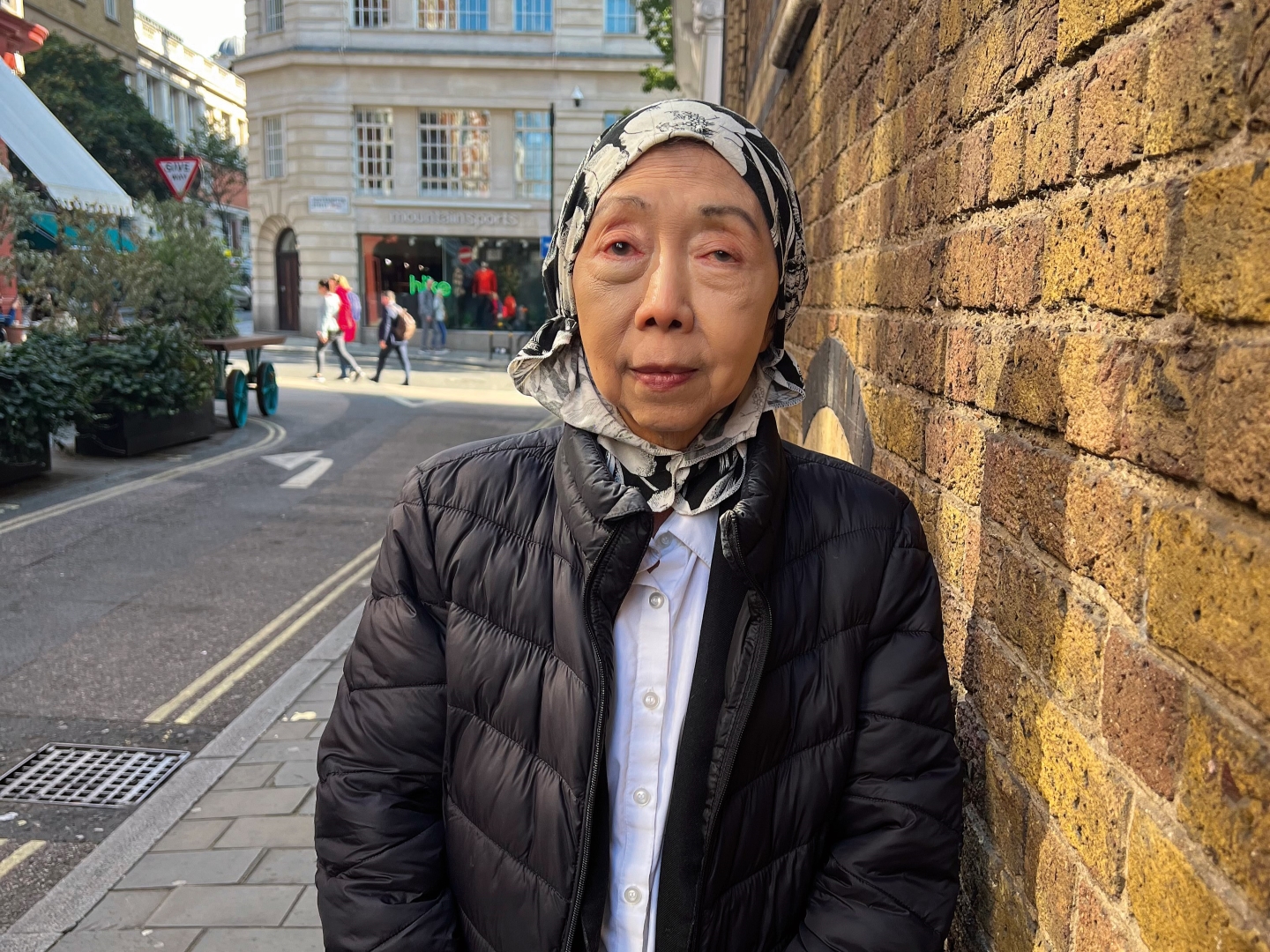

Ang: To be alive meant I had a duty to speak up on behalf of those who died... (Photo: Diana Khoo)

Poignant best describes the year 1948. It began with the assassination of Indian pacifist leader Mahatma Gandhi by an extremist. Midway through, our Tanahair was rocked by what would be the start of a guerrilla war between the military forces of the Federation of Malaya and communists that would become known as the Malayan Emergency or Darurat Tanah Melayu. Happening almost concurrently 8,000km away in the Middle East was what is now referred to as the Nakba.

Nakba, Arabic for “catastrophe”, is, by and large, a foreign word whose deep meaning and tragic significance are lost on most people. After all, the displacement and expulsion of Palestinians as a result of the Arab-Israeli War, which erupted on May 15, is still seen by many as “not our problem”. But for Dr Ang Swee Chai, born in October that same year, the event has become inextricably part of her — and her very reason to live.

