Loh joined WCC as executive director in July 1997 (Photo: Soophye)

Women’s Centre for Change (WCC) executive director Loh Cheng Kooi can see the wood for the trees. In fact, she “saw beyond the trees” when she first stepped into a wedge-shaped, three-storey building at 241, Jalan Burma in George Town around 2010.

“It had been abandoned for years and was all dilapidated. But its one floor was equivalent to the space of our [then] Jones Road office. I told our general committe, ‘By hook or by crook, we are going to buy up this building.”

She did, for RM1.5 million, and spent another million on renovations — money accumulated from huge fundraising efforts — before WCC moved into its present home a decade ago. “What you see today is completely new. It was just a shell before we did the wiring, tiling and the space outside the building. It was like a jungle.”

Determination drives Loh, who joined WCC as executive director in July 1997. The organisation, registered in 1985 as the Women’s Crisis Centre, helps women and children who are abused, raped or sexually assaulted. Victims get face-to-face, telephone and email counselling and legal advice for free and all cases are confidential.

Loh is looking to “change the mindset of business people” who take part in corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental, social and governance projects with NGOs (non-govermental organisations), such as WCC.

“They should look at staff of non-profit organisations as professionals. It is wrong to think NGOs are run by volunteers. We love what we’re doing and would like companies to fund our work of helping people. Companies need to recognise what NGOs do and allocate their CSR funds to support our staff and the activities we undertake.”

pgo.jpg

When corporates approach her because they are interested in what WCC does, she will draw up a proposal for running children’s programmes, developing resources and conducting training. “But when I ask if they will pay for my trainers, they won’t fork out money because they do not expect an NGO to put up a proposal for RM20,000. They expect one for RM5,000.

“Bosses have to understand what helping an NGO is about. Many don’t. NGO business is helping the underserved communities. Company business is to make profit. Corporates doing CSR can support NGOs so a group of dedicated people who decided their career is to help others can do that.

“I’m the main fundraiser for WCC and our annual budget has grown to over RM1 million, to sustain 16 professional staff — social workers, outreach officers, legal officers and managers — and our work of service, outreach and advocacy. It’s hard work raising such a huge sum every year but I am very determined in everything I do.

“We developed all our resources and continuously update them so we can use them to train more people on preventing violence against women and children. I send my staff for training too. I’m running this like you would any agency or company. Companies pay their staff good salaries; I want to pay mine a decent salary too.

“Our business is really about working for people, whether we’re lobbying for legal reforms affecting women and children; going to schools to teach about child sexual abuse prevention; or helping a kid who has been molested. We are paid, full-time staff dedicated to this work. As a non-profit, part of the money we make is used to pay professionals who can run the work we do well. This is not less expected of a company that is making profit — there’s no difference.”

European foundations and agencies used to fund NGOs but such aid dried up after 2000, when Malaysia attained developed-nation status: Local companies are expected to have the means to help their own people. There is scant help from the federal government, Loh says, even though the domestic violence cases WCC handles fall under the welfare department.

The Penang state government gives WCC an annual grant to manage the Pusat Perkhidmatan Wanita (PPW) in Seberang Perai. This women’s service centre was set up at the behest of the Pakatan Rakyat coalition when it assumed power in Penang in 2008, to replicate what the organisation does on the island.

community_outreach.jpg

There is no doubt Loh chooses to work with non-profits. “At certain points, I could have gone to multinational corporations but for some good reasons, I’m still here. Likely because I enjoy working directly with people. Prior to WCC, I used to be with a non-profit in Hong Kong for which I travelled throughout Asia to assist women’s labour groups. I took the bus and lived with friends around different countries.”

The Penangite was also involved with the Women’s Aid Organisation when it first started. Subsequently, this nutrition science graduate pursued her master’s in women and development in Holland.

Asked to take charge of WCC, she gave herself three years because foreign grants used to be for that duration. “I always told myself I would leave after three years. But the beauty of working here is, every day you come in, there’s something different that keeps me motivated. What next? How to help things?”

Loh has been asking these questions for 25 years at the organisation that started purely on a voluntary basis. It is how non-profits begin, she continues — small, by a group of people with big hearts looking at a need and saying, “Let’s do something”.

