Glashütte is commonly referred to as the cradle of German watchmaking (All photos: A. Lange & Söhne)

Within hours of arriving in the German city of Dresden, I was absolutely in love with it and its fascinating past. The capital city of Saxony has a long history as the royal residence of the electors and kings of this region who, for centuries, furnished it with cultural and artistic splendour. Bombings during World War Two destroyed major parts of the original structures, many of which have been painstakingly restored after the reunification of Germany in 1990. A cultural, political and educational hub for the whole of Europe, Dresden’s rich cityscape is a meld of many architectural styles — predominantly Baroque, with contemporary accents a result of more recent developments.

Dresden is also home to a small village called Glashütte, commonly referred to as the cradle of German watchmaking as it is the birthplace of the nation’s heritage in haute horlogerie. Although sunny in Dresden, it was slightly overcast on the day we arrived in Glashütte, which is nestled comfortably in a bucolic, narrow valley. There are no hotels here, I was told, because there is no space for them and the mayor is not keen on building anything new. It is, quite literally, stuck in time — located along the two roads that snake through Glashütte are several watch manufactures, notably A. Lange & Söhne and independent brands Tutima and Nomos, as well as the Swatch Group-owned Glashütte Original.

I could not help but notice a few similarities between Glashütte and Vallée de Joux, the famous Swiss centre of watchmaking — the sense of isolation is the same, the harshness of the weather (winters in Glashütte can be cruel, apparently) and the same mountainous environment. However, things happened in Germany a good 100 years after they did in Switzerland — it was only in 1845 that Ferdinand Adolph Lange along with Julius Assmann, Adolf Schneider and Moritz Grossmann (the four gentlemen known as the fathers of German watchmaking) laid the foundations of haute horlogerie in Glashütte.

This village flourished with the opening of supply chain businesses that included the manufacture of screws, balances, cases and tools to support the booming watch industry. And seeing how important education and training was, to ensure the continued growth of the trade, the pioneering watchmakers banded together in 1878 to establish the German School of Watchmaking, which today houses a museum managed by the Swatch Group.

While Switzerland escaped the effects of history’s dramatic upheavals, Germany was at the epicentre of it. After World War One came the devastating economic crisis. Then, following World War Two, the communist regime took over in East Germany, orienting watch manufacturing towards other directions in the process. Glashütte gradually rose from the ashes, though, and after the reunification of Germany, Ferdinand’s great-grandson, Walter Lange, with the help of his friends from IWC Schaffhausen, Günter Blümlein and Hannes Pantli, decided to resurrect A. Lange & Söhne and, subsequently, the German watchmaking industry.

In 2012, the company — by then owned by the Richemont Group, with Walter on the board of directors — announced plans for a new manufactory as it had outgrown its existing facilities. Unveiled three years later by German Chancellor Angela Merkel and then Saxony prime minister Stanislaw Tillich, the modern 5,400 sq m complex is a Glashütte landmark that, despite its contemporary architecture, beautifully merges with its tranquil surroundings.

In one of the two new buildings that form the overall complex, a formal foyer provides visitors with a quick history of the respected watchmaker, and the quiet corridors lead to the various departments that piece A. Lange & Söhne watches together. Inside, slightly inclined, large-format atelier windows assure ample lighting at the workstations, and the ultra-modern workshops ensure watchmakers can enjoy virtually dust-free conditions. Exquisite architecture is evident inside as well as outside. The highlight, for me, was a grand staircase that led to the multilevel facility at the centre of the building.

Interestingly, the building is also a testament to sustainable architecture and innovative energy management. Saxony’s largest geothermal energy plant — with 55 downhole heat exchangers extending to a depth of 125m — keeps the indoor climate pleasant throughout the year. Thus, the new Lange manufactory is a CO₂-free facility that contributes to climate change mitigation.