The awakening

“How can I forget that I was born in the year of the Nakba? It is as old as I am and yet it is still ongoing,” says Ang, 76. This long-serving trauma and orthopaedic surgeon with Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) has devoted the last four decades to juggling her love and care for patients together with humanitarian work in what is arguably the most dangerous parts of the Middle East — the restive zones in Lebanon and Palestine.

Tiny and bird-like, she is just under five feet tall. We chatted over video call from her home in East London and arranged to meet near Covent Garden a few weeks later. To those curious about her headscarf, she wears it not for religious reasons, but because she lost most of her hair while battling breast cancer.

Born in Ayer Itam, Penang, Ang grew up in Singapore from the age of 10 months after her father secured a job there. “My parents, both journalists, met during WWII in Outram Road prison. They were resisting the Japanese occupation. Mum started out as a teacher but spent most of her time organising protests. She survived the war, despite being captured and tortured, as the Japanese could not believe a woman could be a community organiser. In fact, they thought she was the cook,” laughs Ang.

beirut_20101113.jpg

Inheriting her parents’ bravery and selflessness, Ang has been living in self-imposed exile in the UK since 1977, accompanying her husband, the late Francis Khoo, a lawyer who had to flee Singapore to avoid being indicted under its Internal Security Act. Khoo had been embroiled in a controversial trial, defending factory workers and student leader Tan Wah Piow charged with rioting — an industrial unrest incident that apparently infuriated Lee Kuan Yew.

“I had sensed he might be detained so I asked him to marry me. If he was arrested, I could visit him in prison and be his link to the outside world,” Ang recalls. The warrant for Khoo’s arrest came two weeks after the couple wed in January 1977. “He managed to escape but they came for me while I was performing an operation and promptly arrested me when I came out of the theatre. I was taken into custody and questioned and, upon my release, I joined him in the UK.”

Five years after they had settled into London life — “We had a small flat in the city centre” — she became aware of escalating conflict and tensions in the Middle East for the first time. “Prior to my life in England, I had no connections to anywhere or anything in the Middle East — by birth or culture. But night after night, television news bulletins featured Lebanon being blanket-bombed by Israeli planes. I read how 100,000 people were made homeless and 14,000 killed. This upset me terribly. First, because the wounds had been inflicted by Israel. Second, I am a Christian. And third, because I am a doctor. I concluded nobody cared so I prayed for understanding.”

It was in August 1982 that Ang’s colleague alerted her to an international SOS requesting the services of an orthopaedic surgeon to treat war victims in Beirut. “I felt God answered my prayers and knew what I had to do. After I made up my mind, for the first time that summer since war broke out, I felt at peace.”

beirut_20101174.jpg

Decades of devotion

Arriving in Cyprus soon after and en route to Lebanon, in the grip of civil war, Ang encountered her first Palestinian. “He spoke to me as I was stepping out of a lift, saying, ‘Doctor, you are going to Lebanon to help my people? Thank you very much, and welcome.’ I had asked if he was Lebanese but he said no, he was from Palestine. I then got scared, worried he might be a member of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) — as that was as much as I knew about Palestine then — and furtively looked to see if he was hiding a gun or grenade on his person. It turned out he was a lecturer in Arabic literature!” Deciding to chat and find out more over a meal, Ang began to realise she shared something in common with Palestinians: they were exiles like her.

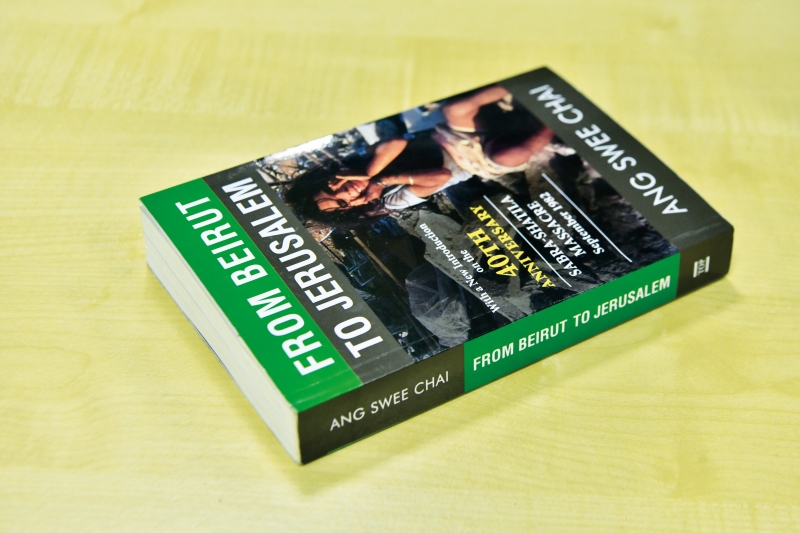

Once ensconced in West Beirut, Ang busied herself with work at Lahut Hospital, treating patients and performing surgery amid poorly equipped surroundings, with added chaos caused by intermittent air raids. What she did not know was that she would soon be witness to one of the worst massacres in living history, referred to simply as Sabra-Shatila. Thousands of civilian refugees, comprising Palestinians and Lebanese Shias, were killed by militia in their camps in a matter of two or three days.

