These books are packed with stories of how unique ideas were born and translated into fabric as well as who influenced what

Snobs may scoff and say you either have style or you don’t; the fashion experts know better. They assure us that, like most things, dressing to suit one’s personal style can be learnt. What better way to do so than through books that follow trends and pick out what’s cool or hot, and are packed with stories of how unique ideas were born and translated into fabric as well as who influenced what.

Fashion is a barometer of the times, with attentive designers, artisans and icons pulling threads from what they see and know and weaving them into clothes that reflect things going on around them, be it rebellion, celebration or innovation. They embellish their creations with colour and verve and hold up pieces that people relate to and want to wear. After all, as Marc Jacobs said, “Clothes are nothing until someone lives in them”.

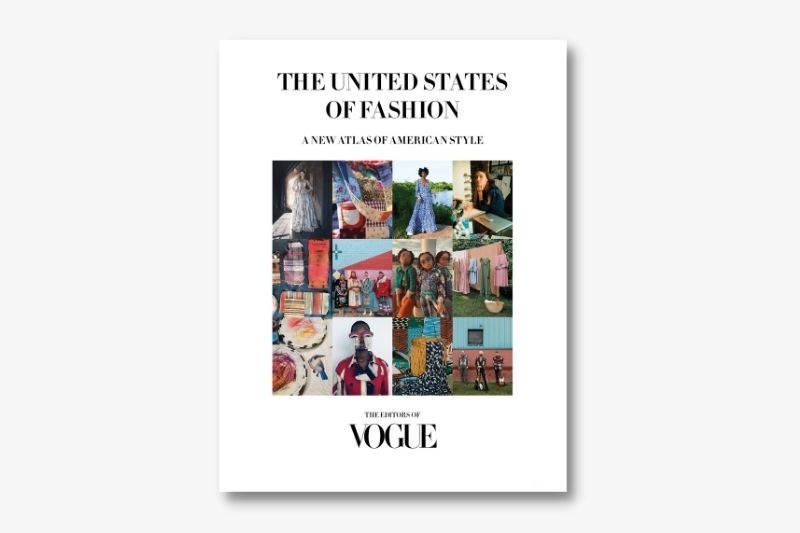

The United States of Fashion: A New Atlas of American Style

Cancelled shows and empty runways in the fashion capitals this past year have prompted designers to look for inspiration in their own backyards, literally. An affirming outcome of the pandemic is a chorus of fresh voices talking about comfort clothes, sustainable materials, caring for the Earth, pivoting to stay relevant and reaching customers digitally.

Vogue America’s The United States of Fashion captures the narratives of new designers across the country who, through pictures and words, share how they interpret and identify with fashion today. The book is the result of a project under the same name launched by the magazine in February, to bring to the fore creatives and crafts flourishing locally.

Written by Vogue editors who travelled from coast to coast, it maps out innovations and ventures that define American fashion — which has evolved under trying circumstances, with consumers wanting more conscious clothing and comfort but spending less, as the coronavirus changes the way people live, work, shop and play.

