Shaheera Shahab and her father Datuk Syed Mustaffa Shahabudin (Photo: Suhaimi Yusuf/The Edge)

Although it was Shaheera Shahab with whom I made arrangements to meet, it turned out to be her father Datuk Syed Mustaffa Shahabudin who greeted me at Pampas in Old Malaya, the row of once crumbling shophouses converted into high-end eateries that he had a hand in developing. Nursing a cigarette and a cappuccino, Mustaffa is pure old-school class right from the crisply ironed white shirt to the shiny brogues and jacket arranged just so on the back of his chair. He is also a good 15 minutes early, and we indulge in some chit-chat while waiting for his daughter to arrive.

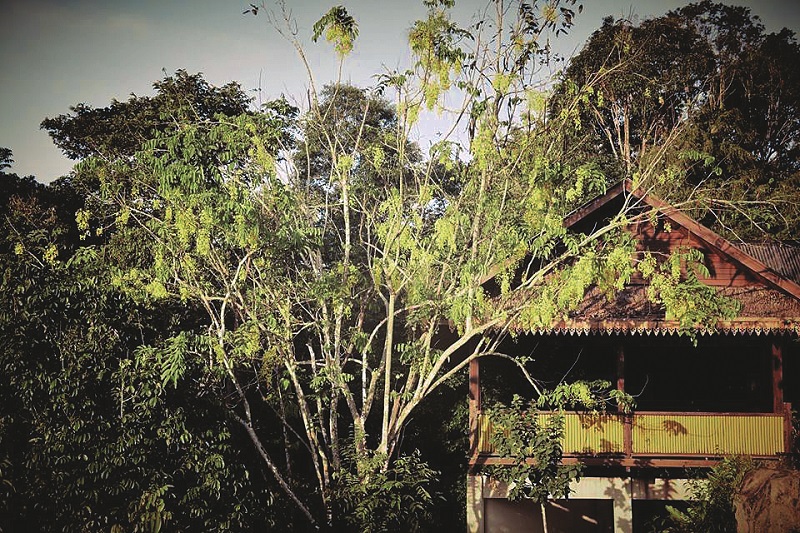

Mustaffa is a successful businessman whose diverse interests over the past 35 years have included publishing, real estate, hospitality, investment and IT. He is best known for founding Tanarimba, his flagship eco-living project in Janda Baik, Pahang, located amid 7,299 acres of lush tropical rainforest at 1,500 ft to 4,500 ft above sea level. Mustaffa has set aside just one-fifth of Tanarimba for low-density development, with the remaining land maintained as a forest reserve.

“I’m a bit of a conservationist, both architectural and natural,” he muses. “I called this development Old Malaya because I was born and raised during the Malayan times. I was born in Alor Setar but went to boarding school in Penang. Back then, there was no Malay, Chinese or Indian, or any sort of racial division. I want to go back to those days, and I see that, now, people who come here are also of all races.”

Shaheera arrives, and more coffee is ordered. “You know, I admired this place from afar for 12 years, as we couldn’t find the owner for a long time,” he adds, glancing outside the window to the afternoon traffic. “It was very dilapidated, that’s why it cost us a bomb to refurbish. But I was really in love with this place. The owner wanted to know what we were going to do with it, and when I said fine dining, they were happy to let us lease it. I even wanted to take over the stretch of old houses on the other side of the road, but the owners sold it and they were all demolished — that was devastating.”

oldmalaya3.jpg

Mustaffa is old friends with Kana Theva, veteran restaurateur and founder of the Pampas Group, and roped him in to open a branch of the steakhouse at Old Malaya. Shaheera had by this time completed her university education and was licking her wounds after an unsuccessful business venture. But her father knew how to persuade his strong-willed, independent daughter to work with him.

“It was by saying I wouldn’t work directly with him,” she laughs. “At that point, Pampas was already open and Old Malaya was operational. Dad told me to work directly under Mr Kana, and not him. So, that’s how we started four years ago. Two years later, we started work on Mari House, but now, we are focusing on dad’s two main projects, which are in Janda Baik — Tanarimba and Kebun Rimba, our private estate.”

