Melvyn Kanny and his wife Jeyamalar Sinniah (All photos: Low Yen Yeing/The Edge Property)

Melvyn Kanny thought his wife was kidding when she asked him to design a ring to set the blue topaz he had bought her in Nepal some years ago. The request, though unwonted, was not unfounded. “You’re a designer,” Jeyamalar Sinniah reminded him.

He is, but of houses, not jewellery. The architect has won awards for bungalow designs that are green, sustainable and relevant in the tropics. Jeya was serious, so he decided to give it a shot.

Kanny bought books on jewellery, signed up for online jewellery design courses and set to it. But the deeper he went into the subject, the more he couldn’t do it. The problem was the gemstone itself, he soon realised. “It has a shape, a design that dictates everything. You can’t do something really different.”

Kanny wanted to design something contemporary and found the stone “a distraction in itself”. So he put it aside, started doing his own stuff and the designs began to flow.

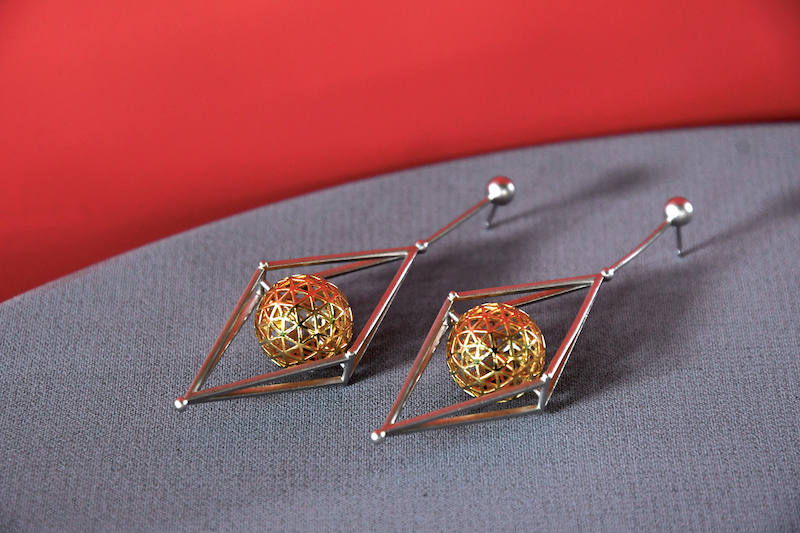

That was the germ that led to the eventual birth of Zikurat, sterling silver jewellery fashioned following the tradition of scale, proportion and spatial simplicity. Geometrical volume and clean, abstract, uncluttered lines give his pieces their signature look — simple elegance, with form meeting function minus distracting exuberance. Thus the tagline, “It’s not all about the carat”.

20220218_peo_jewellery_zikurat_12_lyy.jpg

The brand name is derived from the word “ziggurat”, which means an ancient Mesopotamian temple. The ziggurat was one of the earliest forms of architecture built with function and design in mind, the designer explains. It was also symbolic of human ingenuity, with the progress of the Bronze Age, when jewellery made from gold, silver and other metals were first used.

“What I’m trying to say with our branding is we’re going back to the origins and relooking the redesign of jewellery without influences from commercial trends. We’re going back to basics and starting all over again,” says Kanny.

To him, jewellery is a new baby that took a long time gestating. “It was a struggle,” he recalls. Pre-pandemic, more as a hobby than in earnest, he sketched out ideas on his handphone and developed them in his office, where designers digitised the designs. Just for fun, they made models using cardboard.

With time on his hands during the various iterations of the Movement Control Order (MCO), Kanny soon had 10 designs and began thinking he could get someone to turn them into jewellery. All the local jewellers he approached said they could not do it because his designs looked very slender and fragile and the jewellery might not come out nicely. In Malaysia, jewellers use the traditional casting method: They reproduce pieces with a mould made of rubber or silicon. Or, they are mass-produced in China and then assembled here.

After a long search, he met a guy whose factory in Kuala Lumpur manufactures jewellery for the big players. “He looked at my designs and said, ‘I can make it. We have the equipment but it’s too much trouble’. He wasn’t interested. I was begging him, ‘Do one piece lah’. He produced our first prototypes, then told me I had to find someone else. I guess I was a small fry.”