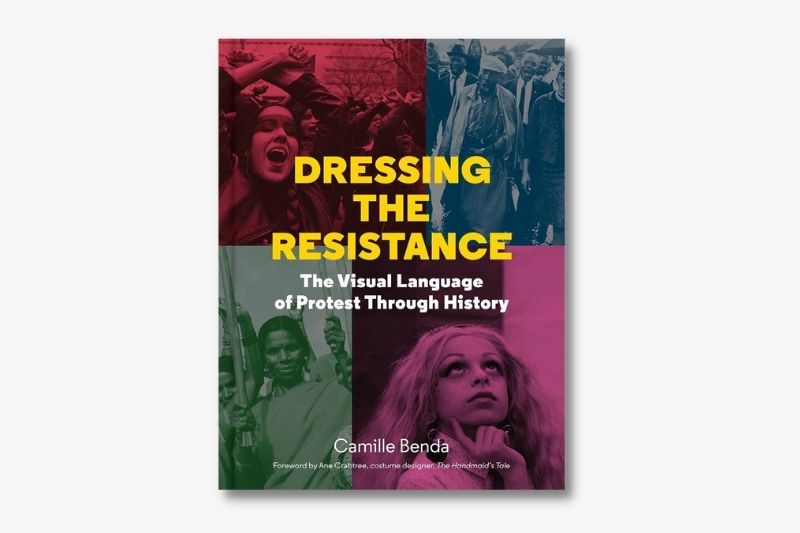

Dressing the Resistance by Camille Benda

Zeroing in on what Mahatma Gandhi wore over the years, the Gandhi Book Centre notes that he swapped coats, pants and hats for a lungi (a traditional garment worn around the waist), then a dhoti (long loincloth wrapped around the hips and thighs, with one end brought up between the legs and tucked into the waistband) before changing to a khadi wrap, a hand-spun fabric made from cotton, which came to symbolise India’s struggle for independence.

Clothes may not make the man but they certainly can ignite activism and spur social change, costume designer and dress historian Benda writes in Dressing the Resistance (available from Oct 19). American suffragettes marching to the beat of “Deeds Not Words” wore dresses made from old newspapers printed with voting slogans. Indian farmers wore their wives’ saris to stage sit-ins on railroad tracks. Safety pins dangling from earlobes or fixed on ragged jackets were viewed as “a cultural expression of angst, emotion, and volume”, Billboard magazine said of the punk movement.

From rebellions in Roman times to women crying #MeToo today, clothing, textiles and costumes figure as tools to agitate for change. Protest fashion — from uniforms and tees to headbands and hats — galvanises support and communicates discontent. A journal article titled “Dressing for Freedom” described Rosa Parks as “impeccably dressed in tailored clothing” when she was arrested in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, for violating a law on segregated seating on public buses. Her quiet style and dignified bearing, emphasised by protest organisers, helped fan the fight for social equality.

Nevertheless, She Wore It: 50 Iconic Fashion Moments by Ann Shen

Women who dare, wear. In Nevertheless, She Wore It, writer-cum-illustrator Ann Shen leads us back to specific moments in years past when people ignored social norms and chose clothes they fancied, and lifestyles to suit, paving the way for radical change.

After World War I, American women joined the workforce in droves, were given the right to vote and had easier access to mobility, thanks to automobiles. These factors are said to have shaped the flapper dress — straight, loose outfits with a waistline at the hips and a hem that falls between calf and knee, leaving the arms bare. Young flappers flaunted their “outrageous and immoral” lifestyles in these dresses as they pushed for economic, political and sexual freedom.

The bikini introduced by French designer Louis Réard in 1946, the first war-free summer in years, was named after the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean where the US tested the impact of atomic bombs on naval vessels. Its liberating effect on women’s swimwear rippled across the world. To quote French fashion historian Olivier Saillard, “the power of women, and not the power of fashion” was the reason those scandalous bits of cloth caught on.

Long before #BlackLivesMatter, the voluminous Afro symbolised rebellion, pride and empowerment during the Black is Beautiful movement of the mid-1960s. In the ensuing decades, individuals made personal statements through fashion, either loudly — Madonna flaunted her sexuality on stage in her Cone Bra corset created by Jean Paul Gaultier — or quietly — the late US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wore elaborate jabots over her black robes that said style and what she thought of certain people in power. Between her “dissenting collar” and “majority opinion” necklace, she was seen, and surely heard.

Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births by Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick

This book had its seed in the 1956 [Einar] Egnell SMB Breast Pump made by the Swedish engineer that Millar Fisher, a curatorial assistant at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art in 2015, tried to acquire for its collection. Nothing came of that but she, together with design historian Winick, began looking at the link between reproduction and design. That led to the birth of Designing Motherhood, as well as a similarly titled exhibition at Mütter Museum in Philadelphia, the US, which opened in May and runs until next May.

The authors examine more than 80 designed objects described as “iconic, conceptual, archaic, titillating, emotionally charged, or just plain strange”, among them home pregnancy test kits, pregnancy pillows, the tie-waist skirt women wore in the 1950s to hide baby bumps, gender-reveal cakes, baby carriers and baby-wearing in traditional cultures, wooden baby boxes the Finnish government gave expectant mothers, lactation pods and, naturally, breast pumps.