A private garden that Mustaffa has personally tended to for the last 30 years, Kebun Rimba was originally a rubber plantation. He cleared the trees and worked with the Forestry Department to reintroduce native plants and other flora to the garden, merging it with the neighbouring forest reserve. “The wildlife has also returned,” he says proudly. “The theme is Rainforest Discovery Centre, but we call it the jewel of the rainforest. Tanarimba is a core business, and Kebun Rimba is Shaheera’s — I’ve passed it to her to manage. And that project is very valuable because, if another pandemic happens, we are all going straight there,” Mustaffa quips.

When Shaheera initially came on board to work with her father, his intention was to provide her with real-life experiences that her university education could not. “I worked in marketing, managed the restaurant, learnt how the supply chain worked, and I also worked the floor,” she shares. “I also worked with the other tenants to build effective restaurant eco-systems. Two years ago, dad asked whether I wanted to open another eatery, and that’s how Mari House was created. We did everything from overseeing the design and construction to serving patrons when it opened. I had a great support system through dad and Mr Kana, which I am so thankful for.”

kebun_rimba.jpg

With so much time spent together professionally, do they bring work home to the dinner table? “Oh yes,” Shaheera says, grinning. “I don’t think we’ve ever had a meal where we didn’t talk shop. He says he has let things go for me to manage, but he has a hand in everything we do — which isn’t altogether bad, as the team and I really appreciate the guidance. But we don’t prolong any arguments — fights are over quickly, because there’s soon something new that we need to talk about. My mum and husband often play mediator when we argue because dad and I are so alike — we are both equally opinionated.”

“When you are in business with family and you quarrel, it’s because of the concern over the business, not because of egos,” Mustaffa puts in. “At the end of the day, it’s not about money but passion. You must be passionate about anything you do. If money was the objective with Kebun Rimba, I would never cut down those rubber trees! You don’t earn any money from replanting forests. But the result is a beautiful garden that I love, and that so many people also love.”

Shaheera nods in agreement. “I enjoy working for dad because of the balance — we work for money, but we work hard to earn it. And there’s a sense of ownership he’s instilled in us. We still work the floor, clean tables and serve the food, while dad would water the plants around here, look in the back lane and check that it’s been cleaned.”

The Movement Control Order (MCO) was a hard time for restaurants, even though they were able to open under strict government guidelines when the lockdown moved to its next phase. Aside from Pampas and Mari, other eateries in Old Malaya are Luce Osteria, Manja and Pier 12, all of which have survived. “Across the board, many restaurants closed. But we are very conservative, with minimal borrowing, which was why we could survive. Right after it was okay to open, we did, of course adhering to all the rules and SOPs. Pampas is doing well and, from what I hear, the others are too,” Mustaffa comments.

pampas_steakhouse.jpg

There are currently two empty lots in Old Malaya, which Shaheera is actively searching to fill as KLites get increasingly less skittish about eating out. Although nothing has been signed yet, Mustaffa remains in serious talks with the owner of Bukit Tinggi icon BBQ Chan.

“One of my biggest learnings, post-MCO, is the value of money,” Shaheera says. “We were married barely two weeks before the lockdown, and it was a good reminder of how fortunate we are, and the value of even one ringgit. I didn’t draw a salary, but I was lucky enough to have my father — so many people don’t have that. We made sure we took care of our staff, which is important because the place does well, thanks to them. I also learnt a lot about the benefits of a healthy, self-sustaining eco-system for the business, and how to maintain it.”

So impactful was this learning that Shaheera and her father are now working out how to include more agricultural activity in Janda Baik. They have the land, after all, and the perfect weather too. “We have a plan,” Mustaffa says, leaning forward. “Kebun Rimba will be completed — it’s about 80% there already, and we hope to open to the public at the end of the year. Then, the agriculture. The restaurants … we have some really strong outlets here in Old Malaya. We are looking at some other heritage areas to see whether there’s anything we can do. Two years ago, we took over a small, boutique hotel in Phnom Penh with some partners, and now we are looking to expand in other heritage areas such as Luang Prabang and Siem Reap, but all small boutique hotels.”

Mustaffa has 11 siblings; so, many of Shaheera’s cousins are involved in the business. While there are advantages to keeping things in the family, it does mean that everyone is obliged to report to their uncle quite regularly. “He’s quite old school, so we’ve all learnt to be agile enough to adapt to his guidance,” Shaheera says affectionately. “He may not approve of everything I say or do, but I cherish his advice very much. And I think I am very lucky to work with someone like him every day.”

This article first appeared on Sept 7, 2020 in The Edge Malaysia.