“I knew for sure if I were Palestinian, I would have been slaughtered like everyone else, doctor or not,” she says, her voice cracking a little. “But the soldiers did not even bother to check my papers. After all, no one could mistake a Chinese for an Arab. But to be alive meant I had a duty to speak up on behalf of those who died, whose bodies were buried under rubble, and who could speak no more.”

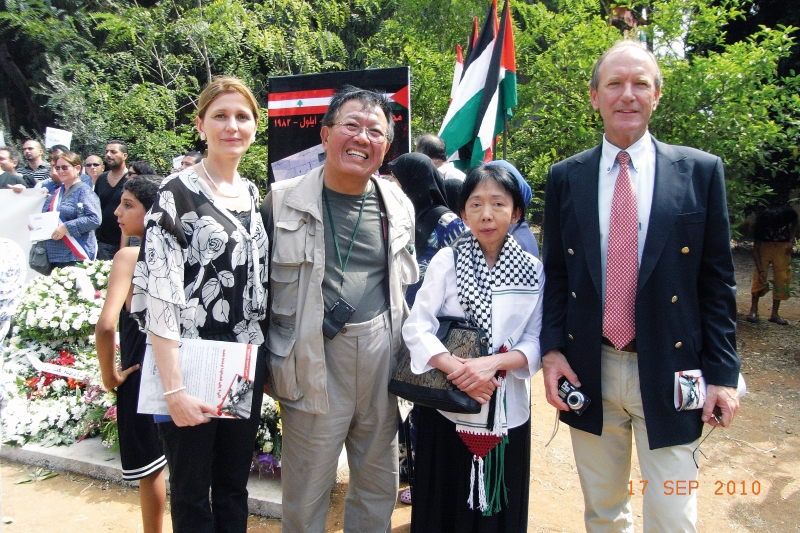

Beyond merely volunteering her services, Ang upped the ante upon her return to the UK by establishing Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP), together with Major Derek Cooper and his wife, Lady Pamela Cooper. A London-based non-governmental organisation that is into its 42nd year, the British charity, which enjoys special consultative status with the United Nations’ Economic and Social Council, focuses primarily on offering medical services in the West Bank, Gaza and Lebanon as well as meeting the humanitarian needs of the Palestinian people.

“I first met Pam and Derek in Beirut in 1982. Both are very special. Derek was, in fact, Pam’s second husband. Her first was killed in the 1946 terrorist attack which saw the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, then the British administrative headquarters for Mandatory Palestine, bombed, killing 91. Derek, also a soldier, was stationed in Palestine when the Nakba happened. It hurt him to see Palestinians clinging to the British tanks, trying to escape, to get out. He left the army soon after, joining Oxfam and other aid bodies. We met and got to talking, discussing what we could do since all the big organisations traditionally upped and left once funding was spent. This idea morphed into MAP (we insisted on including the name ‘Palestine’ for solidarity). And it has been wonderful, with many people rallying behind us.”

sam_6662.jpg

A heart to help

Apart from London, MAP maintains permanent offices in East Jerusalem, Ramallah, Gaza and Beirut, providing immediate and crucial medical aid in times of crisis, even when there are severe restrictions on access. This is made possible by its extensive networks, hard-built over decades, with hospitals, medical centres and community organisations. Specialist volunteer roles are also regularly advertised on their website although, due to the current emergency, all medical missions to Gaza and the West Bank have been cancelled until year end.

“A younger doctor friend of mine — a wonderful guy — recently called, saying he had to speak to me urgently,” Ang shares. “I was surprised when he told me he had signed on to go to Gaza, which is, by the way, 10 times more dangerous now than Lebanon was in 1982. I ran through a checklist with him. I asked: ‘Are you married? No. (Thank God). Engaged? No. (Thank God also). What if you get killed? Then so be it. What if you are wounded? I wouldn’t like it but would most likely be evacuated.’ I have to run through all these hard questions with anyone wishing to volunteer as it wouldn’t be fair to send a doctor with dependents, old or young.” She nevertheless acknowledges that the call is hard — and harder still for those sworn to the Hippocratic Oath — to ignore.

