Owner Dr Ahmad Helmi Azhar (Photo: Low Yen Yeing/The Edge Malaysia)

Happy is the man who can have a place of his own to indulge in his passion. Happier still is he when, as his interests expand, so does that space. Meet Dr Ahmad Helmi Azhar, owner of Liberal Latté, which offers good coffee and conversation, along with good books and bites.

Helmi says it repeatedly, in between pauses during a rambling chat: “This is purely passion, that’s why I keep the café like this. You can see by the design it is not commercial. It’s a lepak place and the elements are real.”

The UK graduate, who did electrical and electronics engineering at University College London and his PhD in communications technology at Oxford, is a full-time government relations specialist at Telekom Malaysia. “That’s why I’m a bit reluctant to go public and talk about business. But this is pure passion.”

Liberal Latté started in 2017 as a takeaway coffee bar, a grab-and-go operation with one table for customers to sit a while. In the first year, Helmi struggled to pinpoint his clientele — students from a nearby university campus or workers from the offices around his café, tucked within Wisma E&C in Damansara Heights, Kuala Lumpur.

coffee_and_sandwich.jpeg

“This area is very tough and most cafés here don’t last. The tricky part for us is, in the afternoon, there are lots of food stalls. There’s no point opening at night because this is an office area.

“We thought students would want to come but they might not have the spending power. Even if they did, they might prefer the student lifestyle, which is Starbucks rather than good coffee — spend there, take pictures.”

Once Helmi decided his real market was the working crowd, he spent the second year optimising that segment.

In the UK, he had been part of a team involved in Projek Kalsom, which organised motivational camps for students. After returning to Malaysia, he used Liberal Latte to train volunteers for two English camps that he ran, called Invictus Camp.

But the business was bleeding and its model needed adjusting, he realised. So, when the lot next door became vacant, he took it up and expanded to accommodate an event space and a bookstore. He soon noticed that the bigger area was attracting another group of clients: People liked coming to do their work there. A baby grand by a glass wall with ceiling-high bookshelves behind it and different-sized tables spread across the floor make the café a cosy co-working option.

Eventually, when another adjacent lot became available, Helmi took it up and started TigaBatu, a fine-dining space that offers Malay food inspired by Negeri Sembilan’s Tiga Batu tribe, of which his paternal grandmother is a member.

“I love my grandmother’s food and I want to recreate the traditional dishes so that, when I am old, I can still eat them. I’m a foodie myself,” says the eldest of four siblings.

makan_space_1_dr_azhar_helmi.jpg

TigaBatu’s signature dish is rendang itik, which he cooks himself. Diners can make a general request of what they like and his chef will then curate the menu for them and explain each course as it is served, making the meal a Malay omakase experience. Other food choices can also be prepared at this private space, which seats 30 guests but does not take walk-ins.

People say he has something unique at TigaBatu and ask why he does not market it more. “Not that I don’t want to. But, if by doing so, I lose the boutique part of it, then no. If it sustains itself and serves my purpose of entertaining and preserving the food I like, then I’m happy.

“To do this — the coffee, the books, the food — is a dream come true in many ways,” says Helmi, 35, as he shows us around Liberal Latté, before settling down to tell how it all began.

Oxford is a coffee town with lots of cafés, where Helmi spent a lot on caffeine jolts. In university, friends knew him as the guy who had a coffee machine in his room. “If they wanted to come and do work, they got good coffee — no need to pay.”

dr_azhar_helmi_event_space_2.jpg

When he returned home after eight years abroad, he thought, “Hey, if I spend RM20 a day on coffee, I might as well set up my own shop.”

Helmi makes a mean coffee. “I learnt over time. When you buy the machine, they will come and train you.”

Pointing to the titles on shelves lining the walls of Liberal Latté, he explains that Eirene Bookstore, a separate entity set up with a partner, can be both a library and bookshop. “These are books I aspire to read,” he says, smiling, after pulling out various volumes. “I don’t mind people coming in to read. My aspiration is to have a community space for passion projects.”

But when it comes to selling the books, this self-confessed hoarder is “very reluctant”, more because some of them are no longer in print. He used to have Lat’s cartoon compilations in Chinese, Tamil and Arabic, at Liberal Latté. Unfortunately, his staff, unaware that he did not want to sell them, sold some off when he wasn’t around. “You can’t find them any more,” he laments.

Helmi reads non-fiction in a thematic way. For now, his interest is the history of art in Malaysia, and it loops to how non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which artists have begun to use to trade their works, can democratise art ownership and make it available to more people.

