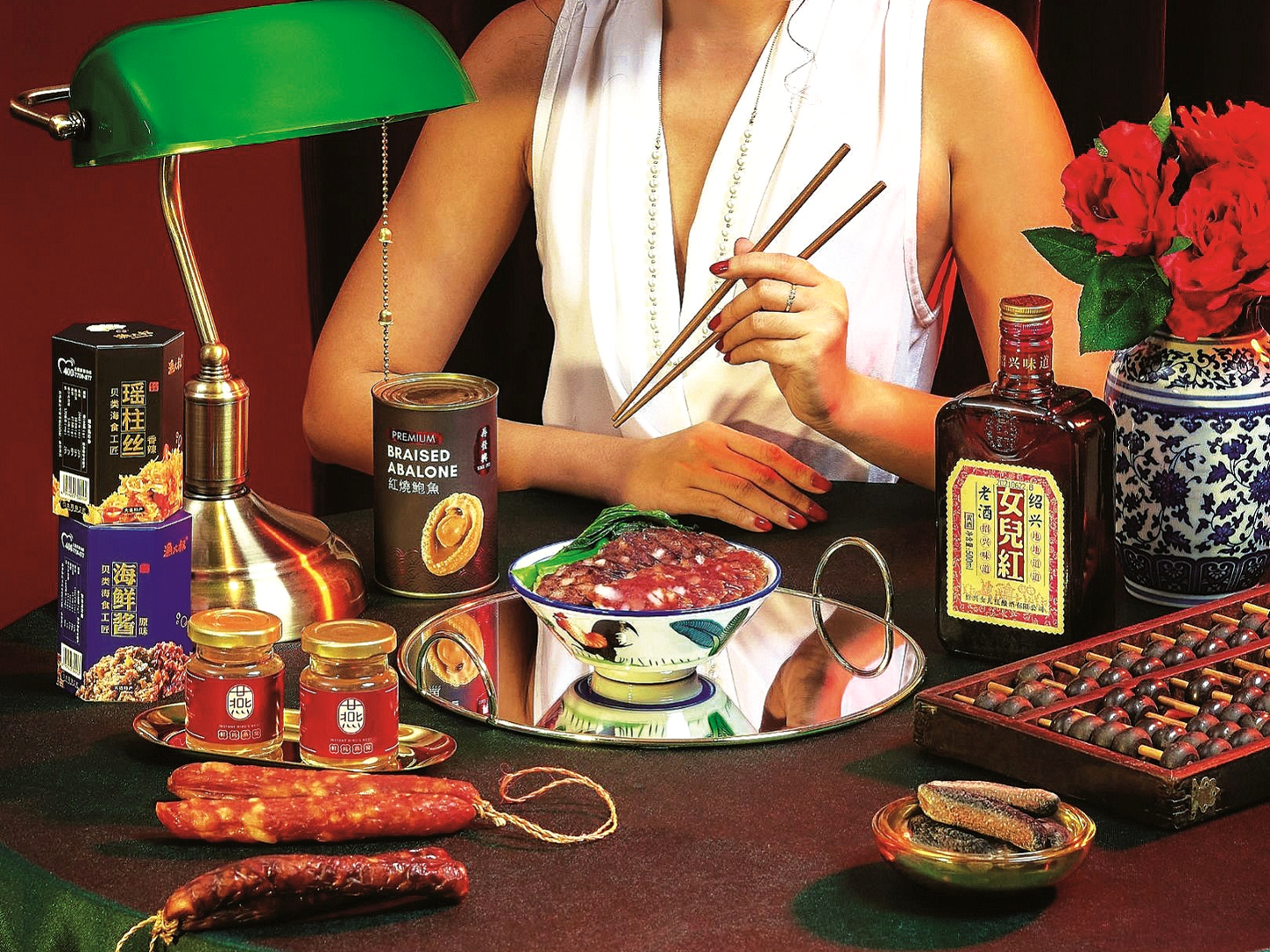

To woo a new audience, Lana Ng put together recipes that make using their various products look easy (All photos: Chai Huat Hin)

Modern families can have their fill of chicken soup for the soul, with its swirl of uplifting words. For those who grew up in typical Asian homes, nothing beats a steaming bowl of dark, aromatic herbal soup, boiled with patience and love by mum, usually, who would have made a trip to the medicinal hall for some of the ingredients needed.

Those brews can be bitter, but the stories of their nourishing properties and long-term benefits — they reduce stress and fatigue, boost the appetite, improve digestion, and balance the yin and yang in mind and body — told repeatedly to make you slurp down every drop, are sweet as they tell of home and family.

Lana Ng remembers being told how she was often sick as a child and prone to fever. “I had to drink a lot of herbal stuff [comprising] ginger and icky black herbs”, ingredients sold in her maternal grandfather’s dried seafood and traditional Oriental grocery store.

Lim Boon Peng had set up Chai Huat Hin (CHH) in 1972 with his partners at Central Market, Kuala Lumpur. A year before he died in 2016, his granddaughter took an interest in the company, wondering how she could bridge the decades-old business with consumers today who, like her, grew up with regular booster bowls of herbal concoctions.

lana_ng_chai_huat_hin.jpg

“I do not want to focus on the health benefits of the herbs and other products. I want to use the fun and quirky elements, something rooted to the past, like what my grandmother tells me you can cook with an ingredient, so it resonates with the younger generation,” Ng says.

