Charles Spencer with his sister Diana and nanny Mary Clarke, before heading for Maidwell Hall as a new boy (Photo: John Spencer)

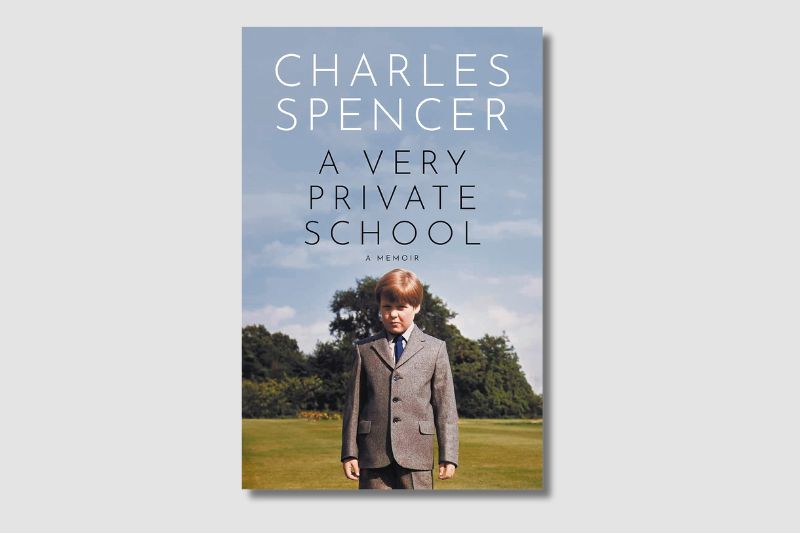

The abandonment he felt when sent to an elite boarding school at eight, and anger over the virulent effects of the physical, sexual and psychological abuse he and fellow students suffered behind its imposing façade are the basis of Charles Spencer’s memoir, A Very Private School.

Things happened there that he knew were wrong, but the whys were beyond his young mind. Worse still, there was no one he could turn to because, at Maidwell Hall, tucked away in rural Northamptonshire, students were cut off from those they knew and loved, and “at the mercy of some really bad people”.

As a child of a bitter divorce — Spencer’s mother Frances Shand Kydd left his father for another man when he was two — he was even more affected by the misery of being alone and homesick in his early years as a boarder.

Showing a historian’s care for detail and journalistic flair, his accounts of casual cruelty inflicted on schoolboys by toxic teachers and staff at Maidwell from 1972 to 1977 build up with a menace that must have been palpable when the young ’uns were summoned to the headmaster’s room, where he waited with two canes, the Flick and the Swish.

John ‘Alec’ Porch, nicknamed “Jack” by the pupils, gave it to them gleefully as they braced themselves over a pouf, underpants pulled down and buttocks exposed. “He would cane five strokes parallel, drawing blood, and then the sixth stroke across the five.” Spencer, who will be 60 in May, writes that a friend his age still has the scars from 1977.

In the five years that he spent thinking about and working on his book, he reunited with and had chance encounters with many contemporaries. He asked what they remembered most about the place, promising not to identify them, even though some said that would be fine.

James Temple, who was fondled and whacked on Jack’s pouf, said Maidwell was ruled by fear, the cloud that hung over every class, and the staff were all complicit.

Perry Pelham, for whom the school was all about beating and pain, said: “There were actually very few rules — you only really knew you were in trouble again when preparing for the next beating” — for God knows what, cohorts wondered too.

charles_spencers_memoir_a_very_private_school.jpg

Anthony Stapley, a non-swimmer forced to take the plunge and almost drowned, felt their experiences had made them “tough, resilient and hardy … but also left them wary, untrusting and emotionally retarded/unstable”.

The most heart-rending response he got was from an old boy who, upon learning about the book, confessed to his wife of 40 years about the despicable things done to him by Jack and his allies. The pair then hugged and cried for an hour.

Worse than the pain inflicted on bare flesh that bore into their pores were the psychological torments: Pupils were shamed for being overweight or genetically different, belittled for poor marks, ridiculed when they showed their emotions and then threatened with retribution if they squealed. Callous Jack and his staff, willing henchmen who closed more than one eye, had the power to hurt and wielded it regularly. Emboldened by what they saw, various seniors in the school became bullies too.

The worst of what happened at Maidwell would be the sexual assaults on innocent prey, acts shrouded by silence and secrecy. On nude swimming jaunts with hand-picked students, a paedophilic master insisted they could only get into the water via “the human slide”.

Wealth and priviledge did not shield the 9th Earl Spencer, a godson of the late Queen Elizabeth II, from Jack, who charmed parents with amusing term reports on what their children were up to, and was all smiles during their rare visits.

The boys witnessed a teacher being aroused as he caned some boys. At 11, Spencer was among the victims of a young assistant matron who slipped the vulnerable pupils sweets at night, then returned to them under the covers.

“I thought it was exciting to have a female interested in me because it was a place that didn’t have any form of maternal warmth or kindness. She was grooming me — she gave me grapes and biscuits and came back for sexual things. I knew it was wrong but I couldn’t get my head around it,” he says in interviews about that dark episode of touching and being touched, which he blames for “awaking in me basic desires that had no place in one so young”.

About two decades ago, as child sex abuse by Catholic priests came to light, scandals surrounding English private schools also surfaced. In 2015, Spencer wrote to a London lawyer involved in these prosecutions about attending “a horrific place overseen by a terrifying and sadistic headmaster”, to seek advice on possibly taking legal action. That came to nought, as did his plan to approach Jack and ask about things that still haunt him, and his boyhood promise to himself to trace down a teacher and exact revenge.