History and story, interspersed with photographs, drawings and historical advertisements, emphasise how design and objects shaped women’s reproductive experiences and the relationship between people and babies over the last century.

Extraordinary Voyages: Louis Vuitton by Francisca Mattéoli

Luxury travel and fashionable gear go hand in glove and Louis Vuitton combines both with panache. The brand itself had a footing in travel, when its eponymous founder (1821 to 1892) left his hamlet in Jura, France, at 13 and walked to Paris. The 400km journey took two years and he did odd jobs to pay his way.

Extraordinary Voyages is far removed from Louis Vuitton’s trek. This book published by the maison and Atelier EXB takes readers around the world by sea, rail or air and on land, through 50 true stories from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Adventure seekers lured by modern modes of transport boarded trains, ocean liners, junks, automobiles, half-tracks, Zeppelins, airplanes and spacecraft seeking novel experiences. What those who travelled in style took with them were trunks, suitcases and hat boxes bearing the emblematic LV monogram.

Illustrated with images from Louis Vuitton’s archives, vintage photographs and travel posters, Extraordinary Voyages travels alongside explorers, aristocrats, artists and hedonistic globe-trotters who took off “to escape into a world of dreams that had become reality”, Mattéoli writes. It tells the history of travel and the French brand’s luggage story, from its founding in 1854 by young Louis, who served 17 years as apprentice to master trunk-maker Romain Maréchal.

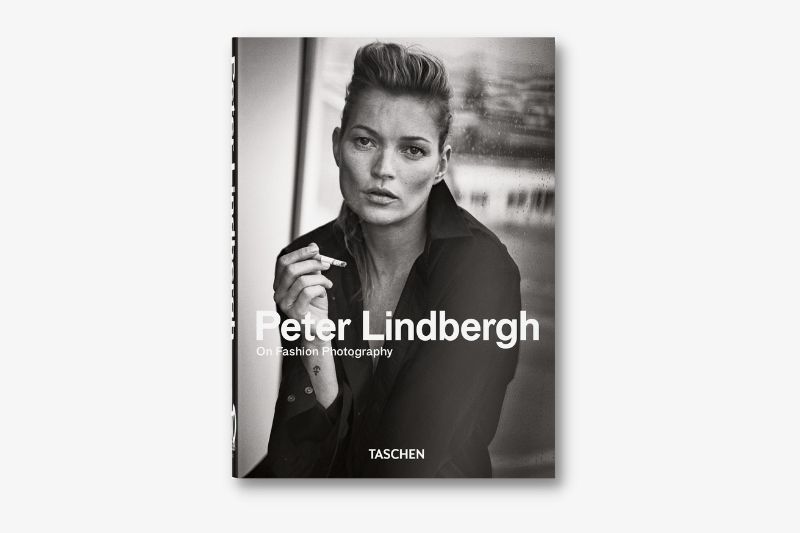

Peter Lindbergh: On Fashion Photography

When Peter Lindbergh (1944-2019) looked through his lens at women, he saw raw beauty enhanced by personality. When he pressed the shutter, he captured real people telling real stories. The German fashion photographer shunned stereotypical images of models, screen stars and celebrities and, instead, portrayed them in natural settings and simple attire and with minimal makeup, breaking the mould of perfect poses weighed down by glitz, big hair and cosmetics.

In this book, he talks about iconic images he shot for various magazines, especially Anna Wintour’s first Vogue America cover in November 1988 featuring Israeli model Michaela Bercu — it broke all the rules and Wintour sensed “the winds of change” — and working with top names in the industry as well as “extremely intelligent women with strong personalities who knew exactly what they wanted. They were also free of social conventions”. He was referring, in online magazine LensCulture, to Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Tatjana Patitz and Christy Turlington, fresh faces he turned into supermodels with his White Shirts series shot on a Malibu beach in 1988.

This special edition of Peter Lindbergh: On Fashion Photography has more than 300 images, many previously unpublished, gathered from his 40-year career and an adapted 2016 Vogue interview on his “big supermodel moment” and individuals who personified the new woman of the Nineties. The man who altered the landscape of fashion photography with audacity exhibited in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Berlin Museum for Contemporary Art, and Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow and various other places.

This article first appeared on Sept 20, 2021 in The Edge Malaysia.