“I’m passionate about art and feel NFTs can give a new breath to the industry. Adoption has to grow organically, and is not about quick money. It is about access to art collection for the younger generation, by means of co-ownership via blockchain.”

He has established Tribuano.io, an NFT platform where physical art works will be fractioned and put up for sale. If a piece costs, say, RM20,000, anyone can buy a fraction of it on the website. When the piece is auctioned off — payment is made in Ethereum — dividends will be paid out according to how many fractions the person has purchased.

Hardly anyone can hope to own, say, a Picasso, Helmi reasons. But fractioning art would give them a chance to do so. It is akin to being the shareholder of a company. Democratising ownership this way gives people a connection to art and will, he hopes, generate fresh excitement in the industry.

“It gives new meaning to art. People like us with no relationships to artists can now say, ‘I know who they are.’” He set up the NFT website recently and hopes to meet artists and invite them to place their creations in Tribuano Gallery.

He plans to start with Fendy Zakri’s works, on display at the café. “I evaluate a piece based on how it changes the mood of the surroundings, and what feelings it evokes in me,” he replies, when asked why he picked the minimalist artist.

Helmi’s personal collection includes a series of paintings by the recently deceased Yusof Gajah — whom he knew personally — which adorns one wall of TigaBatu.

He speaks warmly of the artist known for his colourful elephants. “As he got older, instead of fine illustrations, his work became more abstract. The composition was there but his hand was not precise any more. But I liked [those pieces].”

As a former affiliate to the International Telecommunication Union based in Geneva, Helmi has been involved in study-group discussions on distributed ledger technology, less formally known as Blockchain, since 2015 and is familiar with cryptocurrency. But he never felt the urge to buy it until NFTs came out.

“Then I realised this could possibly be a game changer,” he says.

As an asset class, art is accessible only to those who have money. Using NFTs to bring pieces to those who otherwise could not afford them is an example of employing technology as a tool to drive change: it works faster than most traditional systems.

He cites another example: ride-hailing apps, which have removed the frustration commuters felt whenever taxi drivers overcharged them or would not use meters, or refused to drive to traffic-heavy and flood-prone areas.

Providing an online marketplace that makes art available to more people looks like another passion project Helmi is all set to throw himself into.

“If we can rejuvenate the industry by means of NFTs, it is something we can be proud of.”

Going back to his café, he shares that reopening after the extended lockdowns has not been easy. “There’s a lot of fear and reluctance. Also, the old community has gone. There used to be one — you called someone and he came and you talked. We need to build a new community.”

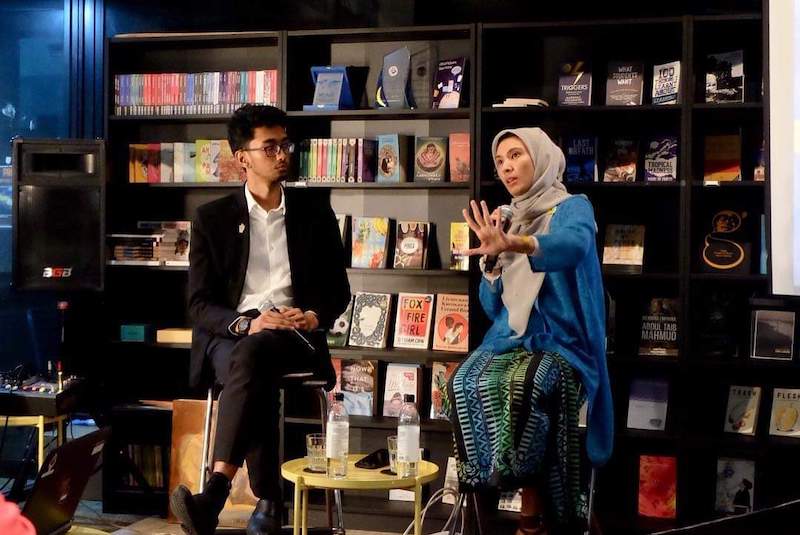

izzah.jpeg

Reintroducing OpenCoffee KL, which is held every second Tuesday of the month at 8am, is one way, says Helmi, for whom working remotely from Liberal Latté was a sweet spot for his career.

“Physically I am here enjoying my coffee in this space, but my thinking and focus were on work.”

Returning to the office means that adjustments are necessary. The timing is right, he thinks, because his setup has grown and is running independently.

This article first appeared on Mar 28, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.