The guy’s reluctance lay in the challenge of having to use 3D technology to create his delicate accessories. “It was time-consuming — the finer they are, the more difficult to produce,” Kanny says. Also, straight lines are very difficult to create. That is the reason jewellers prefer to do curves.”

Zikurat’s prototypes are created locally. Once done, they are sent to Guangzhou, China, where Kanny has found a company to manufacture his jewellery.

There were teething problems there too. “They used the casting method initially and the pieces came out crooked. I had to teach them how to do it using 3D. We went through the processes and that took about a year.” Discussions on what works best continue even now, which is why one item can take a few months to complete.

During the MCO, Kanny also learnt about social media and online marketing to promote his label. It was launched in December but he has been selling pieces to friends for six months.

20220218_peo_jewellery_zikurat_3_lyy.jpg

“I wanted to focus on a niche market — women professionals who want to look good, especially when attending functions, but not overdress or wear expensive diamonds.

“What we’re trying to say is, maybe you don’t have to go for all the bling. Maybe if you concentrate on a statement piece, you will look even more elegant, more unique. You also don’t have to worry about safety.”

Every Zikurat design starts with a simple idea based on geometrical forms expressing man-made structures, says Kanny, who looks at jewellery from an architectural perspective to bring out the beauty of each piece. The design itself creates its own interesting characteristics, he adds.

The Spiral, designed like a spring, gave him quite a headache, though. “When the manufacturer did it the first time, he thought there had been a mistake. ‘How come this one can bend? Want me to weld it together?’ No, I wanted it to be like that. It’s faceted, with every piece catching the light in a different way so it shines. Because silver is soft, it’s malleable, you can play with it.”

Another reason he chooses to work with silver, an elegant material in itself, is that Zikurat’s pieces — prices range from RM350 to RM450 — are big and would have cost far more if made of gold. Sterling silver, the purest form of the metal, ensures there will be no rusting or discolouration. Some designs have gold-plating highlights that are rust-proof and hypoallergenic.

This year, he plans to expand the brand range — there are 12 designs of rings and earrings now — to bracelets, necklaces, chokers, pendants and chains.

Imitations, reportedly common in China, are not his concern for now. “They have all my designs. If they copy, good for me — it means they can really sell lah. I just want to do what I do and get it out to the market.”

Kanny says he never imagined doing jewellery but the process is not very different from building a physical structure. “The principles and disciplines are very similar: understanding the material and what it can or can’t do is very important. You design based on those perimeters. Also, the proportion and scale.”

Has designing jewellery for women changed him in any way?

“He’s probably looking at women more now … and he’s very critical,” Jeya quips.

20220218_peo_jewellery_zikurat_10_lyy.jpg

“I’m more conscious of what they’re wearing, and I’m thinking, ‘That one is nice. Maybe I should do something based on it’.” Lest anyone gets the wrong idea, Kanny is only checking out their jewellery. “I’m definitely much more aware of fashion and trying to understand trends.”

Styles are moving in new directions, with designers using recycled materials and different colours. Jewellery is not only about precious materials like gold, silver and diamonds now. But he does not plan to follow the crowd because “I want to keep my designs timeless”.

As for Jeya, gemstones still have a place in her heart. “My love for them won’t change just because he is doing jewellery.”

Well, the man who bought the blue topaz at the Everest Base Camp gets the last word. “After I started designing, I forgot about the topaz. One day, my wife came back and was wearing it as a pendant. When I heard how much she’d paid for it, I thought, ‘Oh, I’d really better start doing it’.”

Zikurat is among the brands exhibiting at 'Recrafting Stories: A Decolonial Pursuit', at Small Shifting Space (141, Jalan Petaling, KL) until March 20. Organised by Dia Guild, the show aims to honour the “decolonial journeys” of artists and designers from Southeast Asia, in the context of craft-artisanship, music and literature. See here for more.

This article first appeared on Mar 14, 2022 in The Edge Malaysia.