“I myself had wanted to return to Gaza last November and was trying to enter from Cairo. But then a dear friend met me and said, ‘Swee my darling, can we talk?’ He proceeded to run through his own checklist with me. He asked how long I could walk for. Less than an hour. Could I carry three weeks of food supply on my own plus a sleeping bag since we would have to bed down without a roof over our heads and amid ruin and rubble? I said I couldn’t although I really don’t eat a lot and don’t mind sleeping in the rough. Am I immuno-suppressed? Yes. It then dawned on me that as an elderly breast cancer survivor, going there and becoming a burden simply wasn’t on. But what I can still do is campaign, raise awareness and ask for help and support!”

beirut20102037.jpg

A friend in need

Ang is particularly effusive in her praise for Malaysians, saying the country was one of the first to support Palestine. “You have great people like [Tan Sri] Dr Jemilah Mahmood, founder of Mercy Malaysia. I’ve seen the work they do — quiet, good work and with no fanfare. When my rehab hospital was destroyed, it was Mercy that helped rebuild it. So I feel it is my duty to tell the Malaysian public about all the good their fellow countrymen do. It is truly something to be proud of and I wish everyone knew this. You Malaysians have been great, supporting Palestine for ages. Your people do so much while your legal team has been supporting the International Court of Justice, something which the British government would not do. The average Malaysian is also very generous in their contributions to MAP, especially considering the ringgit to pound exchange rate. It is Palestine’s blessing to have a friend like Malaysia.”

As a firsthand witness to countless atrocities and destruction, she reminds us how the present situation in Gaza is simply unimaginable. “Can you even comprehend how 2.3 million people are forced to live in an area of about 360 sq km? Over 100, sometimes 200, people have to share a single toilet. There are hundreds of Hepatitis A cases a day and now polio has been detected. Why? Because the UN cannot get in to vaccinate people. Even if a ceasefire was called, imagine how long it would take to begin rehabilitating the place and its people. The rest of Gaza is a firing zone. Over 17,000 children have been killed while Unicef believes another 20,000 are missing … buried under rubble, abducted … who knows?”

Reminiscing with sadness, Ang does not mince her summary of events. “The Palestinians had been in exile and struggle for over 70 years. Yet they remain completely humane, even under the most inhumane circumstances. The people of Gaza are as stubborn as they are resilient. Even under complete siege, they never forget who they are despite the Gaza of today being 100 times worse than Sabra-Shatila in 1982. The only positive difference now is that the world knows about events as they unfold. Back then, one only came to know about Sabra-Shatila long after it happened. Even I, who was working on the ground then, knew nothing of the mass murders until I was leaving the area. Now, the killings you see happen daily and in real time. The Palestinians have a voice but, alas, it is only to inform the world of their execution. The International Court of Justice calls it genocide — and I agree. It is. The whole world watches but what do we do? What can we do? That is the question I always ask. It sounds like nothing but if all of us do something, it can make a difference. Keeping quiet is not an option. Neither is despairing. And giving up? A complete no-no!”

beirut20102003.jpg

She goes on to say, “I’ve worked my way up through the UK’s race-based, hierarchical structure. So I understand that one cannot be silent in the face of injustice. We are supposed to be bold and fearless, bringing good news to the world. The UN cannot get any work done in Gaza now. Schools have been destroyed. Over 40,000 are dead, with another 10,000 believed to be under rubble. Even the Palestinian doctors and nurses have been taken prisoner which, by the way, is against the Geneva Convention. There are 36 hospitals in Gaza and all have been bombed, with only one remaining.

And this is the absolute worst thing! Hospitals are supposed to be the last resort, a refuge for the sick and weak.”

She speaks with such passion that one forgets she is 76 years old. “I still work full-time with the NHS and feel so tired sometimes … to the point of exhaustion,” sighs Ang. “But then I think of the Gazans and know I have no choice but to continue doing what I do.”

When asked whether there is any hope at all, she snaps and says, “The Palestinians? They never give up. They’ve endured 76 years of genocide. The West Bank continues to go through hell and they still call themselves People of the Land. You know, I met someone the other day with the surname ‘Midian’ and it floored me as I remember reading in the Bible how Moses’ father-in-law was a priest of Midian. Just look at how these families and their names have endured since Abrahamic times.”

Although Ang has no children (“I have five cats though,” she smiles), she remains close to her siblings. Her brother, also a doctor, lives in Canada, and she has two sisters, in Kuala Lumpur and in Singapore. “We are all separated as well but cannot even begin to compare our situation to the Gazans. We are free to fly here and there to see each other when we please. I was only very hurt when, in exile, I could not attend my parents’ funerals. But, as I remind myself daily, millions have it far worse. Now, I am too old and weak to go to Gaza but I still have a voice.” And by God, does she use it.

To donate to Medical Aid for Palestinians, visit map.org.uk.

This article first appeared on Oct 14, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.