As WCC grew, it began attracting volunteers who started going to flats to give talks. Housewives came in and as word spread, lecturers and lawyers offered free legal advice. The group worked with schools to run programmes, such as Say No to Sexual Violence. In the 1990s, it was already talking about child sexual abuse, a taboo subject then. “Now people have acknowledged it is an issue.”

42948907_2126836527348895_5338862743720034304_n.jpg

In 2002, WCC decided a name change was in order to reflect its wider focus on women’s empowerment through education and advocacy. But it wanted to retain its already-familiar acronym, thus the Women’s Centre for Change. By then, it was helping children aged 10 to 12 years understand the difference between good and bad touch with its OK Tak OK video and cartoon booklets; giving public talks on gender violence and discrimination; and working with the community to raise awareness of and prevent sexual abuse in society. It also joined the Joint Action Group for Gender Equality, a coalition of 14 women’s rights organisations in Malaysia, to lobby for legal reforms and better policy for women and children, like a sexual harassment law.

WCC’s core work covers three areas: service, outreach and advocacy. Service, its main arm, involves counselling and support for women and children experiencing crisis, especially domestic violence and sexual assault cases. It offers temporary shelter to those in need of protection, gives legal advice in family matters like divorce, as well as victim support — a social worker accompanies the victim to the police station, hospital, Social Welfare Department and the court, if the case ends up there.

The legal support WCC offers is what makes its work so special for clients, Loh says. “We get so many thank yous. People are grateful because we explain the court process to them simply and follow them through the trials. In a year, pre-Covid, we would do about 70 cases.”

The pandemic fundamentally changed how the team worked as they had to switch from face-to-face to mainly phone and online counselling. With a special grant from Yayasan Hasanah, WCC bought handphones for the staff and increased its hotline from one to four lines. “Phone counselling became big for us and we realised calls were coming in nationwide, not just from Penang.

“When our office reopened, clients quickly dropped by — proof that face-to-face counselling is important for those in crisis. Many women cannot do online counselling at home because of the lack of privacy — they are basically from low-income families and there is no space. It is really difficult to talk about mental issues over the phone.”

WCC also lends hospitals support. Since 2009, its people have been going to the One Stop Crisis Centre (OSCC) at the Penang Hosptial to attend to victims of sexual crimes or domestic violence, after obtaining their consent. In 2011, this service was extended to Hospital Seberang Jaya on the mainland through the PPW. Currently, it collaborates with all six main and district hospitals in the state.

Domestic violence or sexual assault cases are handled in privacy at the OSCC, tucked in the emergency department of all government hospitals across the country.

wcc_value_shop.jpg

Last year, domestic violence and child sexual abuse made up 58% of the cases WCC handled, Loh says. The majority of sexual assault victims are children. “We are active on prevention because we believe if we don’t prevent this problem, we will have many girls, especially, who are not going to have normal family function later — get married and have healthy relationships.” Another hope is they will not get into a domestic-violence relationship with their partners.

“Any child who has been sexually abused is psychologically scarred for life. But when you help her to heal and recover, you make a difference: The child can go back to as normal a life as possible. Oprah [Winfrey] was raped as a child; see how successful she is today.

“Sometimes that gives us the determination to do this kind of work. When the issue is not settled at the point it happens, when a parent did not believe you or you have kept it a secret, later in life, it impacts you in a far worse manner. We’ve had adults who phone us 10 years after the incident, saying, ‘I need to talk to you’.”

Domestic violence, on the other hand, is extremely complicated because it usually happens within the family. WCC has had cases of women who, after being bashed left and right, suddenly withdraw their charge — after they are all prepared to go to court.

“When you want to help women, you go with no expectations,” Loh emphasises. “You can’t have a condition — ‘You must go to court’ — because the decision goes back to the client, who often has limited circumstances. She may be dependent on her husband; she may have children; the husband begs for forgiveness; she thinks she still loves him. A woman could leave her home five, six times before she is really determined to move out.