E-commerce facilitates that connection, with accessible and relevant marketing and creative content. She uses vibrant shades and attractive packaging to offset the grey or brown herbs, dried seafood and cured meats. Bringing in popping colours can make anchovies look very beautiful in pictures, she adds.

There is more than meets the eye in developing a business where traditions and practices are passed down from one generation to the next through cuisines and delicacies. Every ingredient or dish has a meaning attached to it, and a story. Customers may know what mum used to place in the pot but getting the ingredients can be daunting for the “banana generation”, an anecdotal term for those described as “yellow on the outside but white on the inside”.

“There are lots of us here in Malaysia who are not entirely ‘whitewashed’ and still very Chinese. I want to reach out to them,” says Ng, a banana herself. “I want to cater for the English-educated consumers who grew up in traditional Chinese homes.

“There are many shops online selling traditional herbs but they communicate in Mandarin. We may know what a particular item is called though we can’t read Mandarin. But certain things have different names in different dialects and it’s very intimidating when you want to buy something and cannot connect with the shops.”

chai_huat_hin_shopfront.jpg

The biggest challenge she faced in trying to bridge tradition and modernity was getting acquainted with the stock in CHH. “Going through all the products took quite a while because everything was in Chinese.”

Setting up the company website was a lot of work too. To woo a new audience, she put together recipes that make using their various products look easy. “We simplify as much as we can without compromising on the taste.” Shortcuts, such as pre-mixed condiments for the different vinegars required for chi keok choh (pork trotters in vinegar), allay uncertainty about weights and measures.

Encouraging customers to talk to the team on social media, asking what they plan to cook and recommending specific items was another vital step. When people know they can use a familiar ingredient in cooking, they are inclined to go for it, she notes. Many products can also be used to make drinks, such as goji berry, red dates, ginseng, Mandarin peel and even black fungus.

Going online pre-pandemic proved to be a blessing for CHH because when the coronavirus hit, its website was up and running. “We already knew what to do. Without it, we wouldn’t have been able to sustain our business, what with rental fees and [the salaries of] old uncles who have been working with us most of their lives.”

Covid-19 and the emphasis on eating healthier and cooking at home had its lighter moments. “One thing we found was a lot of people loved their luncheon meat. They were buying it off the shelves, especially during the first MCO (Movement Control Order). We literally ran out.”

Cooking sauces are another bestseller among the young, who seek convenience. If the dish tastes similar to what they know, or like, they are up for the ingredient that makes it happen.

Same-day delivery, promotions and loyalty points are ways through which Ng engages with consumers who prefer to order online, unlike the older generation that likes going into the shop and spending hours taking their pick of fresh herbs packed on the spot for bak kut teh, as well as fermented beancurd, mushrooms, fish sauce, nuts, beans, grains, rice wine, noodles, spices, imported canned food and seasonal festive goods such as waxed duck and sausages.

Perhaps they enjoy chatting with the staff, old-timers who know their stuff. “One uncle is an expert on lap mei (preserved meat) — every year, people just look for him. Another can tell you what you need when it comes to Teochew or Hakka cooking,” says Ng.

The sports science graduate from Toronto, Canada, is thankful her maternal uncle, who took over CHH with his wife and sister after grandpa’s passing, gives her the liberty to do whatever she deems fit.

“When I joined the company in 2018, I told them I’m not in marketing. I just want to try and have fun and see what I can do. They’ve been very open to my ideas. Every time I approach them, my uncle will say, ‘Haiyah, online things I don’t know. You just do lah’.”

Now on a firmer footing, Ng wants to give CHH’s operations a “facelift”. “I will keep the old vibe but at the back end, I want to systemise things, especially for stocktaking.” Which means instead of walking into the storeroom and counting the numbers, staff will be able to check what is running low with a click, and replenish supply. Old set-ups where workers know what is kept where are charming, but “if you want to work and evolve with the younger generation, you need to upgrade as well”.

Traditional delicacies prepared the modern way can help people preserve their culture and history. With that in mind, Ng hopes to bring in gadgets that lend busy cooks a hand, such as a wooden bak chang (Chinese dumpling) mould that enables novices to hold the ingredients together before wrapping and tying up the bundle. She brought back a mould from China, then engaged a local carpenter to make one with the wood oiled and sanded.

Branding is high on the agenda as the company prepares to celebrate its 50th anniversary in October. Ng, the only one from her generation in the family business — there are six others, all of them young — says consumers who see the shop pictures that she posts tell her their grandmothers or mothers used to go there.

“They know of our existence but not our brand name. It’s time to let them know our name: Chai Huat Hin means continuous prosperity in Chinese. I want people to know us as one of the very few traditional oriental grocery stores that are still around, where they can come and look for the ingredients they cannot find in the supermarkets.”

As one who grew up on traditional Chinese herbs, Ng also wants to assure consumers they are not boring stuff or difficult to use. “Yes, some dishes can be tedious to cook. But they are worth the effort if it’s something everyone likes, or if you’ve had it every year, especially during festive occasions.”

This article first appeared on Jan 24, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.