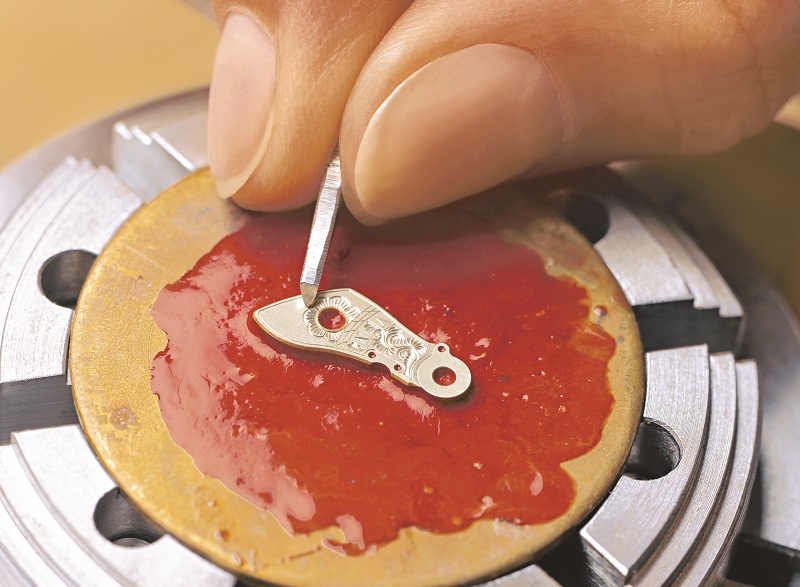

The machines and other equipment used to manufacture movement parts are located in the lower-slung front section of the building, as well as several departments in which small components are manually engraved and decorated. Of note are the craftspeople who engrave the balance cocks that go into every A. Lange & Söhne timepiece. Each engraver has a design exclusive to them, so if you ever take your watch apart, you can trace it back to the person who shined, polished and engraved the balance cock, and say hello personally. You can also personalise your balance cock, although this proviso tends to be reserved for the maison’s more exclusive timepieces.

There are separate departments for engineering and design, prototype production and testing, parts production, finishing and engraving, and first and second assembly. Yes, you read correctly — every single A. Lange & Söhne movement, with its hundreds of individual parts, is assembled by hand, studied and deemed to pass all precision tests, and then taken apart, cleaned, maybe further decorated, engraved or polished and then assembled by hand again to ensure perfection and flawless precision. A detail I found particularly interesting was that a substantial number of the people peering over microscopes, either assembling movements — including a tourbillon — or working on the minute finish, were women.

Around the corner from the manufactory is the original building Ferdinand lived in, which has been restored to serve as a showroom. It was here that we met director of manufacturing Tino Bobe for lunch, and I asked about the women. “This is quite typical of German watchmaking,” the Glashütte native answered matter-of-factly. “In East Germany, women were historically always encouraged to work, unlike in West Germany. And watchmaking calls for the kind of precision skills women are actually very good at. At Lange, we’ve always had a high percentage of women in our workforce.”

We returned to the manufacture after lunch to view the maison’s current crop of timepieces, and tried our hand at engraving a balance cock of our own. At three times the size of the versions used in the watches, this was still an incredibly difficult task. However, the setting we were in was sublime. Looking up from our workspace, the view was of lush green forests that separate Glashütte from the Czech border, and I imagined that this must be quite a nice place to spend the day, even if it is for work. Indeed, it was the impression I got from the warm, friendly way the staff reacted to each other.

“Because we are a small manufacture, it feels like we are all part of an extended family,” Bobe said. “I feel that is one of our strengths — we focus on a limited number of watches that are perfect in every way and, of course, we focus on the team of people who are responsible for these timepieces. This is our strategy, and it is one that has worked very well for us too.”

I have always been a bigger fan of German watchmakers than their Swiss counterparts, so being in Glashütte was truly an eye-opening experience. When I come back — and there is little question of this — I hope to spend more time simply wandering the streets of this charming village, where time stands still and yet ticks through some of the world’s most beautiful watches.

This article first appeared on Mar 11, 2019 in The Edge Malaysia.