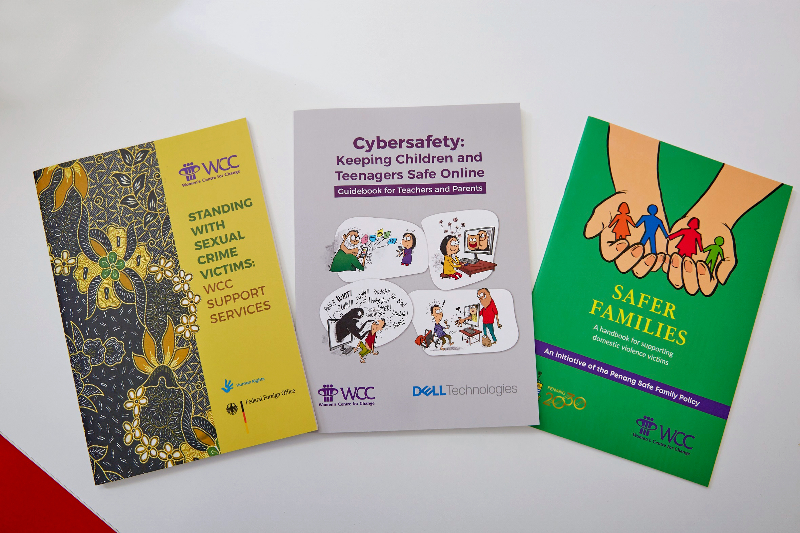

wcc_books2.jpg

“Our work is empowerment, not welfare. We are a women’s and child rights office. Meaning, we respect the woman’s decision even though we ourselves might choose a different option because we have the resources. She does not. Every person has the right to choose and that right is very important, child or adult.”

In instances when mothers and their children need to be housed in temporary shelters — to give them peace of mind while they get counselling — husbands do show up at the WCC office. Most of the time they are very nice because they want their wives back, Loh notes. “They tell us a different story but we have to be fair and listen. Half the time, the women go back. We cannot judge them, even if the case is old.”

Does it affect her to frequently meet people beaten or abused? “Yes and no. We do service and outreach, and advocate for change — giving feedback on and having discussions with the authorities about a problem. We also work with the government and the agency that handle these cases to change the laws. You cannot be caught up with emotions.”

Of course, some cases get to her, like that of two women raped by their stepfather — their offspring are now 20 years old. “How not to

be depressed when you listen to this? But you have to think about why they never reported. Incest is a very serious issue and nobody wants to talk about it. And this is in the city. What about in the rural areas, where the mother has limited say, where the husband is deemed head of the household?”

Counselling empowers a woman with the knowledge of what is right and what is wrong, and to have the mental strength to say that when something is not right, she, as an adult, can do something about it. “This empowerment is very important because she herself has to make that decision. When we counsel a woman, we help her make informed choices.”

At the end of the day, what matters could just be “we’ve helped her move that five steps forward. To let her know what her husband did was wrong and to ask, ‘Do I want this for my children?’ Sometimes it’s the kids who tell their mummy to please leave.”

Thus, educating the young is crucial, and WCC does that through school outreach activities focused on personal safety and sexual violence, using its own books, videos and manuals. Finding My Voice and Boyz are programmes for girls and boys, respectively. Respek and Cybersafety are for teenagers, while Bijak itu Selamat (Be Smart, Be Safe), available in three languages, offers training for educators. This package comprises a manual entitled Teaching Children to Be Safe, a pen drive with short video clips, and two cartoon booklets, Nina dan Rahsianya and Saya dan Suara Kecil Saya.

With cybersafety under threat in homes today, WCC highlights online violence by looking at trust issues and how we share information with friends, chat apps and sexting, as well as cyberstalking and bullying. It also teaches children how to stay safe and where to get help when threatened.

Despite all its resources and efforts, Loh knows as an NGO, WCC can only do so much. For that reason, states and businesses need to first support women’s centres and work with them. Given a reasonable budget, they can then recruit personnel who are willing to make a career of serving the underserved.

“There are many people out there who want to do this type of work but we need to pay them decently so they will be willing to stay and do something they love. I mean, if you love the work you do, what more can you ask even though your pay is slightly lower?”

This article first appeared on Jul 11, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.