Psychotherapists he saw over decades told him that trauma at a young age often leads to memories being expunged, or it can go the other way. Having met many survivors who “left Maidwell with demons sewn into the seams of our souls”, he was convinced that he had to do the right thing. “Someone has to tell our story”, his friends said. He did, even though writing the book brought back recurring nightmares and the crushing migraines he suffered years ago.

A chapter on a day in the life of Maidwell’s 75 students — the student population when Spencer was there — reveals a rigid routine that kept them busy and submissive. To make them go daily, Granny Ford, the matron in charge of domestic staff, dished out pills that the boys swallowed without water to save on washing up. But there were also inventive fun, games, trips out and colourful accounts of mealtimes, which give readers a peep into the routine at such exclusive institutions.

Photos of ancestors; Althorp, the stately estate Spencer inherited from his father; him riding his pony Teddy Tar or playing with his dog Gitsie; and shots with his mother and sisters Sarah, Jane and Diana, the late Princess of Wales, underline how he must have missed the comforts of home and provide a stark contrast to life at Maidwell.

Spencer has a nice turn of phrase and pieces together his recollections in crisp reported speech that reflects his decades in journalism. There is no mush or maudlin dawdling, just character sketches and clear details as near to the truth as he can remember, often drawing from school reports, his diaries and letters home.

He shares memories of kind teachers who made life more bearable at horrific Maidwell and happy incidents and comradeship with boys his age, and includes comments by those who enjoyed their time there.

Isaac Ewer said that as he was good at sport, reasonably good-looking and fairly academic, things were relatively easy for him. Even so, this ex-head boy admitted there were things about the school that were “deeply weird and strange … [It was] like a prison camp”.

Among the weird things were having the students address all female staff members as “Please”, and ragging: After tea every evening, the boys had to pick someone to fight them aggressively.

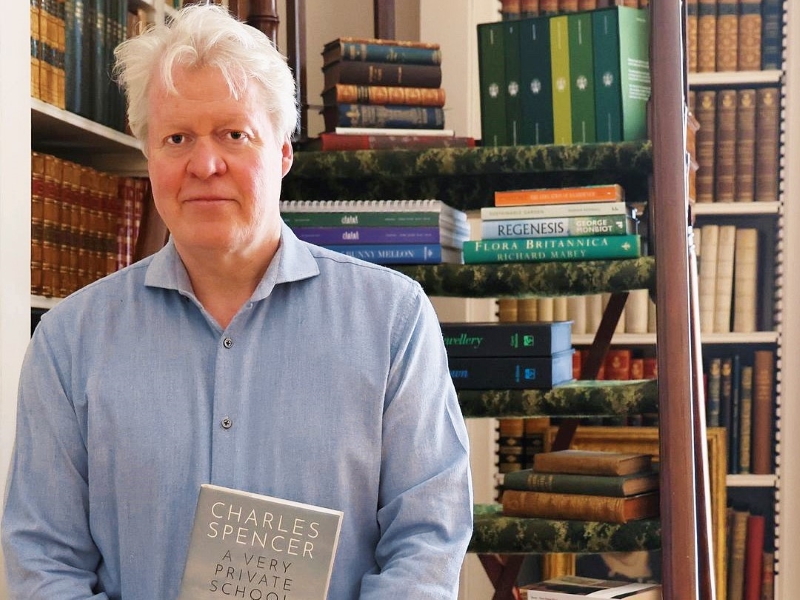

Spencer, a historian with seven books — among them Althorp: The Story of an English House; Bleinheim: Battle for Europe; and The White Ship: Conquest, Anarchy and the Wrecking of Henry I’s Dream — states that he is not seeking sympathy with A Very Private School. Instead, he wants to try and make sense of why the adults entrusted with the care of those at Maidwell let them down so terribly.

charles_spencer.jpg

Retracing his footsteps has enabled him to reclaim his childhood, he believes. In response to those who ask why he did not speak out earlier, Spencer points to the English boarding school system, which affords a cover for heinous acts perpetrated in the shadows.

With no emails or mobile phones in the 1970s, students were literally cut off from the outside world and loved ones, except for the weekly letter home, read by a staff member first.

In a breakfast TV show, he said it was not normal for children from his background to confide in their parents. “We didn’t talk about things; it was too awkward. A lot of parents didn’t know.” Some might, but thought sending their children to a brutal place would toughen them up.

No one whom Spencer spoke to told their parents about what was going on, partly because “we were so young: We had no context to our lives; we didn’t know how bad it was”.

He recalls how a day boy was beaten so badly that he had to be soaked in the bath to get his underpants off. “He went home and his mother never said anything.”

Sons of the upper class were enrolled at prestigious schools not designed to meet the child’s educational or emotional needs, he writes. Rather than serving the individual, the system was “nurtured in the strong rays of the British Empire, to populate and replenish the ranks of those who administered, controlled and expanded that global mission”.

Parents know best, children thought and so endured being packed off to boarding school. While some parents chose to ignore evidence of ill treatment, others were glad to have others care for their kids, leaving them time for themselves.

Twice-divorced Spencer, a father of seven, said he lacked understanding of intimacy because he was sent away so young. He does not believe in plucking young children from the home and placing them in the hands of strangers. He thinks Maidwell snuffed out the happy effervescence that had his mum calling him “Buzz”, making him constantly watchful and guarded, to protect himself against bullies.

Purchase a copy of 'A Very Private School' at RM147.60 from Kinokuniya here.

This article first appeared on Apr 8, 2024 in The Edge Malaysia.